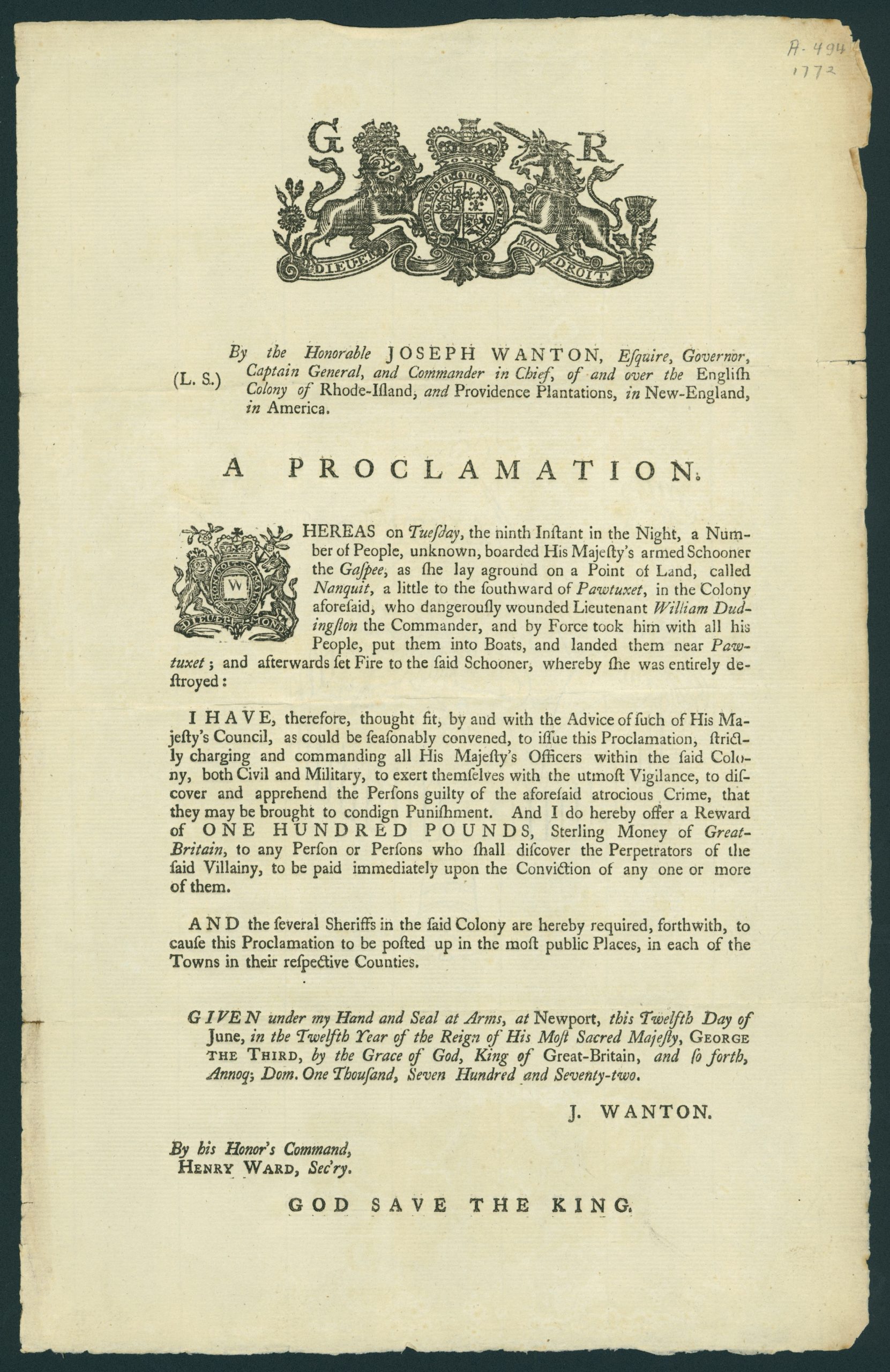

A Proclamation by Governor Wanton

Published on June 12, 1772, this proclamation by Governor Wanton established the first reward for information regarding the destruction of the Gaspee. Along with newspaper articles and gossip, this document was likely one of the first ways that Rhode Islanders found out about the incident. For us today, it might be difficult to read at first. For example, all the “s” letters throughout the piece look like “f,” because of an old grammar and printing tradition. This style of “s” began to be phased out about thirty years later. Read the document and examine Wanton’s explanation of the incident. What words does he use to describe the destruction of the Gaspee?

Governor Joseph Wanton and the Controversial Commission

Sean Gray, Rhode Island Historical Society Intern, Student at Providence College

The destruction of the Gaspee put Rhode Island Governor Joseph Wanton in a difficult place. The British government formed a commission to investigate the ship’s destruction, and Wanton was put in charge of it. As the governor of a royal colony, he was supposed to remain loyal to the British government across the Atlantic Ocean. At the same time, however, he had the responsibility of acting in the best interest of his colony. Wanton was forced to choose a side: would he investigate the destruction of the ship properly, risking the lives of his colonists, or use his power to slow it down and thereby protect Rhode Islanders?

In the 1700s, Rhode Island’s economy depended almost entirely on trade, specifically the trade of molasses and rum. Because Rhode Island was, at the time, a colony of the British Empire, the British government legally controlled who Rhode Island could trade with and what they could trade.1Steven Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee: An Attack on Crown Rule Before the American Revolution. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing. 2016. p. 3-6 While Britain could make strict laws about Rhode Island’s trade, it often chose not to enforce these laws. Any trip between Rhode Island and Great Britain would take about two months, making clear communication and strict enforcement difficult and impractical. These practical difficulties led Britain to choose not to enforce their trade laws harshly, and this practice came to be known as “salutary neglect,” or ignoring the law to the benefit of most. As a result, Rhode Islanders in the 1760s likely came to expect a relaxed attitude from British ships in the area regarding trading laws.2Park 4 But after an expensive war with France to defend the colonies, Great Britain needed to pay off its debts, and it began harshly enforcing laws. For Rhode Islanders, this meant a stricter enforcement of molasses and rum taxes. Rhode Island traders could thus no longer avoid taxes like they previously had by smuggling. They spent much of the decade in protest: against the Stamp Act, the Townshend Act, and other laws that tried to change Rhode Island’s economic relationship to Great Britain.3Park 4

The arrival of Royal Lieutenant William Dudingston and the Gaspee early in 1772 was the embodiment of the strict enforcement of and obedience to the law for Rhode Islanders. Dudingston was sent to enforce the laws and collect duties at any cost. Notably, he stopped Nathaniel Greene and his brother’s sloop Fortune on February 17, 1772, and seized their cargo of rum, sugar, and other spirits. The Greenes had sought to avoid paying taxes on these products when selling them, but now, the products were the property of the British Empire.4Park 10

This incident with the Greenes was not the only one to inspire resentment towards the Gaspee. For months prior to the ship’s destruction in June of 1772, Governor Wanton had heard complaints from prominent merchants across the colony who claimed the Gaspee’s crew and its commander, Dudingston, had been tyrannizing the coastline of Rhode Island. Darius Sessions, Rhode Island’s lieutenant governor, claimed that Dudingston was constantly “chasing, firing at, searching” ships and then “often treating the people on Board in the most abusive language.”5Peter Messer, “’A Most Insulting Violation:’ The Burning of the HMS Gaspee and the Delaying of the American Revolution.” The New England Quarterly. v. 88, no. 4. December 2015. p. 587

John Brown, one of the colony’s wealthiest and most powerful men, was particularly upset at the impact Dudingston and the Gaspee had on his maritime business. Many wealthy Rhode Islanders like Greene and Brown depended on trade, both legal and illegal, for their profits, and they felt that Dudingston’s methods of enforcement seriously hurt that trade. Merchants were no longer able to ignore these taxes, and they became fed up.6Charles Rappleye, Sons of Providence: The Brown Brothers, the Slave Trade, and the American Revolution. New York: Simon and Schuster. 2006. p. 105

Eager to maintain peace between Dudingston and the colonists, Wanton tried to meet with the Gaspee’s commander in person several times, but Dudingston often refused. As a Royal Navy officer, Dudingston believed he had more power than Wanton, and he wanted to enforce the law on his terms, not Wanton’s. Yet Dudingston failed to realize that Wanton, unlike many governors, was not appointed by the Crown; the Rhode Island state legislature had elected him, and he was, therefore, beholden to the citizens of Rhode Island. Dudingston’s refusal to cooperate with the government of Rhode Island led to increased tensions between local Rhode Islanders and the British Navy, and so the subsequent destruction of the Gaspee in June of 1772 was likely not a surprise for Wanton.

Once the ship was destroyed, Wanton knew he had to carefully weigh his decisions in order to keep violence from escalating further. Explaining Wanton’s strategy, historian Peter Messer writes that Wanton responded with a “combination of outrage calculated to convince the imperial government of his desire to punish the perpetrators of the attack and studied foot-dragging to ensure that punishment never happened.”7Peter Messer, “’A Most Insulting Violation,’” 584 Essentially, Wanton wanted to convince the British government that he would apprehend the perpetrators, but he secretly tried to make sure that the perpetrators would never be discovered. Above all else, he wanted to maintain a peaceful status-quo in the colony.

On June 12, 1772, Wanton issued a proclamation from the Rhode Island government.8 Read more in our blog post by Jessica Chandler [link] He wrote that an “unknown” number of men boarded the Gaspee, “dangerously wounded” its commander William Dudingston, and “afterwards set fire to the schooner, whereby she was entirely destroyed.” To conclude his proclamation, Wanton offered a reward of one hundred pounds, a good amount of money, “to any person or persons who shall discover the perpetrators of said villainy.”9Joseph Wanton, “A Proclamation,” June 12, 1773 In this document, it seemed like Wanton wanted to know which Rhode Islanders were involved in the raid, the “perpetrators,” and he was willing to pay a good price for this information. But beyond posting this proclamation, he took no action to find the attackers. Moreover, no Rhode Islanders came forward with any information for almost a month. The investigation into the attack had seemed to reach a dead end.

That changed in early July, when a young man named Aaron Briggs fled his home on Prudence Island in Narragansett Bay to the British ship Beaver stationed nearby.10Read more in our essay about Aaron Briggs [link] Though the historical record is not definitive whether Briggs was an indentured servant or a slave, he was clearly dissatisfied with his life on Prudence Island. Upon arriving at the Beaver, he confessed that he participated in the Gaspee raid. Admiral John Montagu, Lieutenant Dudingston’s superior stationed in Boston, was thrilled to hear Briggs’ story. Up to this point, the only witnesses who had come forward were Gaspee crew members, and Briggs’ story matched up well with theirs. More importantly, as a local, Briggs identified specific men involved with the raid—something the crew of the Gaspee could not do. After a month without progress, Montagu hoped that Briggs’ testimony could jumpstart the investigation. In a letter on July 8th with Briggs’ statement enclosed, Montagu ordered Governor Wanton to arrest John Brown and Simeon Porter for their leadership in the raid.11Admiral Montagu to Joseph Wanton, July 8, 1772, in Colonial Records of Rhode Island, ed. John Bartlett. 1862. p. 93 In order to maintain peace within the colony, however, Wanton knew that he could not arrest the powerful Brown and Potter. He quickly set out to investigate Briggs’ story.

Only days after receiving Montagu’s letter, Wanton deposed four men whose testimonies directly contradicted Briggs’ story. After hearing these conflicting testimonies, Governor Wanton wanted to question Briggs himself, but the crew of the Beaver refused to hand him over. Fearing for Briggs’ safety after he had implicated some of Rhode Island’s most powerful men in the Gaspee affair, the British held him aboard the Beaver for months. He was their best witness, and they did not want to take any unnecessary risks with his life.

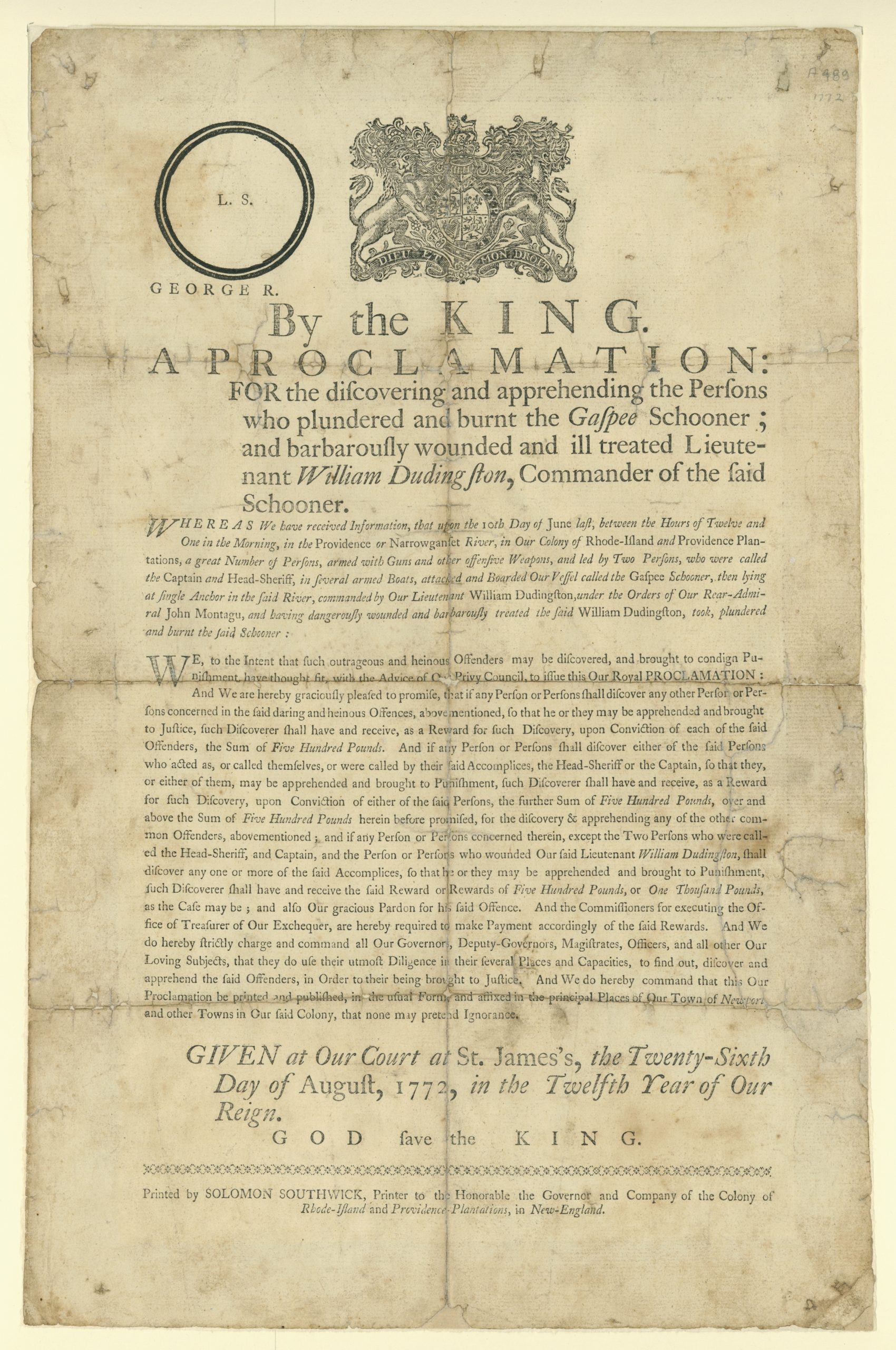

By August, the investigation seemed stalled again. Perhaps frustrated by the lack of progress, at the end of the month King George III himself issued two more proclamations. The first raised the reward from 100 to 500 pounds. The second was even more important. King George called for the creation of a royal commission to investigate the ship’s destruction. This “Commission of Inquiry” was composed of five men: Joseph Wanton, governor of Rhode Island, the chief justices of the colonies of New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts Bay, and lastly, a judge at the Boston vice-admiralty court. King George ordered these men to lead a formal investigation into the destruction of the Gaspee, and controversially, he demanded that any suspects should be arrested and sent to Britain for trial. Normally, any person arrested and charged with a crime would be judged by a jury of his peers, a tradition in British law that dates back to the thirteenth century. King George, however, was so angry about the destruction of the Gaspee that he wanted to sidestep this process in order to punish the perpetrators more directly. Doubting that Rhode Islanders would punish the perpetrators properly, King George wanted to do it himself.

King George’s proclamation inspired outrage across the colonies. Two pieces from the Providence Gazette offer perspective into why the commission caused so much anger among Rhode Islanders. On December 19, 1772, one article said: “The idea of seizing a number of persons, under the points of bayonets, and transporting them three thousand miles for trial…is shocking to humanity, repugnant to every dictate of reason, liberty, and justice.” The author of this article saw the dangerous potential of the commission. If anyone arrested was taken to Britain rather than standing trial in Rhode Island, Rhode Islanders might see that as kidnapping. A second article, written by the Rhode Island Attorney General under the pseudonym Americanus and published on December 26, 1772, offered more insight into the Rhode Islanders’ fears. “The persons who are the commissioners of this new-fangled court are vested with the most exorbitant and unconstitutional power…To be tried by one’s peers is the greatest privilege a subject can wish for; and so excellent is our [British] constitution, that no subject shall be tried, but by his peers.” This new commission, Americanus thought, composed of royal officials from throughout the British empire, was in no way made up of their peers.

These newspaper articles, however, did not stop the commission from meeting. It first met in January of 1773, and Wanton served as the de facto leader of the commission. He set the pace of the commission’s investigation early. Charles Rappleye writes that Wanton “made clear…that they would not make arrests on their own, but only in concert with, and through the offices of, local officials and colonial courts.”12Charles Rappleye, Sons of Providence, 120 Because Wanton was a local politician, he understood how important public support was in this investigation. He faced an important choice in satisfying either his local community members or the officials who governed the British empire. If the commission angered the public, peace in the colony could be threatened; mobs and riots could form, and Wanton, like other colonial governors such as Thomas Hutchinson, might even be burned in effigy. As the commission’s first day of interviews approached, Wanton faced a difficult decision in how he would run it.

Meeting in Newport in January 1773, the commission interviewed ten witnesses. Most central to this meeting was the testimony of Aaron Briggs and Wanton’s work to discredit the testimony almost immediately afterward. As Briggs testified, his story seemed to have changed from the first time he testified. When he spoke about his time aboard the Beaver, it seemed as if the captain of the ship forced Briggs to make up his story. Briggs described being chained up and threatened with beatings, only to be saved at the last second once a Beaver crewman claimed to recognize him from the raid. Wanton capitalized on the context of Briggs’ testimony to make it seem significantly less credible. After two weeks of interviews, the commission was no closer to discovering the truth, thanks in large part to Wanton’s efforts. In a progress report likely written by Wanton, the commission complained about how British officials barely helped the investigation. The commission, then, was no further in finding the truth. Citing “severe weather” as their reason for ending the January session, the commission agreed to reconvene in the summer to continue their work.

The commission met for a second time in the summer of 1773. They continued to interview more witnesses in hopes of finding the perpetrators. As Steven Park notes, “Witnesses were summoned and arrived according to a schedule whereby anyone who might recognize another was not called to the Colony House [where the commission met] on the same day.”13Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee, 71 Again, Wanton made sure that nothing would come of the commission’s interviews. Even though Briggs implicated John Brown and other prominent Rhode Islanders in the event, they were never called to testify themselves. After another few unsuccessful weeks, the committee decided to close the inquiry and write a final report. The commission believed that a British naval captain had forced Briggs to make the story up in order to help the investigations. In a private letter, one of the investigators even believed that a British sailor had prepared Briggs to testify, coaching him about proper answers to questions from the commissioners.14Steven Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee, 128 Moreover, the final report explained that the Gaspee’s captain’s behavior incited the colonists to violence. If he had not acted with extreme disrespect and disdain towards the colonists for no specific reason, they probably would not have struck back with such violence. The final report, then, was harsher towards British officials than the perpetrators of the incident.

Even though the commission failed to charge the perpetrators of the destruction of the Gaspee during its investigation, it was still significant in two important ways leading up to the revolution. First, the commission’s broad legal powers, the ones that inspired citizens to write articles in Rhode Island newspapers, shocked colonists throughout the colonies, most notably in Virginia. Consequently, the House of Burgesses, Virginia’s state legislature, created in March of 1773 the first committees of correspondence to remain up-to-date about the commission’s investigation in Rhode Island. With the purpose of sharing information across and between colonies in a time where information traveled incredibly slowly, these committees of correspondence were one of the first times the colonies “teamed up” to work as one unit organizing against Great Britain. As important conflicts between the British and the colonists happened throughout the colonies, like the Boston Tea Party and the closing of Boston Harbor in the coming years, the committees wrote to each other to remain informed and plan protests.

Second, the Gaspee commission’s power was a central topic in Minister John Allen’s sermon An Oration, Upon the Beauties of Liberty, or the Essential Rights of Americans, published in December of 1772. He argued that the powers the British government gave the Gaspee commission were unjust, and if the American colonies were really an equal part of the British empire, then they should have been treated as equals under investigation. John Allen ultimately concluded that “the legal and jurisdictional sphere of the Americans was different from the sphere of the English, and the two could not be reconciled.”15Park 88 Essentially, the American colonists were not legally treated the same way as British subjects in England, and this difference could never be fixed. This conclusion was shocking and powerful to many. Allen published the twenty-seven-page pamphlet, and it became one of the most widely distributed, most influential, and most important pamphlets written before the American Revolution.

Four years before the American Revolution began, the Gaspee commission’s investigation was a confusing, controversial, and important episode in Rhode Island’s history. Though the commission itself did not apprehend any perpetrators, its mere existence sparked a call to action for colonists across North America. Perhaps most interesting was the involvement of Governor Wanton. His behavior raises important questions about duty, power, and public service that we should continue to ask ourselves and our officials today, such as what are the purposes of government? To what lengths should it go to maintain peace or enforce justice?

Terms:

Commission: a group of people tasked with investigating an important even

Royal colony: a colony owned by the king, who chooses a governor to manage it

Tyrannizing: ruling over someone unfairly

Tensions: when two forces put pressure on an object; conflict

Perpetrator: someone who does something harmful or illegal

Foot-dragging: delaying/taking your time to make a decision

Status-quo: how things have been for a while; the normal way things go

Proclamation: a public announcement regarding an important matter

Indentured Servant: an unpaid laborer who receives freedom in exchange for a set number of years of service

Depose: to question a witness

Implicate: to say that someone is involved in a crime

Royal Commission: a group formed to formally inquire the public about an issue

Vice-admiralty: related to the ocean, ships, and the navy

Repugnant: unacceptable

De facto: something not written in law, but accepted as true in reality

Committees of correspondence: a formal institution and means for the American colonies to communicate with each other

Sermon: a talk, lecture, or speech normally given during a church service on an important matter, like religion or politics

Questions:

Why did the arrival of the Gaspee create problems for Governor Wanton? What two pressures did he face?

Why was the creation of the commission of inquiry so controversial?

What were the final conclusions of the Gaspee commission? How did they reach these conclusions?

Why was the Gaspee commission important across the colonies?

- 1Steven Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee: An Attack on Crown Rule Before the American Revolution. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing. 2016. p. 3-6

- 2Park 4

- 3Park 4

- 4Park 10

- 5Peter Messer, “’A Most Insulting Violation:’ The Burning of the HMS Gaspee and the Delaying of the American Revolution.” The New England Quarterly. v. 88, no. 4. December 2015. p. 587

- 6Charles Rappleye, Sons of Providence: The Brown Brothers, the Slave Trade, and the American Revolution. New York: Simon and Schuster. 2006. p. 105

- 7Peter Messer, “’A Most Insulting Violation,’” 584

- 8Read more in our blog post by Jessica Chandler [link]

- 9Joseph Wanton, “A Proclamation,” June 12, 1773

- 10Read more in our essay about Aaron Briggs [link]

- 11Admiral Montagu to Joseph Wanton, July 8, 1772, in Colonial Records of Rhode Island, ed. John Bartlett. 1862. p. 93

- 12Charles Rappleye, Sons of Providence, 120

- 13Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee, 71

- 14Steven Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee, 128

- 15Park 88