Rhode Island and the Civil War

Essay by Fred Zilian, Ph.D., Adjunct Professor, Salve Regina University

with additions by Eytan Goldstein, Student at Barrington High School and Rhode Island Historical Society intern

In the 1850s, Rhode Island, like many states in the North as well as the South, hoped to avoid conflict. According to William McLoughlin, “even after southern states began to secede, Rhode Island demonstrated considerable sympathy for them,” sending five delegates to the Virginia Peace Convention in November 1860. In addition, to appease the South (because of its economic relationships with cotton planters), the state repealed the “personal liberty” law it had previously passed to resist the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.1William G. McCloughlin, Rhode Island, A History. NY: W.W. Norton, 1978 In 1860, the choice for Governor was between Seth Padleford (who was a strong anti-slavery supporter) and William Sprague (the conservative choice, softer on slavery, and the heir to a cotton textile empire). Sprague won by just over 2,000 votes.2Patrick T. Conley, An Album of Rhode Island History, 1636-1986. RI Publications Society, 1986

However, when Confederate forces started shelling Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861, Rhode Island took its stand against the South and rose to arms. Eleven Southern states seceded from the Union after the election of Abraham Lincoln, a Republican opposed to the expansion of slavery. Although fighting continued until the end of May 1865, the war was essentially over when General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9.3See map of American Civil War battle sites [link]

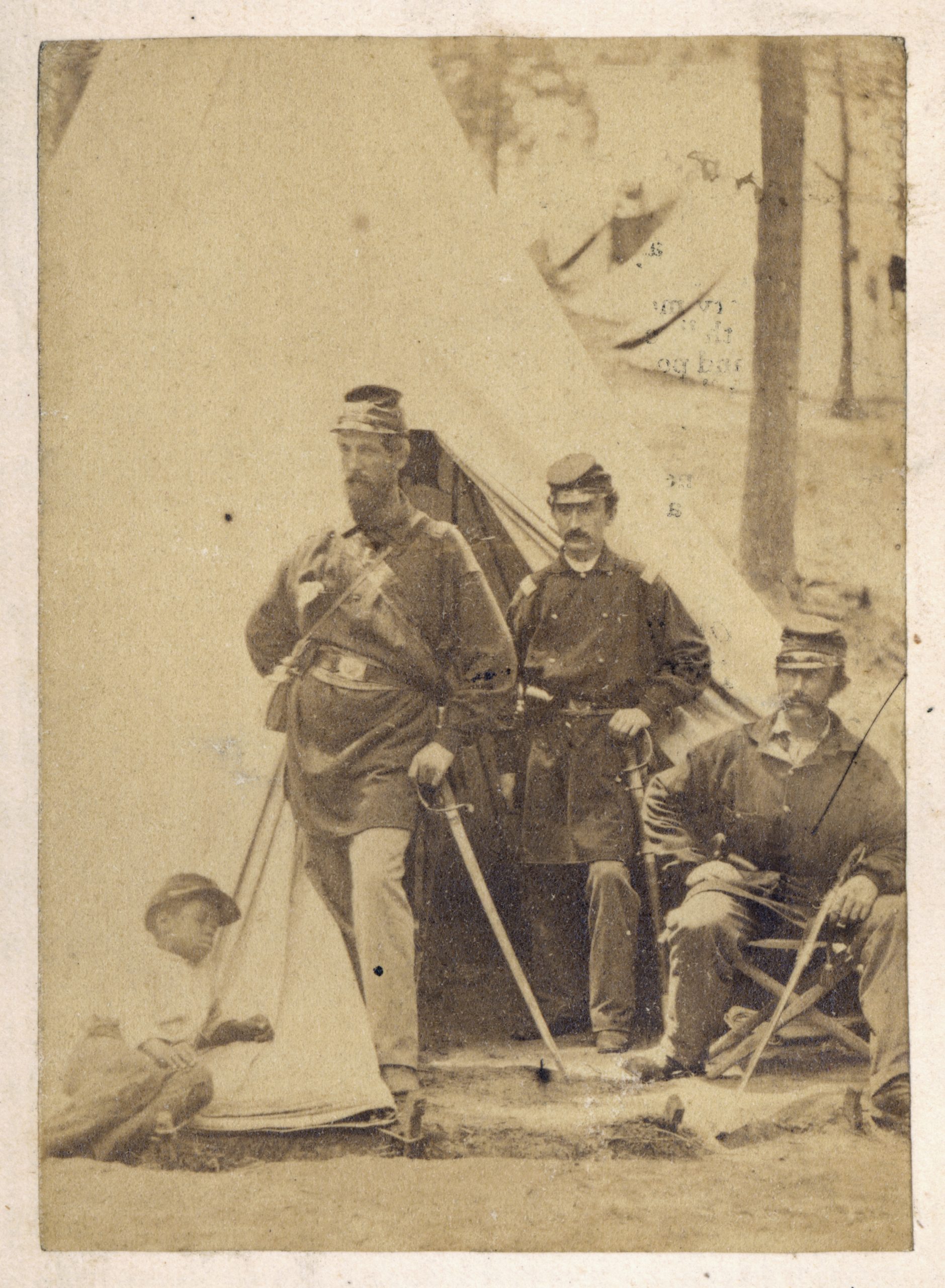

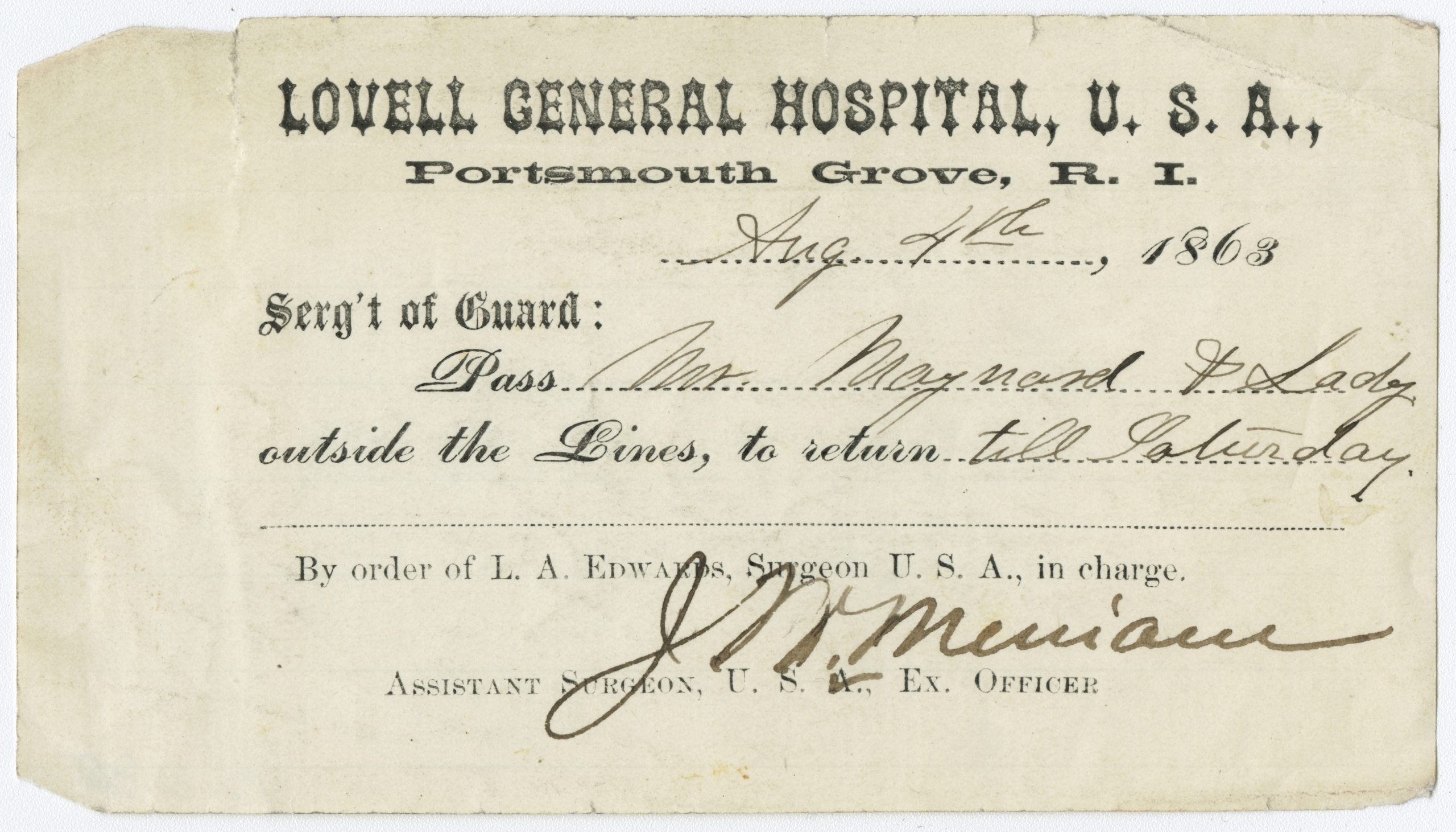

Having banned slavery and the slave trade decades before, Rhode Island was one of the first states to respond to Lincoln’s call for volunteers and to mobilize troops to support the Union. Rhode Island units took part in every major battle of the war, from First Bull Run to Appomattox. Rhode Island factories also provided significant logistical support by producing uniforms, swords, and arms. In addition, Portsmouth Grove Military Hospital in Portsmouth cared for over 10,000 patients during the war. Thousands of Rhode Islanders contributed to the war effort, both on the home front in factories and hospitals, as well as fighting on the front lines.

Lovell Hospital Pass

Learn about the Portsmouth Grove Military Hospital Here

Rhode Island Mobilizes

On April 12, 1861, after the South’s bombardment of Fort Sumter in South Carolina, President Abraham Lincoln issued a call to arms and established Rhode Island’s quota at 780 men. In response, 31-year-old Governor William Sprague, nicknamed the “boy governor,” called the Rhode Island General Assembly into a special session on April 17. Both Houses quickly passed a unanimous resolution to meet the quota. Acts reviving the charters of several military units were approved, activating the Providence Horse Guards, the Narragansett Guards, the City Guards of Providence, and the Wickford Pioneers.

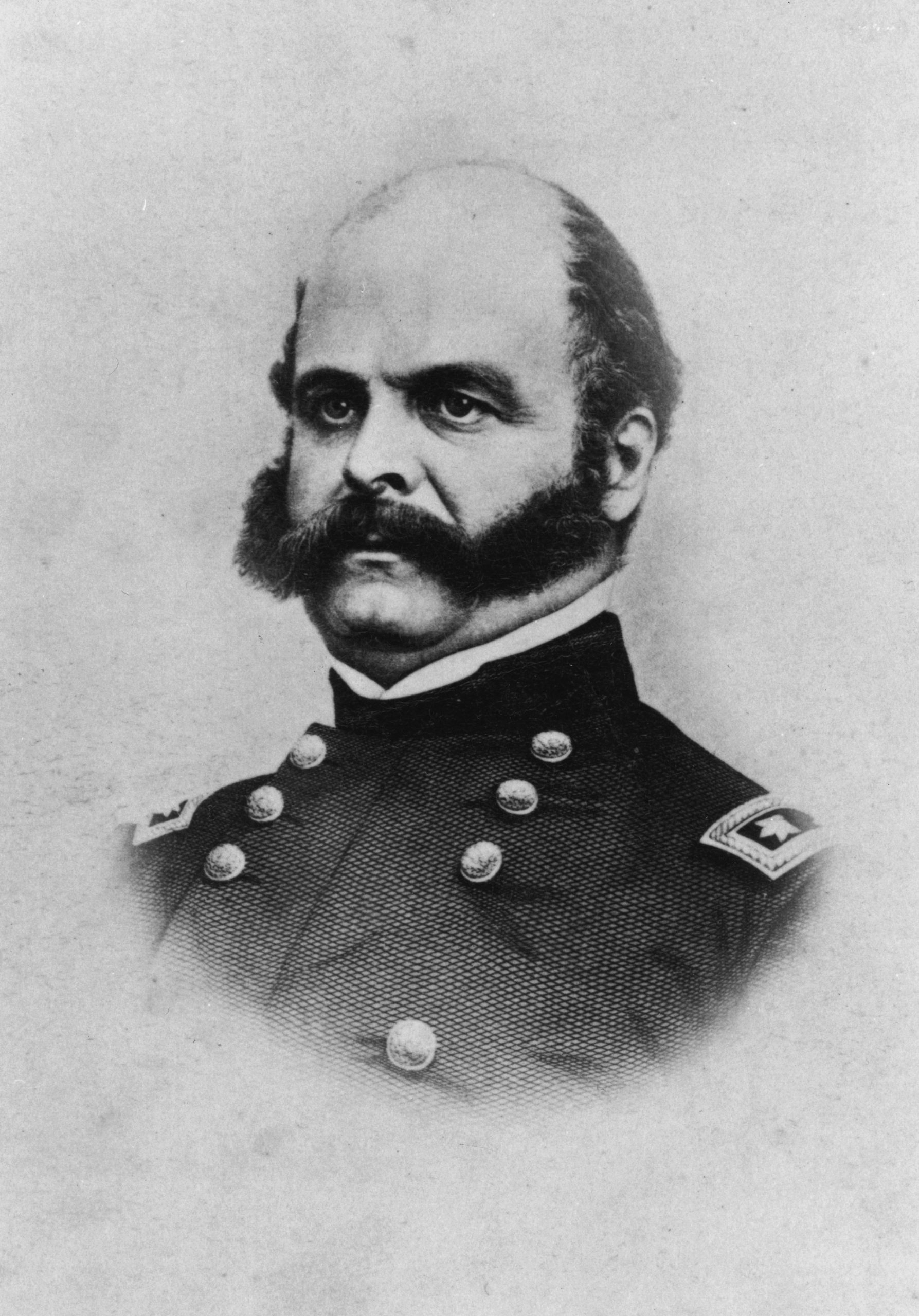

Between April 18 and April 24, 1861, Rhode Island sent its first units off to war. On April 18, a battery of light artillery of the Providence Marine Corps Artillery left Providence. It claimed to be the first organized unit to respond to the President’s call. Following this unit were two detachments, composing the First Regiment, Rhode Island Detached Militia, commanded by Colonel Ambrose E. Burnside, soon to become Rhode Island’s best-known military leader. Ten companies made up the regiment, six from Providence and one each from Pawtucket, Woonsocket, Westerly, and Newport.4Rhode Island Civil War Centennial Commission. Rhode Island Civil War Chronicles: A Presentation of Articles and Photos Recalling Rhode Island’s Participation in the Civil War, 1861-1865, 1960, 5-6; Robert Grandchamp, Rhode Island and the Civil War: Voices from the Ocean State, (Charleston: The History Press, 2012), 19-25 These troops were just the first of many Rhode Island units that would be dispatched to crush the rebellion of the southern states.

On April 20, 1861, the first contingent of 530 men under Burnside’s command set out on the steamer Empire State. The second contingent, comprising 510 men and commanded by Colonel Joseph T. Pitman, departed Providence by steamer on April 24. As they marched to the Fox Point pier, they sang their regimental song:

“The gallant young men of Rhode Island

Are marching in haste to the wars.

Full girded for strife, they are hazarding life

In defense of our banner and stars.”5Mathias P. Harpin, The High Road to Zion (Harpin’s American Heritage Foundation, 1976), 148

Like many Northerners, these men likely believed that the Union Army would defeat the Rebels quickly, allowing their quick return home. But history unfolded quite differently. On May 2, the entire regiment was paraded in Washington, DC, in front of many spectators, including Governor Sprague and President Lincoln. It then marched to the Capitol, where it was mustered into service for a term of three months. Each soldier recited the following oath of allegiance:

“I ___________, do solemnly swear, that I will bear true allegiance to the United States of America and that I will serve honestly and faithfully against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever, and observe and obey the orders of the President of the United States, and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to the rules and regulations for the government of the armies of the United States.”6Rhode Island Civil War Chronicles, 11

Various Contributions to the War Effort

Altogether, the federal government called for troops eight times during the war. Each time, Rhode Island sent more than required. The war, which began to drag on for much longer than most Northerners expected, was the bloodiest in American history, and thus many more troops were continually needed. Rhode Island’s overall quota was 18,898 soldiers, yet it supplied 23,236, proportionately more than any other state. About 2,000 died of wounds or disease. Twenty earned the highest military award for bravery, the Medal of Honor.7Frank J. Williams, foreword to Rhode Island and the Civil War: Voices from the Ocean State., Robert Grandchamp, (Charleston: The History Press, 2012), 12, Appendix I

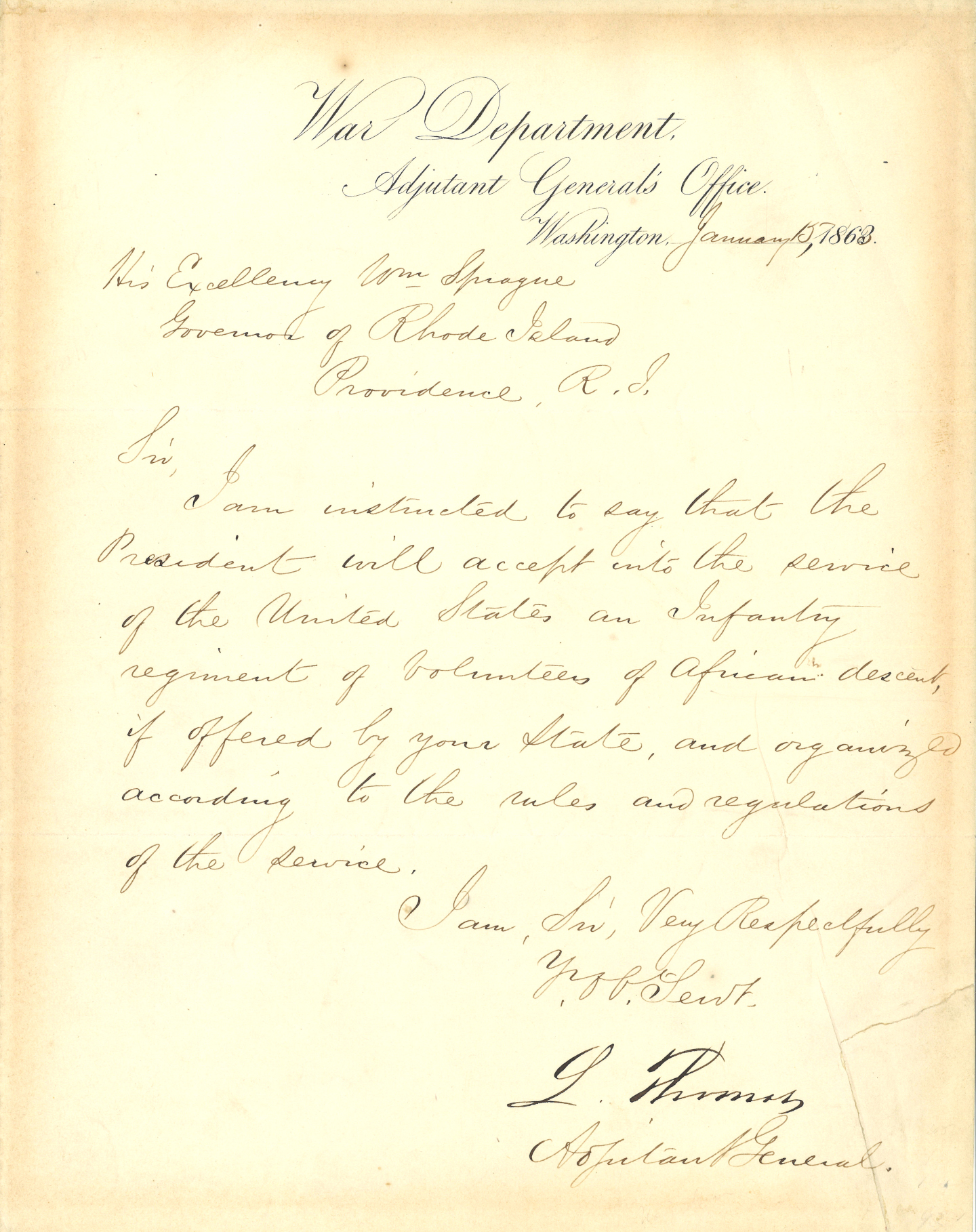

Letter to Governor William Sprague to Accept Volunteers of African Descent

Learn about the 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) unit here

As combat troops, the state sent a total of eight infantry regiments, four artillery regiments, and three cavalry regiments, along with several smaller units. These units fought in every major engagement of the war.8Williams, 12 Rhode Island formed a unit made of African-American soldiers: the Fourteenth RI Heavy Artillery (Colored). At this time, such units were segregated, meaning they had no White soldiers except for the White officers who led them. This unit did not see combat but served duty in both Texas and Louisiana.9Williams, 109-113 They also suffered the highest number of deaths, almost all due to disease, than other Rhode Island units in the War. Despite the racism that prevailed in this period, about 200,000 African Americans served in the Union Army and Navy, especially after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863.

Rhode Islanders did not only send combat troops. The USS Rhode Island, a side-wheeled steamer commissioned in 1861, intercepted Southern blockade runners in the Caribbean.10Williams, 109-113 Many Rhode Islanders served in the Union Navy, including William Taylor, who, as Fleet Captain of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, saw action at Charleston.11“Rear Admiral William Rogers Taylor, USN, (1811-1889)“ Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed 14 April 2020 [link]

In applying its great advantage in warships, Union naval leaders pursued the so-called Anaconda Plan. This strategy aimed to strangle the South’s maritime trade, depriving the Confederate economy of revenue, thus helping the Union secure victory. In Portsmouth, the Portsmouth Grove Military Hospital, established on July 6, 1862, ultimately cared for 10,593 patients during the war.12Frank L. Grzyb, Rhode Island’s Civil War Hospital: Life and Death at Portsmouth Grove, 1862-1865 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2012) The US Naval Academy was relocated from Annapolis, Maryland, to Newport, for security reasons, and remained there until the war ended.13Rhode Island Civil War Centennial Commission. Rhode Island Civil War Chronicles; Frank L. Grzyb, Hidden History of Rhode Island and the Civil War, (Charleston: History Press, 2013), 34-37

Rhode Island also played a significant role on the home front. The A & W Sprague textile factory in Providence (the Governor’s family business) provided the cloth for uniforms. Mills in the Rhode Island villages of Ashland, Carolina, and Rockland produced thousands of uniforms, overcoats, and blankets. In the village of Forrestdale, the local scythe works began making swords, while the Providence Tool Company and the Burnside Rifle Company produced thousands of arms. The Builders Iron Foundry in Warwick manufactured cannons, and the Providence Steam Engine Company built engines for two Union warships.14Maury Klein, “Rhode Island’s Civil War Economy,” in The Rhode Island Home Front in the Civil War Era, eds. Frank J. Williams and Patrick T. Conley (Nashua, NH: Taos Press, 2013), 55-77 Indeed, because the Industrial Revolution had come early to Rhode Island, the state had a well-established manufacturing base and consequently was well positioned to make large manufacturing contributions to the Union war effort. One major advantage that the North had in the Civil War was its industrial economy, and in Rhode Island the many factories were part of that Northern advantage.

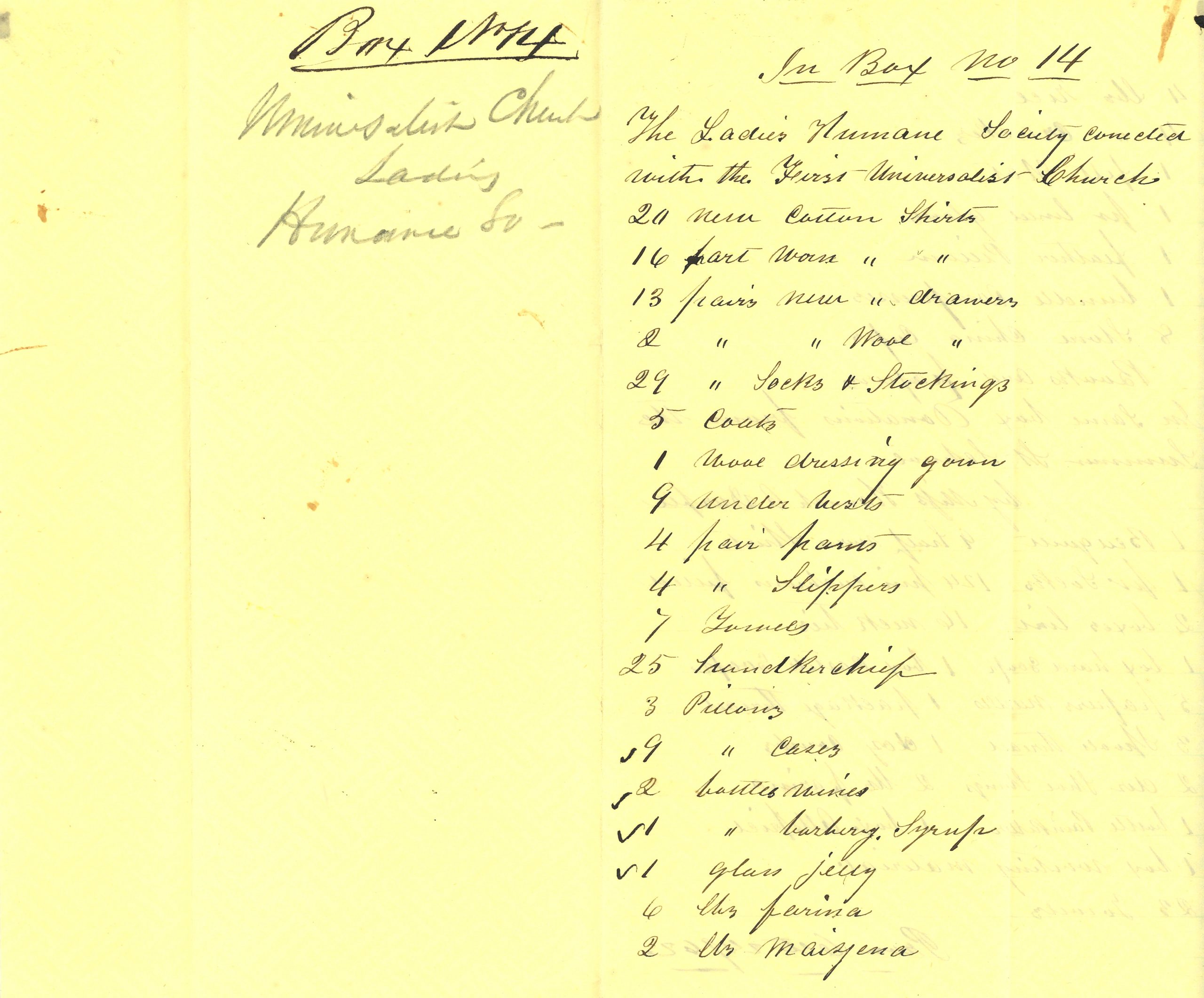

Women also supported the war effort in various ways on the home front. A notable example was Newporter Katharine (also spelled Katherine in the archives) Prescott Wormeley, who had founded the Girls Industrial School in Newport before the Civil War. During the war, she served as one of the first women to assist the Medical Bureau and Sanitary Commission in caring for sick and wounded soldiers. She also became the “Lady Superintendent” of Portsmouth Grove Military Hospital. In her book, The Other Side of War with the Army of the Potomac, she describes the origins, duties, and early work of the newly-formed United States Sanitary Commission. “It was the outgrowth of a demand made by the women of the country” because both men and women wanted to contribute to the war effort. “As the men mustered for the battlefield, so the women mustered in churches, schoolhouses, and parlors….”15Katharine Prescott Wormeley, The Other Side of War with the Army of the Potomac: Letters from the Headquarters of the United States Sanitary Commission during the Peninsular Warm 1862 (Boston: Tickner and Co., 1889), 5 The extreme violence of the Civil War made service in wartime hospitals a grim, but essential task. Disease and wounds killed many soldiers, creating conditions that required positively heroic service.

An Account of Women’s Donations to the War

Read about women's contributions to the War effort here

Rhode Island women also led the moral and patriotic struggle. Late in 1861, Julia Ward Howe wrote her famous poem “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” which, once put to music, became the unofficial anthem for the North. Howe was a talented poet, writer, playwright, preacher, lecturer, and reform leader. She spent much of her life at her “Oak Glen” country home in Portsmouth, Rhode Island. In 1861, she traveled to Washington, DC, met President Abraham Lincoln, and visited military camps in the area. During these visits, she heard a tune popular at the time, “John Brown’s Body,”16This song refers to John Brown, the abolitionist of Harper’s Ferry, VA fame, not to John Brown of Rhode Island celebrating his martyrdom for the anti-slavery cause. As she lay in her hotel bed early one morning, the words for the poem came to her. The poem was first published in the Atlantic Monthly magazine in February 1862 and was put to the tune of “John Brown’s Body.”17“Master of Vineyard Calls Woman Patriot,” Record-Herald, October 18, 1910; “Julia Ward Howe,” accessed May 21, 2019 [link] The women of Rhode Island certainly contributed much to the Civil War effort, foreshadowing the important role they would play in the World Wars.

Notable Rhode Islanders Fight the War

Today, Elisha Hunt Rhodes is a notable Rhode Islander of the Civil War, thanks to his Civil War diary, “All for the Union,” published in 1985 by his great-grandson, Robert Hunt Rhodes, and featured in Ken Burns’ nine-part PBS series, “The Civil War” (1990). The first entry was written in May 1861, shortly after the war began, and the diary closes with an entry dated July 28, 1865. As a member of the 2nd Rhode Island Volunteer Regiment, he fought in all the major battles waged by the Army of the Potomac. Hailing from the village of Pawtuxet, Cranston, he entered military service as a private and left it four years later as a colonel. Written in plain, direct style, his diary is full of insights into Army life, his spirit of service, his battle experiences, and his religious faith and drive to see the war to its conclusion.18Robert Hunt Rhodes, ed. All for the Union: The Civil War Diary and Letters of Elisha Hunt Rhodes, (NY: Vintage Books, 1985)

Burns’ popular documentary also brought belated fame to Sullivan Ballou, a Smithfield native who had attended Brown University. When war broke out, he immediately enlisted as a Major in the Second Rhode Island Infantry. In July 1861, anticipating that he would soon see combat, he wrote a moving letter, discovered only decades later, to his wife, Sarah, describing his conflicting feelings of duty to his family and his country. A devoted husband, loving father, and idealistic leader, Ballou was killed two weeks later at the Battle of Bull Run. He was 32 years old.

Ballou and Rhodes were little known at the time. Rhode Island’s most famous military figure during the war itself was Ambrose Burnside, whose reputation rose rapidly in the conflict’s first years. In July 1861, at the First Battle of Bull Run in Virginia, Rhode Island, units led by Colonel Burnside led the assault at a place called Matthew’s Hill. One soldier, Colonel John Stanton Slocum, fell in battle as he cheered on his men, exclaiming, “Now show them what Rhode Island can do!” These words became a rallying cry for Rhode Island troops over the next four years.19Robert Grandchamp, Rhode Island and the Civil War: Voices from the Ocean State (Charleston: The History Press, 2012), 25

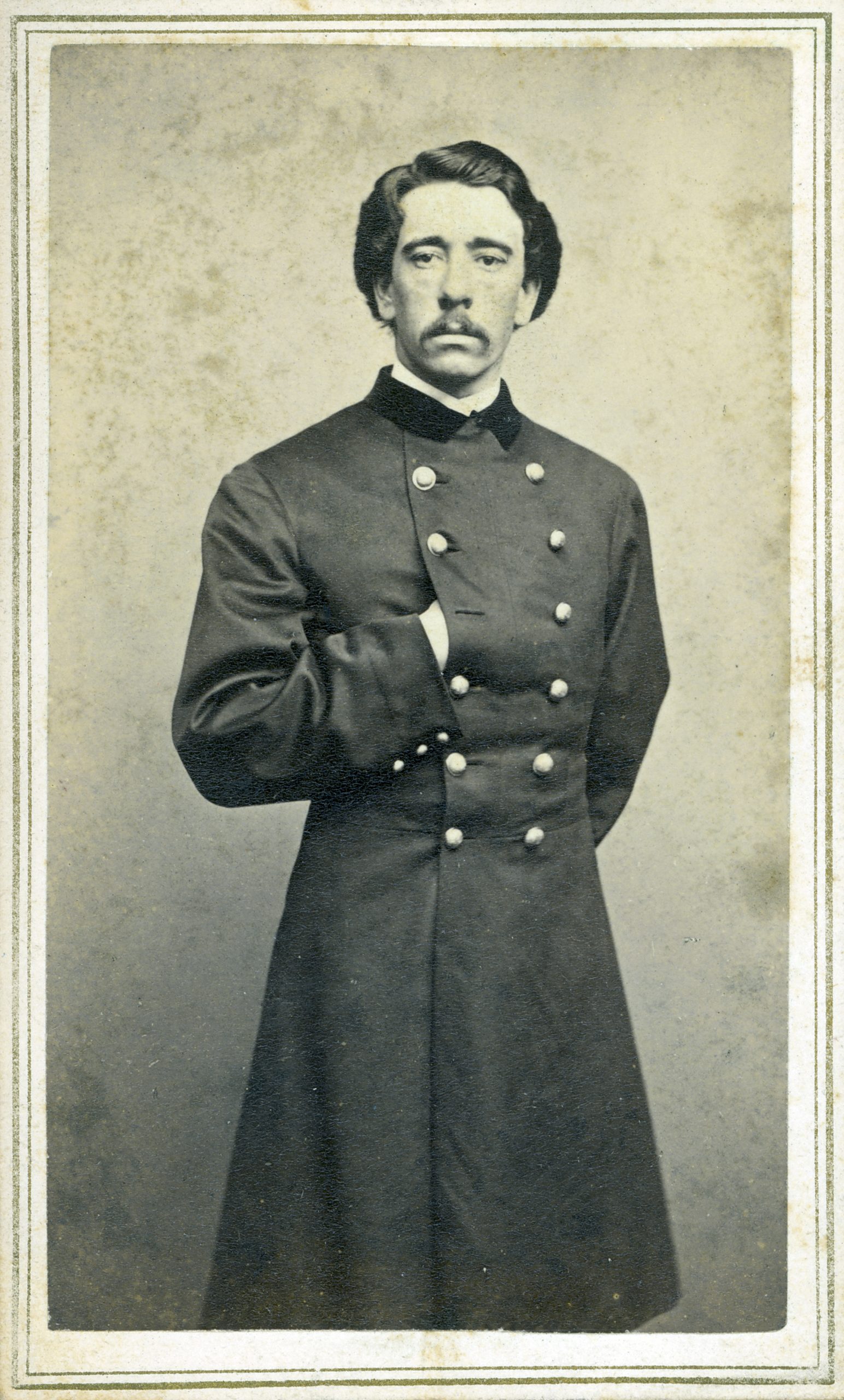

Photograph of Kady Brownell

Learn more about the legendary Kady Brownell here

Many thought that the battle at Bull Run, the war’s very first major engagement, would see the Rebels flee at the sight of the mighty Union Army, but these expectations were quickly dashed.

Robert Brownell of Providence would see action at Bull Run, and so did his wife, Kady. When Robert enlisted in the 1st RI Regiment, and the unit left for the nation’s capital, Kady followed. Both took part in the First Battle of Bull Run, with Kady serving as temporary standard bearer. She also accompanied her husband later in the war with the 5th RI Heavy Artillery and saw action in North Carolina. Kady then served as a nurse and standard bearer.20Frank L. Grzyb, Hidden History of Rhode Island and the Civil War, (Charleston: History Press, 2013), 98-102 The Brownells’ remarkable story underscores the patriotism and devotion with which many Rhode Islanders served.

After the Northern Army’s shocking defeat at Bull Run, Governor Sprague again issued calls for troops. Union leaders realized that the war would not be brief. General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia would prove to be a skilled and determined foe. By the end of 1861, the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Infantry Regiments were moving to the Carolinas for action. Eight batteries were trained for the First RI Light Artillery Regiment. The First RI Cavalry was also organized.21Grandchamp, 25-26

In the winter of 1862, Ambrose Burnside, by then a Brigadier General, launched an amphibious assault on the coast of North Carolina. The 4th RI led the decisive charge at the Battle of New Berne.22Grandchamp, 27-29 Thanks to his valiant service at Bull Run and his successful expedition to North Carolina, promotions came quickly.23Dunkelman, Mark H. “Rhode Island Civil War Generals.” Accessed May 21, 2019 [link] Burnside was already the most renowned Rhode Island Civil War officer.

The second year of fighting saw much heavy combat and involvement of RI troops. In the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, the 1st RI Cavalry saw heavy action. In the Peninsular Campaign, the 2nd RI and five batteries of artillery engaged the enemy, fighting at Fair Oaks and the Seven Days Battles as part of the Army of the Potomac.24Dunkelman At Fair Oaks, in May 1862, Brigadier General Silas Casey of East Greenwich, RI, led the 2nd Division of the 4th Army Corps. Casey’s division was posted in an advanced position near Richmond, the Confederate capital. That afternoon the Confederates launched a major counteroffensive in which Casey’s division lost more than 1,400 men. His career suffered in the wake of the defeat, and he saw no more active service.

Nevertheless, General Casey stayed in the army and found other ways to serve—as an instructor. In 1862, the Army chose to use his book on infantry tactics. On the outskirts of Washington, he trained thousands of new recruits from all over the North, receiving, organizing, instructing, and forming the new regiments into provisional brigades and divisions.25Dunkelman

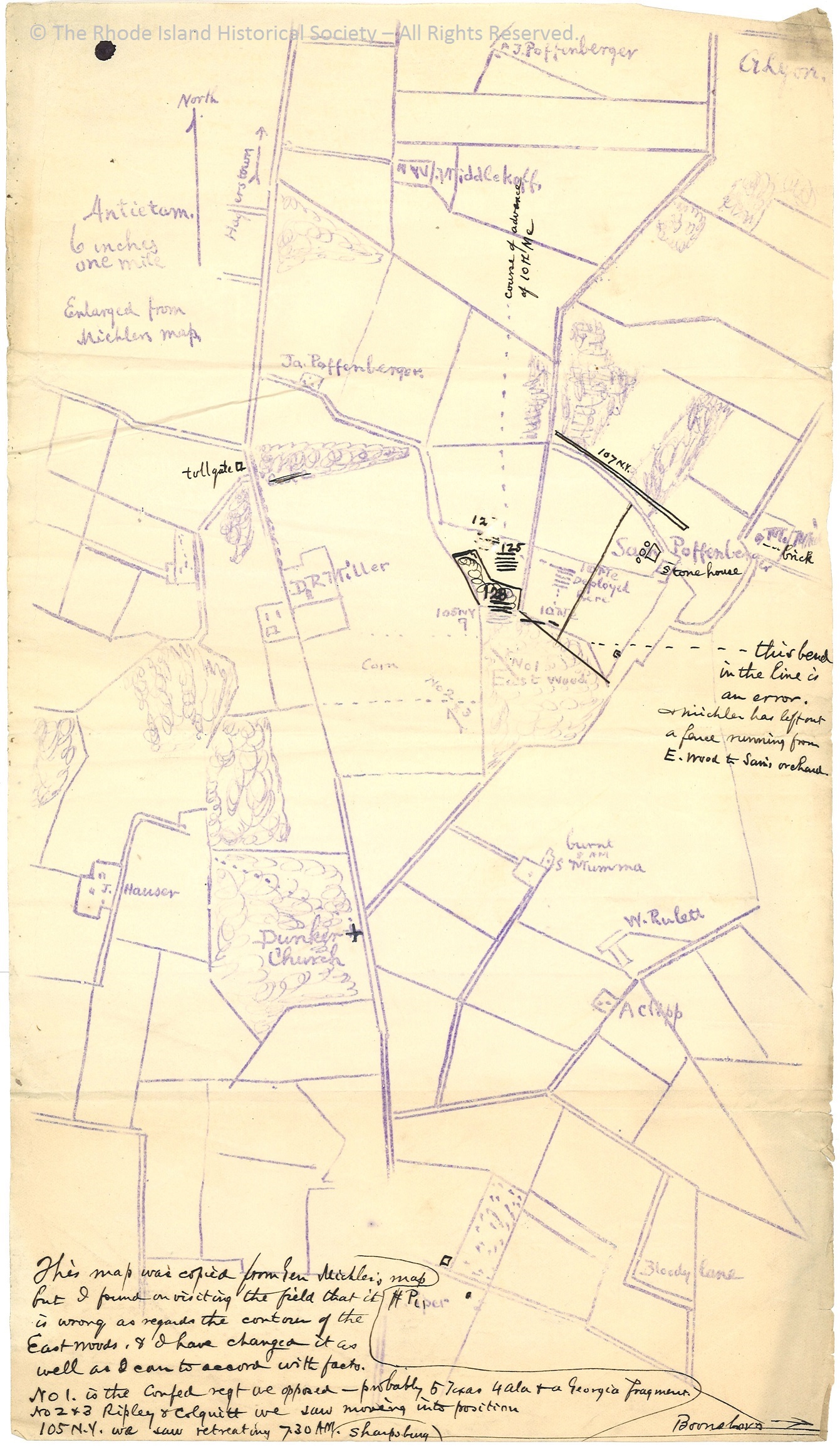

In September 1862, Rhode Island units were heavily involved in the momentous Battle of Antietam. The “bloodiest day in American history” ended with over 23,000 men killed or wounded. The 4th RI plus Batteries A, D, and G lost heavily in fighting at Dunker Church, Bloody Lane, and Otto’s Farm.26Grandchamp, 29 Although the battle was a stalemate, it was close enough to a victory that it prompted Lincoln to issue his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

Annotated Map of Gettysburg

Learn more about Brigadier General George Sears Greene here

The worst day of the war for Rhode Island troops came in Virginia in December 1862, at the Battle of Fredericksburg, with General Burnside commanding the Army of the Potomac, the principal army for the Union in the Eastern region of the war. His army confronted General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia. In the largest-ever concentration of RI units, the state was represented by the 2nd, 4th, 7th, and 12th Regiments, the 1st RI Cavalry, and Batteries A, B, C, D, E, and G of the 1st RI Light Artillery. Thousands of RI troops attacked, and many died below a hill known as Marye’s Heights.27Grandchamp., 29-31 Drummer William P. Hopkins of West Greenwich lamented, “Barrels of blood had been poured on the ground.” Union casualties numbered almost 13,000; seventy-five Rhode Islanders were killed, and over 300 were wounded. Burnside, who had ordered an ill-advised attack, accepted blame for the defeat and was transferred to the West.28Grandchamp, 29-31 His national reputation never recovered. But Rhode Islanders were apparently forgiving: after the war, he was elected governor and senator. Today, however, he is best remembered for giving his name to “sideburns,” and not for his military prowess.

In a bold strategic move to end the war quickly on the South’s terms, General Lee moved his army into the North, bringing the Army of Northern Virginia into south-central Pennsylvania, where the largest and probably most significant battle of the war took place. In July 1863, at the Battle of Gettysburg, the Union Army under General George Meade turned back the Confederates. Rhode Island units again performed capably. Three artillery batteries played central roles, and the 2nd RI arrived just in time to help on the battle’s third and final day after a 40-mile forced march.29Grandchamp, 31

One of Gettysburg’s oldest participants was a Rhode Islander, Brigadier General George Greene. Born in Apponaug, he graduated from West Point in 1823 and was 61 years old when the war began. Commanding the 60th New York Volunteer Infantry, he led his unit’s heroic defense of Culp’s Hill. Successful action at Culp’s Hill and the more well-known Little Round Top helped to determine the outcome of not only the battle of Gettysburg but also the entire war.

Just as Gettysburg was being fought, General Ulysses Grant forced Vicksburg, a Confederate fortress on the Mississippi River, to surrender, putting the Union on the road to victory in the West. Rhode Islanders, including George Greene, also fought in the western campaigns. Later that year, in a night battle at Wauhatchie, Tennessee, a bullet ripped through General Greene’s jaw and put him out of the war, but only temporarily. After recuperating from a difficult surgical procedure, Greene rejoined the army in time to participate in General William T. Sherman’s final campaign in North Carolina.30Dunkelman

The War Comes to an End

After Gettysburg, Rhode Island units fought bravely throughout the remaining two years of the war, often under General Grant at The Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Po River, North Anna, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg.31Grandchamp., 31-33 These battles were part of Grant’s campaign to weaken Lee’s army and capture the Confederate capital at Richmond. Some of these battles, including Cold Harbor and Spotsylvania, were among the most devastating of the war. On April 2, 1865, soldiers from the 2nd RI and Battery G were part of the force that seized Petersburg, which proved to be the final, decisive blow against the once mighty Army of Northern Virginia. Shortly afterward, Lee surrendered at Appomattox.32Grandchamp, 33

During the Civil War, Rhode Islanders fought with valor and showed the country “what Rhode Island can do.” In addition to fighting the battles, Rhode Island men and women supported the Union cause on the home front. Had he lived to see the war’s end, Colonel John Slocum would have been proud.

Terms:

Mobilize: to activate and assemble military forces

Logistical support: supplies of arms, ammunition, uniforms, and the like provided by civilian and military effort

Arms: weapons, most notably the Springfield Rifle, manufactured in western Massachusetts

Quota: the minimum number of men to enlist

Battery: an artillery unit or sub-unit that belongs to a company

Artillery: units consisting of gunners and cannons

Steamer: a steamship

Mustered: to assemble or gather. To enlist into military service

Infantry: foot soldiers

Calvary: unit on horseback

Blockade runner: a ship used to enter or depart a port blockaded by the enemy

Scythe Works: a factory that makes sharp agricultural tools used for cutting crops

Martyrdom: death for a cause

Standard bearer: one who carries the unit flag

Brigadier General: a senior military rank

Amphibious: military forces coming to land from the sea

Tactics: battlefield maneuvers and movements

- 1William G. McCloughlin, Rhode Island, A History. NY: W.W. Norton, 1978

- 2Patrick T. Conley, An Album of Rhode Island History, 1636-1986. RI Publications Society, 1986

- 3See map of American Civil War battle sites [link]

- 4Rhode Island Civil War Centennial Commission. Rhode Island Civil War Chronicles: A Presentation of Articles and Photos Recalling Rhode Island’s Participation in the Civil War, 1861-1865, 1960, 5-6; Robert Grandchamp, Rhode Island and the Civil War: Voices from the Ocean State, (Charleston: The History Press, 2012), 19-25

- 5Mathias P. Harpin, The High Road to Zion (Harpin’s American Heritage Foundation, 1976), 148

- 6Rhode Island Civil War Chronicles, 11

- 7Frank J. Williams, foreword to Rhode Island and the Civil War: Voices from the Ocean State., Robert Grandchamp, (Charleston: The History Press, 2012), 12, Appendix I

- 8Williams, 12

- 9Williams, 109-113

- 10Williams, 109-113

- 11“Rear Admiral William Rogers Taylor, USN, (1811-1889)“ Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed 14 April 2020 [link]

- 12Frank L. Grzyb, Rhode Island’s Civil War Hospital: Life and Death at Portsmouth Grove, 1862-1865 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2012)

- 13Rhode Island Civil War Centennial Commission. Rhode Island Civil War Chronicles; Frank L. Grzyb, Hidden History of Rhode Island and the Civil War, (Charleston: History Press, 2013), 34-37

- 14Maury Klein, “Rhode Island’s Civil War Economy,” in The Rhode Island Home Front in the Civil War Era, eds. Frank J. Williams and Patrick T. Conley (Nashua, NH: Taos Press, 2013), 55-77

- 15Katharine Prescott Wormeley, The Other Side of War with the Army of the Potomac: Letters from the Headquarters of the United States Sanitary Commission during the Peninsular Warm 1862 (Boston: Tickner and Co., 1889), 5

- 16This song refers to John Brown, the abolitionist of Harper’s Ferry, VA fame, not to John Brown of Rhode Island

- 17“Master of Vineyard Calls Woman Patriot,” Record-Herald, October 18, 1910; “Julia Ward Howe,” accessed May 21, 2019 [link]

- 18Robert Hunt Rhodes, ed. All for the Union: The Civil War Diary and Letters of Elisha Hunt Rhodes, (NY: Vintage Books, 1985)

- 19Robert Grandchamp, Rhode Island and the Civil War: Voices from the Ocean State (Charleston: The History Press, 2012), 25

- 20Frank L. Grzyb, Hidden History of Rhode Island and the Civil War, (Charleston: History Press, 2013), 98-102

- 21Grandchamp, 25-26

- 22Grandchamp, 27-29

- 23Dunkelman, Mark H. “Rhode Island Civil War Generals.” Accessed May 21, 2019 [link]

- 24Dunkelman

- 25Dunkelman

- 26Grandchamp, 29

- 27Grandchamp., 29-31

- 28Grandchamp, 29-31

- 29Grandchamp, 31

- 30Dunkelman

- 31Grandchamp., 31-33

- 32Grandchamp, 33