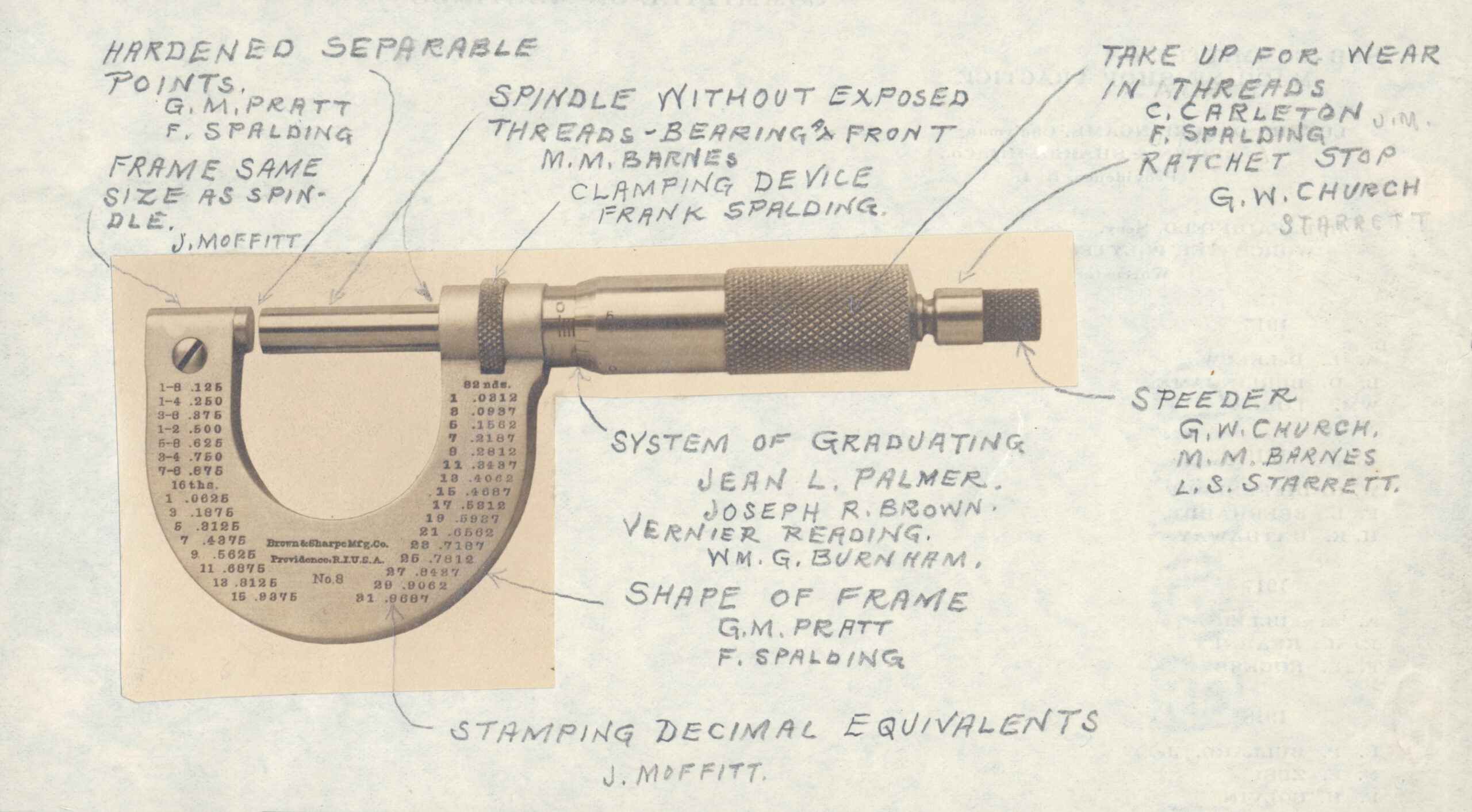

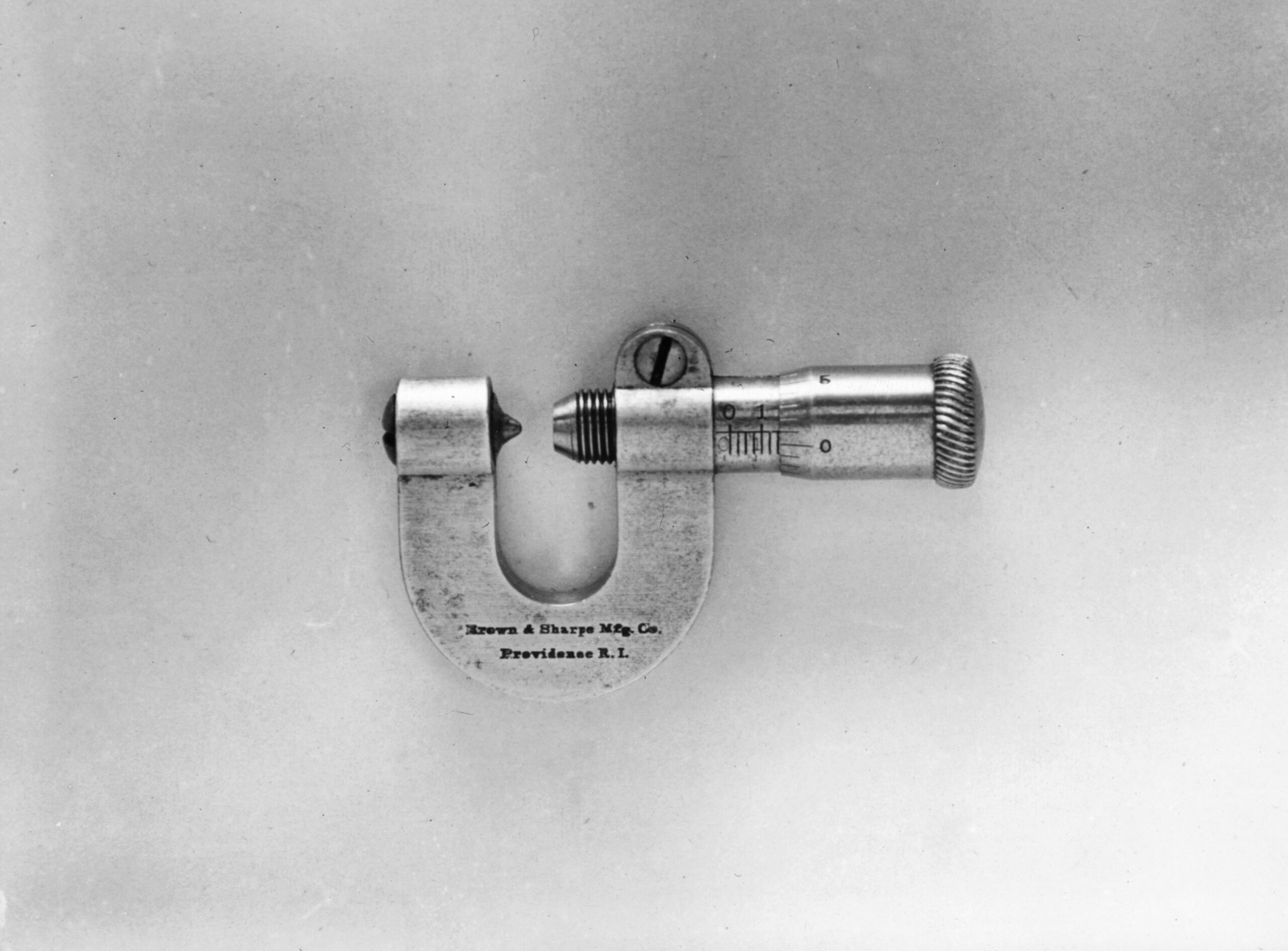

Micrometer

The tool in this image is called a micrometer and was one of Brown & Sharpe’s first machine tools. A micrometer can precisely measure the size and thickness of a piece of metal that then could be used to make a product, like a hammer or sewing machine. The image is a photo of micrometer pasted on a piece of paper with contributor information written in in pencil.

Brown & Sharpe: A Window Into American Industrial History

Essay by Samantha Hunter, Education Outreach Manager at RIHS with Talya Houseman, PhD Candidate in the Department of History at Brown University

The Brown & Sharpe Company is an excellent example of the prosperous history of industry in Rhode Island, spanning from the 1800s to today. Generally, when we think of companies that make products in factories, we assume that they are making final products—hammers, car frames, refrigerators. But, Brown & Sharpe didn’t specialize in making products; they made machine tools that made it easier to then make “looms, sewing machines, locomotives, automobiles, and weapons that made America modern.”1Steven Lubar, Introduction to Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry: Making the Precision Machine Tools That Enabled Manufacturing, 1833-2001, by Gerald M. Carbone with the Rhode Island Historical Society (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2017), 2. For example, one of Brown & Sharpe’s signature tools is a micrometer. A micrometer can precisely measure the size and thickness of a piece of metal that then could be used to make a product.2 Lubar, Introduction to Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 1. How did Brown & Sharpe get into the machine tool business?

Founder Joseph Brown owned a small workshop in Providence where he and his workers specialized in metal work, repairing household items, polishing silverware, and building tower clocks, among other odd jobs. And yet, Brown was focused on creating a machine that could make rulers easily here in the United States. At this point in time—the 1830s and 1840s—if an American wanted a ruler, they “had to import one from Europe or hire someone capable of painstakingly inscribing one by hand.”3Gerald M. Carbone with the Rhode Island Historical Society, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry: Making the Precision Machine Tools That Enabled Manufacturing, 1833-2001 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2017), 9. This desire to build tools that made it easier to produce goods is the inspiration that propelled Brown & Sharpe to the forefront of American industry.

By the time Joseph Brown partnered with fellow Rhode Islander Lucian Sharpe in 1853, the Brown & Sharpe Company had a quality line of products. However, their biggest project did not come until 1858.4Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 14 and 24. In 1858, the company was approached by two men, Wilcox and Gibbs, who were interested in making sewing machines and wanted Brown & Sharpe to make the parts. The sewing machine business was a huge success—particularly during wartime years when uniforms needed to be made—until the company stopped making them in the 1950s. Wartime environments not only boosted the sale of tools to make sewing machines, but also increased demand for Brown & Sharpe’s tools used to make more guns at a quicker rate.5Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 29.

In the years following the Civil War, Brown & Sharpe expanded their portfolios to include machines that better ground metal and tools for Railway construction. The increased production and manpower needed to make it happen forced the company to build a new factory that housed all of its products.6Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 53. The increase in workforce, products, and revenue signaled big success for the company.

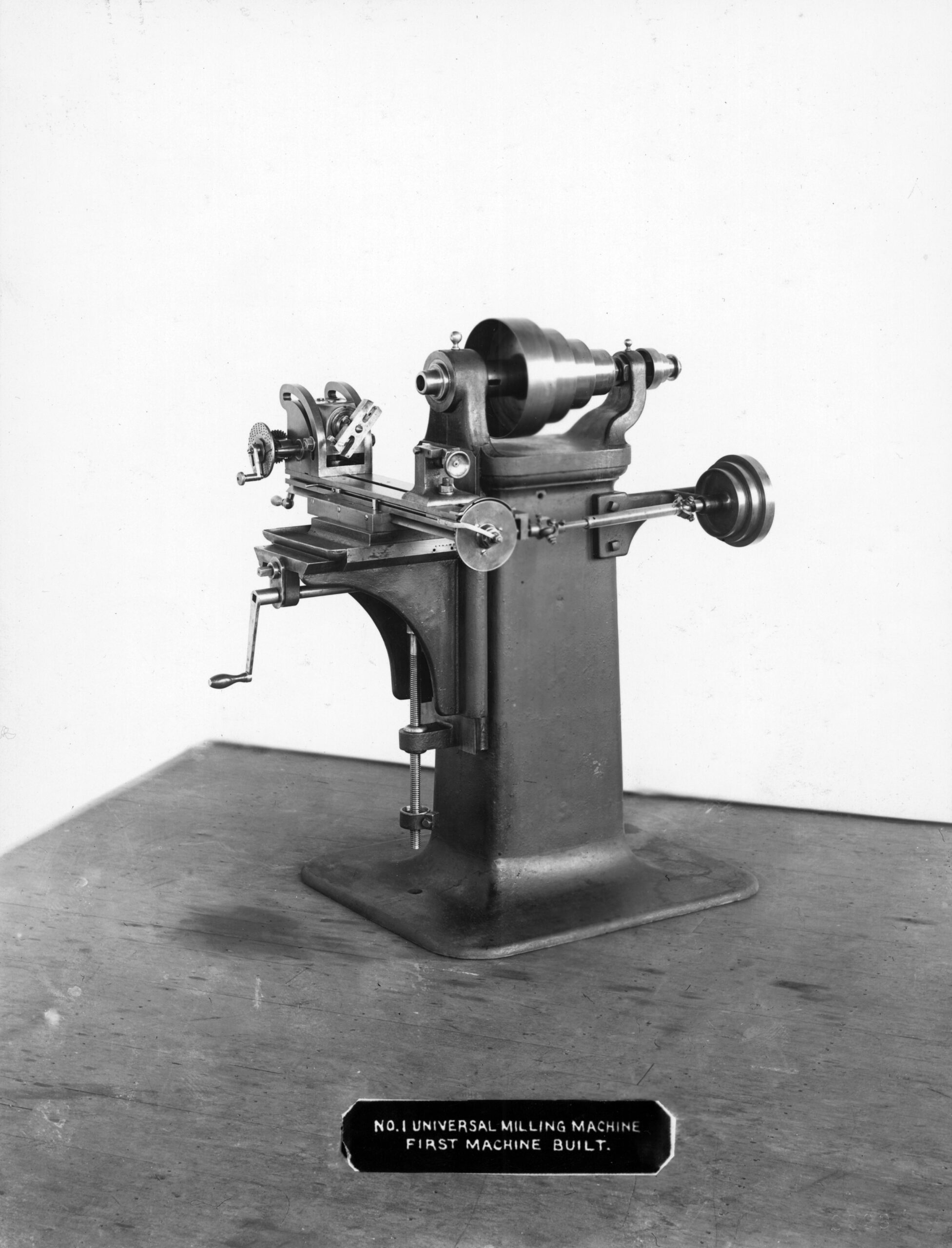

As the 19th century came to a close and the 20th century began, Americans became fascinated with transportation like railroads, bicycles, and automobiles. Brown & Sharpe evolved with the times, creating a Universal Grinding Machine, which was an improved version of their earlier grinding machines, that could grind large quantities of metal and utilized new compositions of steel made with other alloys (a metal made by combining two different kinds of metallic elements, usually to improve its quality or strength) in addition to a Universal Milling Machine which allowed for more efficient cutting of metal.7Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 63. And yet, though their technologies and products evolved with the times, their strategies for the management of workers and working conditions did not.

Brown & Sharpe was in the business of setting wages without input from workers’ unions.8Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 99. However, wages were not the concern of a large strike, which included Brown & Sharpe workers, in 1915. While World War I raged in Europe, orders were piling up for Brown & Sharpe machine tools—more orders equaled more workers needed to fill them. While the demand for tools increased, workers went on strike for an 8-hour work day as opposed to the 10-hour days they were presently working. Executives from Brown & Sharpe did not sympathize with these demands.9Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 118-19. However, due to little financial support available from the union, many workers eventually returned to work though the strike never officially ended.10Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 120.

While the company’s relationship with workers began to change, so did the company’s leadership. By the turn of the 20th century, Joseph Brown was dead, and Lucian Sharpe was very ill. Sharpe named his eldest son, Lucian Sharpe Jr., his successor, though due to some health issues, Sharpe Sr.’s younger son, Henry, took over the company shortly afterward.11Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 104.

World War I increased production dramatically, but as more and more men enlisted and were sent overseas, Brown & Sharpe had a shortage of workers. To fix this, they began employing women in 1918.12Before 1918, women had worked in clerical positions at the company but did not begin working on the floor as riveters, assemblers, screw machine operators, gear cutters, etc. until 1918. 12Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 129. Thriving production rates continued into the 1920s, and the increased work put workers in more advantageous positions to negotiate their benefits. Though Brown & Sharpe was often tough when negotiating with unions and workers, they did offer the option for employees to invest their money into insurance plans that would provide income in old age, and they managed a Relief Association that paid sick and death benefits.13Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 141.

Unfortunately, this success quickly plummeted following the stock market crash of 1929 and continued to decline through the 1930s. Yet in the 1940s, as before, a world war provided an opportunity for Brown & Sharpe to get regain their footing. During WWII, factories that made planes, tanks, and munitions consumed the entire production of Brown & Sharpe’s machine tools and precision instruments. Then, during the Korean War, a small contract with the US government for a top-secret project making gear cases for radio-controlled anti-aircraft guns ballooned into a large contract.14Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry: 184. While Brown & Sharpe didn’t make weapons themselves, their tools were the most efficient to make weapons, and so, in times of war, the government depended heavily on Brown & Sharpe’s ability to make tools.

Wartime production was not the center of success for Brown & Sharpe in the 1950s however; screw machine production was the star. Henry Sharpe Jr. (founder Lucian Sharpe’s grandson) took over the company and predicted that “by 1958, Brown & Sharpe would halve the manufacturing time of a screw machine.”15Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 196. Screw machines made cylindrical parts used in a variety of items like clocks, guns, sewing machines, valves, typewriters, and motors, to name a few.16Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 194. The continued success of Brown & Sharpe led Henry Jr. to reorganize the company into four distinct groups: Machine Tools, Industrial Products, Cutting Tools, and Hydraulics. At the Chicago Machine Tool Exposition in 1960, Brown & Sharpe showcased some of their newest products, including a new grinding machine that could grind missile parts to within 30-millionths-of-an-inch.17Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 202.

All of this advancement meant that, once again, Brown & Sharpe needed a new factory with more space. In 1963, the company announced plans to move to North Kingstown and revealed that for the first time since its founding, Brown & Sharpe would no longer have a presence in Providence.18Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 204. History repeated itself once more in the 1960s, with demand for machine tools on the rise due to the war in Vietnam.19Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 208.

Brown & Sharpe experienced a relatively uneventful yet still productive period through the 1970s, and in the 1980s, Henry Jr. had to consider who would take his place running the company. His eldest son, Henry III, was an option, as he loved to tinker with parts and would go on to be a successful founder of a product design firm but Brown & Sharpe had evolved into a very complex organization, and Henry Jr. concluded that his eldest would not enjoy the administrative work of running his family’s company. So, it was decided that the first CEO of the company outside of the Sharpe family would be a man named Donald Roach.20Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 227. Roach did not last long, though; in 1990, he was fired due to unprofessional interactions with other Brown & Sharpe employees.21Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 244. Roach’s successor was Dr. Frederick Stuber, a director at one of the company’s foreign locations in Switzerland.22Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 245.

At this point, the company was manufacturing parts used by Toyota, Ford, and GM.23Ibid. The early 1990s saw a drop in the global economy, and Brown & Sharpe felt the effects; many workers were laid off, and Stuber announced that “Brown & Sharpe was quitting the machine tool business.”24Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 246. With the appointment of a new Chief Financial Officer to help Stuber, things steadied but never enough to regain the triumph that Brown & Sharpe had once experienced. By 2000, the company had many problems “brought on by poor sales, exchange rate problems, investments…in new technologies…and restructuring charges.”25Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 252. Brown & Sharpe’s Board of Directors decided that they would sell the company to Hexagon A.B., a metrology company in Stockholm, Sweden. The sale was made final when, in April of 2001, Henry Sharpe Jr. and other stockholders voted to approve the sale.26Ibid.

This story of industry and production that ebbs and flows based on national and international events is representative of many companies’ stories. The struggles and successes with technological advances, money, space, working conditions, and unions are what make Brown & Sharpe the perfect window into the history of American industry. Brown & Sharpe’s history mirrors America’s and yet still offers unique insights into local Rhode Island history, too.

Terms:

Micrometer: a gauge that measures small distances or thicknesses between its two faces, one of which can be moved away from or toward the other by turning a screw with a fine thread

Alloy: a metal made by combining two different kinds of metallic elements, usually to improve its quality or strength

Screw Machine: a machine that makes cylindrical parts used in a variety of items like clocks, guns, sewing machines, valves, typewriters, motors, and other similar products

Metrology: the scientific study of measurement

Questions:

What do you think is the benefit of making machine tools instead of final products? If you started your own company, would you rather make machine tools or final products? Why?

Do you think Brown & Sharpe could have made different decisions that would have allowed them to stay open and productive in the 21st century? What would those decisions be?

- 1Steven Lubar, Introduction to Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry: Making the Precision Machine Tools That Enabled Manufacturing, 1833-2001, by Gerald M. Carbone with the Rhode Island Historical Society (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2017), 2.

- 2Lubar, Introduction to Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 1.

- 3Gerald M. Carbone with the Rhode Island Historical Society, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry: Making the Precision Machine Tools That Enabled Manufacturing, 1833-2001 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2017), 9.

- 4Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 14 and 24.

- 5Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 29.

- 6Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 53.

- 7Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 63.

- 8Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 99.

- 9Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 118-19.

- 10Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 120.

- 11Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 104.

- 12Before 1918, women had worked in clerical positions at the company but did not begin working on the floor as riveters, assemblers, screw machine operators, gear cutters, etc. until 1918. 12Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 129.

- 13Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 141.

- 14Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry: 184.

- 15Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 196.

- 16Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 194.

- 17Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 202.

- 18Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 204.

- 19Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 208.

- 20Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 227.

- 21Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 244.

- 22Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 245.

- 23Ibid.

- 24Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 246.

- 25Carbone, Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry, 252.

- 26Ibid.