Narragansett History

Essay by Lorén Spears, MsEd.,Narragansett, Executive Director of Tomaquag Museum

The Narragansett people sought balance with the land. They believed that everything they needed was a gift from the Creator. Each season provided the materials they needed for their lives. Thirteen Moons or months brought new lifeways. Lifeways is a word used to explain how people meet the needs of daily life. Examples of lifeways include hunting, fishing, growing, and gathering the materials for their food, clothing, homes, travel, tools, household items, games, medicines, and ceremonial items. Everything the Narragansett needed to sustain their lifeways came from this land. The “Nahahiganseck,“ known as the “people of the small point” were, and still are, an eastern, woodland, coastal people. The Narragansett territory encompassed most of what is considered the state of Rhode Island today. In each moon there are different harvests that are marked with a thanksgiving ceremony. The one celebrated today by Americans in November represents the Autumn Harvest Thanksgiving. The Narragansett traditionally celebrate thirteen Thanksgivings, one for each new moon, giving thanks for the gifts from the Creator, the land, and its waters that sustain(ed) our(their) lifeways.

The Narragansett lived in inland villages during the winter months and in coastal villages during summer months. In the winter, the arbor of trees protected the villages from the harsh weather. These villages were located near sources of fresh water, especially springs. They were also close to abundant hunting grounds, freshwater ponds that, when frozen, could be used for ice fishing, and forested areas that not only provided wood for their “Nusqweetoo” or longhouse but also for cooking fires and granted access to other harvestable resources. In the spring, the Narragansett moved to their summer villages located along the bay, near salt ponds and ocean waters that provided fresh food. The community also used seaweed and fish to fertilize the gardens as part of their agricultural work.

Each Narragansett village was comprised of about 500 people, including men, women, children, and elders who worked together to harvest the resources needed to sustain their lifeways. The Narragansett men made, set, and used fishing weirs, a type of fencing in the water, to guide the running fish, such as bluefish, striped bass, and cod. The goal of the weir is to slow down the fish enough to capture only enough for what was needed. The fish would be caught by spearing or netting them. Later they would be dried and smoked, usually by women, to preserve for the winter. The gardens were prepared by the men and tended by the women and older children to grow bean, squash, melons, and other crops. Corn, bean, and squash were grown together in the same garden and are known as the Three Sisters because they have a symbiotic relationship. The squash keeps in moisture by acting like mulch. The bean provides nitrogen, which is a kind of nutrient. The corn stalk provides a place for the bean to grow upon. Throughout each of the seasons, the people hunted, fished, grew, and gathered the resources for the items they needed, such as baskets, tools, cooking pots, blankets, clothing, dyes, mats, canoes, homes, and other items to fulfill their needs. The Narragansett worked together in a communal manner to ensure the well-being of the community.

The Narragansett were a large tribal nation, and were the largest nation in the area. They had many allies and created alliances with nearby tribal nations, including the Wampanoag, Niantic, Nipmuk, and Shinnecock. These tribes had a kinship relationship and respected each other’s leadership. The Narragansett had clear territorial boundaries. The warriors protected not only their villages but also supported the protection of the neighboring nations from their enemies during times of conflict. Leaders used diplomacy to solve conflicts when possible. Within this kinship network, they also visited, traded, and married, which deepened the relationships between nations.

European Conquest Causes Change

Giovanni da Verrazzano is considered the first European explorer to visit Narragansett Bay. He reported to King Francis in 1523 regarding the appearance and temperament of the Narragansett people he encountered. “These people are the most beautiful and have the most civil customs that we have found on this voyage.”1Letter to King Francis I of France from Giovanni da Verrazzano reporting his voyage to the New World [link] However, as more explorers and settlers came to trade, they brought disease that affected the Indigenous population of the region. In some cases, disease decimated whole villages of people.

The Landing of Roger Williams

Learn about the enslavement, displacement, and re-connection of the Narragansett here

In 1635, Roger Williams was expelled from the newly formed Massachusetts Bay Colony and traveled south in 1636. In their search for a new home, Williams and his followers were helped along in their journey by the Wampanoag people, and found a new home among the Narragansett people. The leaders Miantanomi and Canonicus allowed Roger Williams to create a settlement in what is now known as Providence.2To learn more about these Narragansett sachems (leaders), visit the Rhode Tour article highlighting their stories. [link] When the Narragansett leaders contracted the use of land with Williams, the Narragansett perceived this as an agreement where Roger Williams could utilize the land that was under Narragansett jurisdiction and that Williams and his followers were indebted to the Narragansett. However, the English settlers manipulated these agreements, did not uphold their obligations and asserted the signed documents as a purchase of land. At this time, the Narragansett had full sovereignty and understood they were allowing Williams to utilize the land within their territory and authority. However, Williams wanted to ensure a paper trail, to create his own authority on the land, garner power within the colonies and legitimize his legal standing to create a colony. This conflict of ideas is an example of oppositional perspectives on how land was to be used or owned and led to future conflicts between the two cultures. 3To learn more about Roger Williams and his dealings with tribal nations, listen to “Roger Williams and the Pequot War” from the Public’s Radio Mosaic podcast. [link]

The settlement by the English also caused changes in the land. Domesticated animals the English brought, which were not native to the area, such as cattle, pigs, and other livestock, destroyed the undergrowth of the forest, dug up clam beds, and destroyed corn fields and caches. The English put up large fencing around their farms and homes that promoted individual economies, meaning each household had its own property for its own uses, like farming or raising animals. This was a change for the Narragansett people. The Indigenous people had a communal economy and no understanding of individual land ownership in the European sense. This meant that they believed that land was to be used by all for the betterment of the whole community.

When more colonists came to the area, the expansion of the colony displaced the Narragansett and other Indigenous people in the area even further. Roger Williams recorded the Narragansett language, and many of their lifeways, and in 1643 went to England to have it published. In this book, titled The Key to the Language of America,4See a transcribed copy of The Key to the Language of America on Project Gutenberg [link] Williams wrote about the lifeways, language, government, spirituality, trade, and family life of the Narragansett people as he understood it from his perspective. Despite many positive reflections in the book, he was influenced by his Christian beliefs and goals for the English colony. He moved forward with his compatriots in a way that was not in the best interest of the Indigenous people, including sharing information with the Connecticut and Massachusetts colonies that impacted the Pequot War. The Narragansett remained a powerful nation, maintaining their sovereignty or authority and autonomy despite language within The Royal Charter5See a transcribed, annotated copy of the RI Royal Charter [link] that established the Colony of Rhode Island in 1663, which allowed the colonists to self govern, practice religious freedoms and it allowed the colonial power to “to invade and destroy the native .”

As a result of the increased conflict with the colonists, King Philip, a Wampanoag leader whose Indigenous name is Metacomet, went into war against the English colonists in 1675. Initially, the Narragansett remained neutral. However, on December 19, 1675, a military force raised by the United Colonies of New England raided the fort at Great Swamp in what is now known as South Kingstown, Rhode Island. The United Colonies feared that the Narragansett would soon join King Philip in the war against the colonists and massacred women, children, and elders who were there seeking protection, ensuing battles. In the traditional philosophy of combat, fighting men did not reside in the fortified locations. Typically, only civilians sought refuge in these areas, and they were, therefore, usually off-limits during conflicts. This massacre, along with other massacres, such as the massacre of the Pequot people in 1637,6Learn more about the Pequot War [link] was the beginning of the mass genocide of Indigenous peoples across the Americas.

Some of those who survived the massacre at Great Swamp and King Philip’s War were enslaved in the colony of Rhode Island and the Providence Plantations, and others were sold into slavery in the islands of the West Indies to work on plantations there. Roger Williams participated and profited from the enslavement of Narragansett refugees. This expanded the displacement of many of the people from their homelands. Those who remained in Nahahiganseck, joined together with their Niantic relatives and allies.

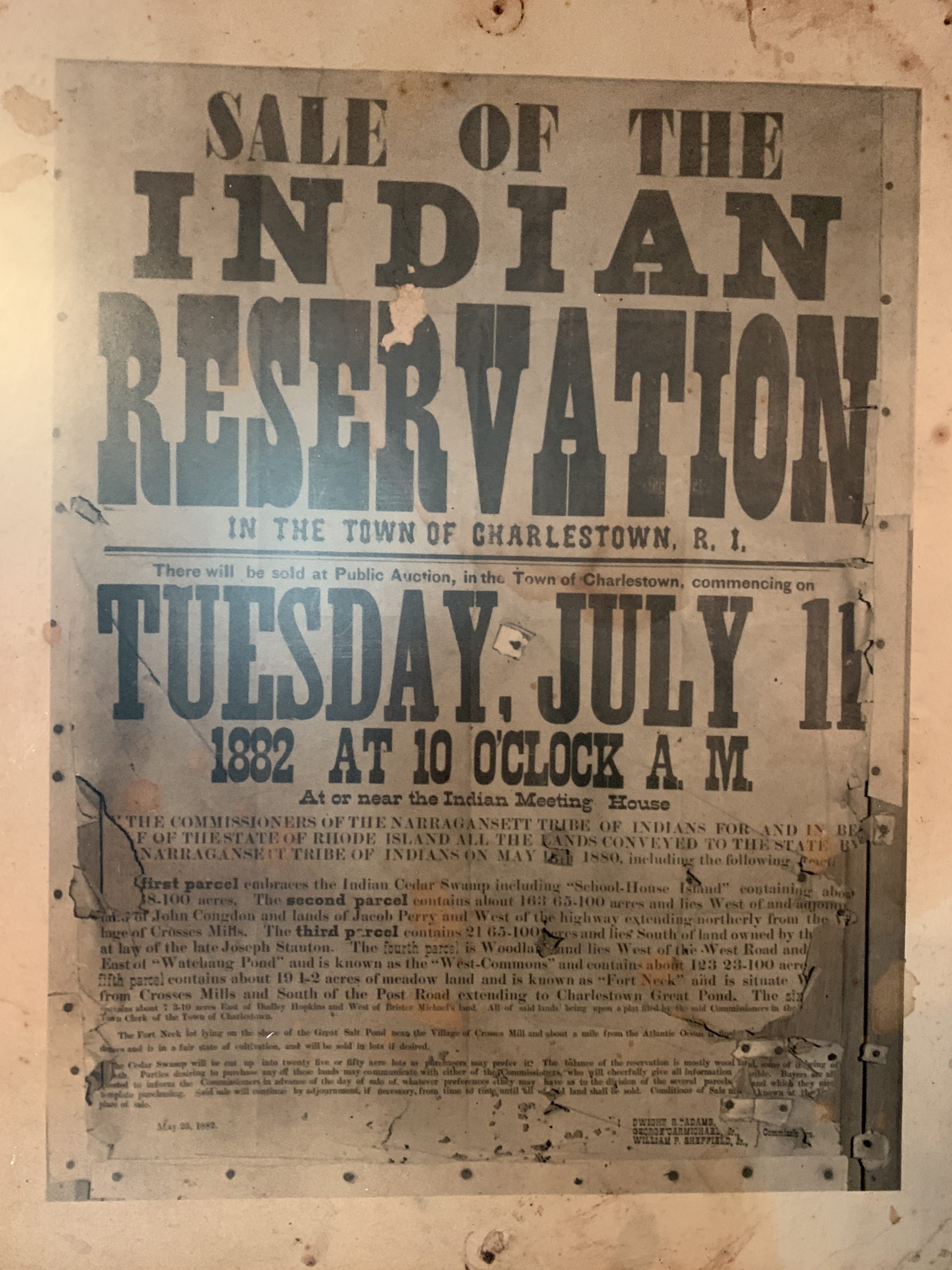

Broadside for the Sale of the Indian Reservation

Learn detribalization and Federal recognition of the Narragansett here

The Niantic and Narragansett merged as one people to increase their chances of survival. Along with dealing with enslavement and dispossession of their homeland, some Indigenous people were forced to assimilate into English culture through schooling, indentured servitude, continued enslavement, and forced religion.7Learn Sarah Muchamug’s story at Rhode Tour [link] Some chose to adapt to assimilative lifestyles and others tried to escape the oppression by fleeing north and then west, in what became known as the Brothertown Movement8Learn more about the Brothertown Movement [link]. The Niantic, Narragansett, Wampanoag, Pequot, Mohegan, and other Indigenous people moved north to Iroquois territory and then west, creating a settlement in Brothertown, Wisconsin. This movement began before the Revolutionary War, then was halted during the war, but then continued into the early 1900s. Lastly, some stayed in our own homeland, living off the the land hunting, fishing, gathering, and maintaining their traditional way of life.

Colonialization and Continuation

Despite the historical trauma that had taken place during colonization, many Narragansett and other Indigenous people fought during the Revolutionary War. The most common reason for serving despite their treatment was that they believed in protecting their homeland and community. There were free Indigenous men who enlisted, and there were also enslaved Indigenous men who served in the place of their slave owner or a family member to the slave owner in exchange for their freedom after the war. To this day, Indigenous people have the highest military service per capita of all ethnicities in the United States.9From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution by Robert Geake (Author), Lorén Spears (Contributor).

Although enslaved soldiers fought in the war with the promise of freedom, many did not receive it. Slavery still existed, indentured servitude still existed, forced assimilative practices, forced education, and forced religion still existed. Such physical trauma caused psychological traumas that contributed to mental illness, depression, suicide, and disproportionate victimization from violent crimes. Also, throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, political and legal mechanisms by state and federal authorities were established in an attempt to assimilate and erase Indigenous peoples. For example, the federal Dawes Act of 1887 sought to end the traditional communal lifeways of Indigenous peoples by allotting tribal lands to individuals. Similarly, enslavement, educational policy, and the falsification of documentary records abetted those who hoped to erase the Narragansett. To formalize the erasure, the state of Rhode Island detribalized the Narragansett Tribe. The detribalization of roles, or removing people’s names from tribal membership, took place from 1880 to 1882, followed by the sale of the Indian reservation on Tuesday, July 11, 1882, at 10 AM.

Rights Regained

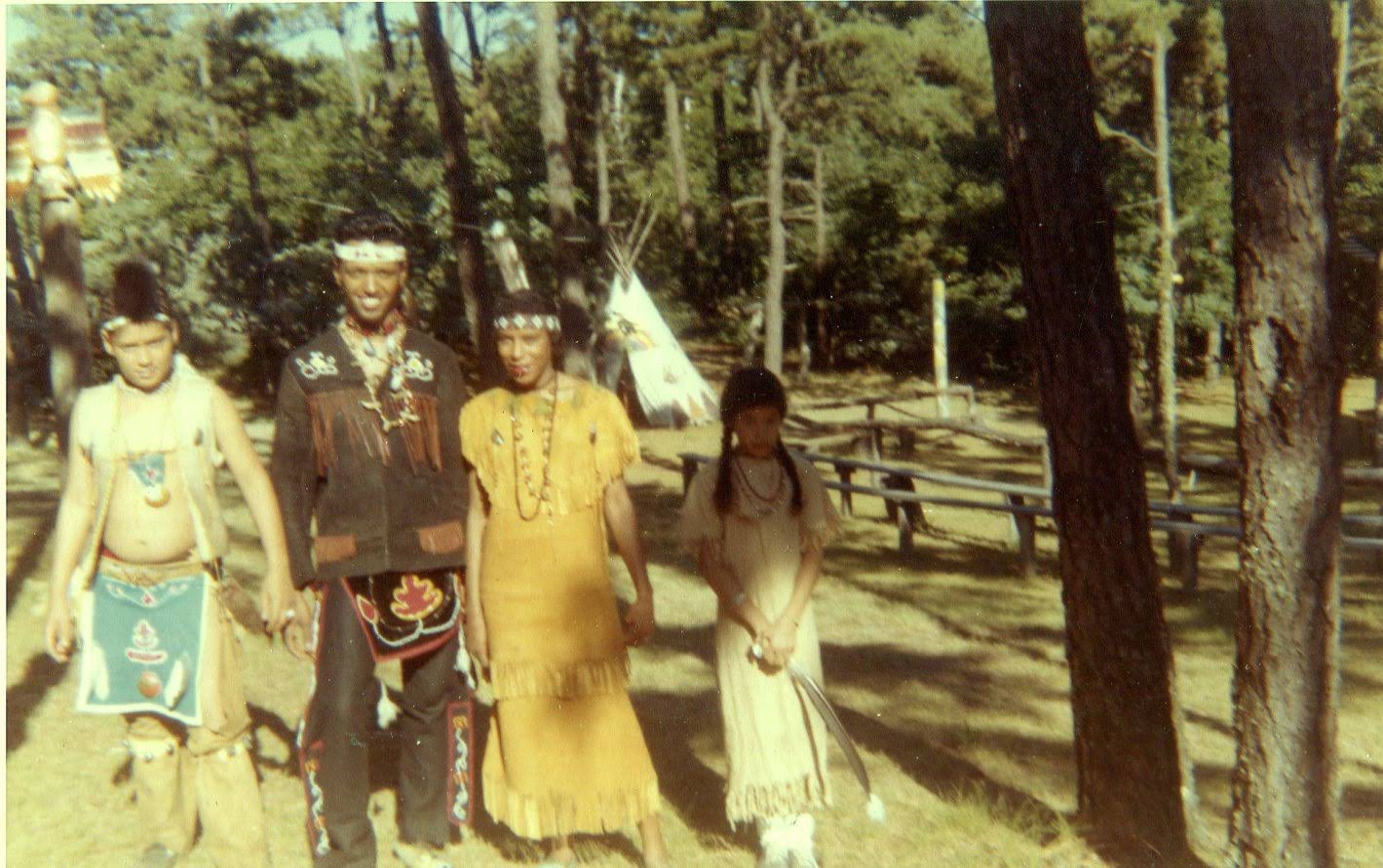

Photograph of Tall Oak and Family at August Meeting

Learn about the August Meeting Pow Wow here

In defiance of detribalization, the Narragansett and other Indigenous people continued to fight for their rights. Princess Red Wing10“Princess” is a Eurocentric term denoting royalty. However, the Indigenous population here in what became Rhode Island did not have a royal system. The governmental system was much more democratic with a council of leaders or sachems, clan leaders, and the people had a strong voice in decisions for the community. However, due to European influence, the terms prince, princess, king, and queen were adopted and often referred to a leader or chief, of which Red Wing was both. Out of respect for the time period she lived, and how I always referred to her, I still refer to her as Princess Red Wing, due to her life and legacy. Today, we have moved away from these Eurocentric terms for a variety of reasons, including decolonizing and Indigenizing our language; uplifting our language and culture by utilizing our words for chief or leader, sachem for male or saunksqua for female. was born in 1898, shortly after detribalization, and before Indigenous people had rights as citizens of this country. It wasn’t until June 2, 1924, that Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act, which granted citizenship to all Native Americans born in the U.S. This took place four years after women earned the right to vote in 1920.11For more information about the Struggle for Women’s Suffrage in Rhode Island, see our Encompass chapter [link] And it wasn’t until the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 that supported the right for Indigenous people to self-govern, supported the right for Indigenous nations to hold sovereignty, and reversed assimilative practices. However, it took until the Civil Rights Act of 1957 for all American Indians to gain the right to vote because, until then, states controlled the right to vote even after the passing of the earlier federal Citizenship Act. Still, poll taxes and intimidation at the polls kept many Indigenous people from voting until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. During this time, Princess Red Wing was an educator, activist, leader, and culture bearer. She was also the editor of the Narragansett Dawn, a newspaper that taught the history, culture, and language of the Narragansett people.12To access issues of the Narragansett Dawn please visit the DigitalCommons@URI. [link]

Through her work, Princess Redwing helped the Narragansett Tribe be visible and known to the general public during this period of detribalization and reclamation of self-governance. Despite the activism of Princess Redwing and the passing of the laws that gave Indigenous peoples more rights, there are still barriers throughout the United States that make it difficult for Indigenous people to vote. For example, polling places are sometimes located in areas that are not easily accessible for people living on Indigenous reservations. Language barriers and low literacy in some areas also make voting difficult. In 2016, the Rhode Island Secretary of State’s office approved the use of tribal ID as proof of identity at polling locations. This marked an important recognition of sovereignty and citizenship of Indigenous people here in Rhode Island. The Tomaquag Museum, which Princess Red Wing co-founded, played a role in advocating for this right to use tribal ID through its Indigenous Empowerment Network13See more about the Indigenous Empowerment Network on the Tomaquag Museum website [link]. The move to allow tribal ID is also important for those who do not have the funds or the need to purchase a state ID or driver’s license, which were initially two of the few acceptable forms of identification allowed to access voting privileges previous to this recent decision.

Although not active politically, cultural icons can symbolically break barriers and advance change even if they are not advocating for it. One such cultural icon for the Narragansett Nation was Ellison Meyers Brown14To learn more about Ellison Meyers Brown, see this article on Rhode Tour [link]. He was a marathon runner and received the nickname “Tarzan” from his family because of his athletic abilities. He won the Boston Marathon in 1936 and in 1939. He was an Olympian and went to the Olympics in Berlin, Germany in 1936. He won many marathons throughout his life. Because of this fame, like Princess Redwing, he helped make the Narragansett Indian Tribal Nation known to the general populace during the period of detribalization. It was important for the Narragansett Nation that Brown, Redwing, and other Narragansett leaders kept our culture visible in society because when it came time to advocate for our rights, we were able to gather allies and prove our continuation as a people socially, politically, economically, and culturally to state and federal governments.

When the United States Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 was passed into law to decrease federal control over American Indians and increase self-governance and responsibility, the Narragansett then incorporated. Princess Redwing created the seal that is still used today. After many decades of legal battles, the Rhode Island Land Claims Settlement Act of 1978 returned 1800 acres of land to the Narragansett Tribal Nation. That same year, the United States Indian Child Welfare Act was enacted to protect Indian children from being taken from their communities and adopted by non-native families. Children were also previously taken away and sent to government boarding schools. The last such industrial school in Rhode Island, the State Home and School for Dependent and Neglected Children, closed in 1979.15Recovering Lost Innocence: Archaeology at the State Home and School by E. Pierre Morenon In 1983, the Narragansett Tribal Nation received Federal Acknowledgment and Recognition, reasserting the trust relationship between our nation and the federal government. Today, the Narragansett continue to fight for economic, political, and cultural sovereignty and justice.

The Narragansett Tribal Nation still practices its cultural beliefs, traditions, and lifeways. Each year, the Tribe hosts the annual August Meeting Powwow, where the public can learn about our history and culture. Today, many of our community still hunt, fish, garden, and gather traditional food, medicines and materials. The Narragansett Food Sovereignty Initiative is an example of this continuation. Artists represent their cultural knowledge through creation of traditional and contemporary art forms. Youth carry on their Native ways of knowing, including language, music, dance, storytelling, history, and leadership. Each family, clan, and citizen of the Narragansett Nation contributes to the vibrancy and legacy of the First Peoples of this land we call “Nahahiganseck.”

Terms:

Symbiotic: working together

Kinship: usually refers to blood relation, but can also refer to familial ties and community ties. Kinship can be an be made through alliances that are not blood-related

Decimated: in this context, destroy a large percentage of a population of people

Compatriots: fellow countrymen

United Colonies of New England: also called the New England Confederation, the United Colonies of New England included Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Haven, and Plymoth. Rhode Island did not join the United Colonies

Genocide: the killing or decimation of a population of people usually belonging to a particular ethnic group or nation

Displacement: moving of a group of people or a community from where they are living to another place that is usually less desirable and with less resources or dispersing a people through the claiming of land

Indentured servitude: different from enslavement in the sense that the person serving had a contract that had an end date. However, some look at this as another form of slavery because owners could extend the contract for random offenses

Historical trauma: is the accumulative emotional and psychological pain over an individual’s lifespan and across generations as the result of massive group trauma (Yellow-Horse Brave Heart, 1995)

Assimilative practices: are the strategies or tools the dominant groups force upon the minority groups to force them to the dominant cultural practices

Erasure: the removal of writing, recorded material, or data. the removal of all traces of something; obliteration. The removal of all cultural, spiritual, educational, lifeways, mores, customs and traditions from a community through practice, education, ecological, religion, political, legal and other systems of oppression.

Detribalization: Remove a whole community from their social and political / governmental structure. To transform a collective political body (tribe or nation) into individuals, without the rights of tribal citizens.

Sovereignty: the ability for a community to control and maintain its own government. Federally recognized tribes are sovereign nations and have relationships with the United States government much like states do

Trust: a “trust” relationship allows each nation, as a domestic sovereign, the right to self-determination, self-regulation, economic development, and self-governance

- 1Letter to King Francis I of France from Giovanni da Verrazzano reporting his voyage to the New World [link]

- 2To learn more about these Narragansett sachems (leaders), visit the Rhode Tour article highlighting their stories. [link]

- 3To learn more about Roger Williams and his dealings with tribal nations, listen to “Roger Williams and the Pequot War” from the Public’s Radio Mosaic podcast. [link]

- 4See a transcribed copy of The Key to the Language of America on Project Gutenberg [link]

- 5See a transcribed, annotated copy of the RI Royal Charter [link]

- 6Learn more about the Pequot War [link]

- 7Learn Sarah Muchamug’s story at Rhode Tour [link]

- 8Learn more about the Brothertown Movement [link]

- 9From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution by Robert Geake (Author), Lorén Spears (Contributor).

- 10“Princess” is a Eurocentric term denoting royalty. However, the Indigenous population here in what became Rhode Island did not have a royal system. The governmental system was much more democratic with a council of leaders or sachems, clan leaders, and the people had a strong voice in decisions for the community. However, due to European influence, the terms prince, princess, king, and queen were adopted and often referred to a leader or chief, of which Red Wing was both. Out of respect for the time period she lived, and how I always referred to her, I still refer to her as Princess Red Wing, due to her life and legacy. Today, we have moved away from these Eurocentric terms for a variety of reasons, including decolonizing and Indigenizing our language; uplifting our language and culture by utilizing our words for chief or leader, sachem for male or saunksqua for female.

- 11For more information about the Struggle for Women’s Suffrage in Rhode Island, see our Encompass chapter [link]

- 12To access issues of the Narragansett Dawn please visit the DigitalCommons@URI. [link]

- 13See more about the Indigenous Empowerment Network on the Tomaquag Museum website [link]

- 14To learn more about Ellison Meyers Brown, see this article on Rhode Tour [link]

- 15Recovering Lost Innocence: Archaeology at the State Home and School by E. Pierre Morenon