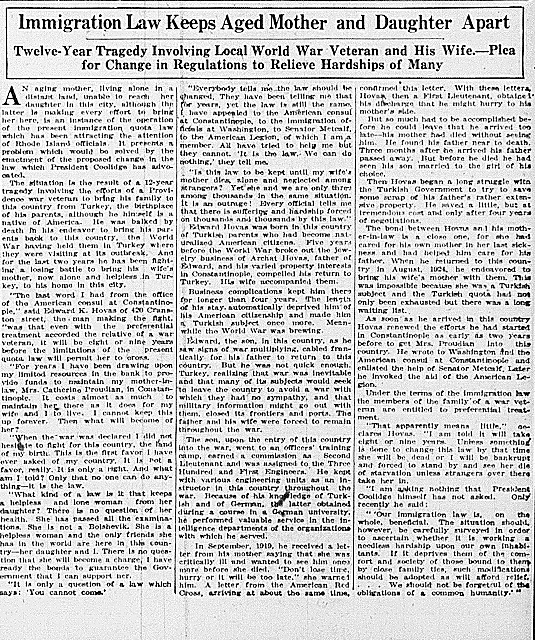

Providence Journal Article

This photo shows a 1926 story reported in the Providence Journal about a local family whose grandmother was being prevented from immigrating to the United States because of strict quotas on immigration. Immigration quotas limited the amount of people who could immigrate to the United States from certain countries due to stereotypes many Americans believed about immigrants.

The 1924 Immigration Act

Essay by Talia Brenner, Brown University Alumna

On March 7, 1926, The Providence Journal published an article about a Providence family, the Hovases, whose elderly grandmother, Kadarina Proudian, was prevented from entering the U.S. to live with them. The Hovases had moved to Providence from Constantinople, Turkey (now called Istanbul) in 1924 with their two children. Edward Hovas was born in Providence, RI, to Armenian immigrant parents but had lived abroad for many years. While abroad, he met and married Lucy, who was also Armenian. By 1926, Lucy’s mother, Kadarina Proudian, who still lived in Constantinople, wanted to move to Providence to live with Lucy and her family. Lucy and Edward, who had been sending Kadarina money to live on, also wanted her to come to Providence. The U.S. government, however, banned Kadarina from immigrating because of newly strict limits on immigration called quotas.1“Immigration Law Keeps Aged Mother and Daughter Apart,” Providence Journal, March 7, 1926, f8.

The federal government, which decides all laws relating to immigration, began setting limits on immigration in 1882 with the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned immigration from China for a period of ten years.2“Chinese Immigration and the Chinese Exclusion Acts,” Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, accessed December 30, 2019 [link] Before 1924, the government was setting quotas on how many immigrants could enter from certain countries. But the Immigration Act of 1924, also known as the Johnson-Reed Act, was even more restrictive. It banned all immigrants from Asia and set strict quotas on the number of immigrants allowed from Southern and Eastern Europe. Since Turkey was one of the countries for which the U.S. had a newer, stricter quota, Kadarina Proudian would not be allowed to immigrate to the U.S. for another eight or nine years. The Hovases knew that it was likely that Kadarina would die before she was permitted to enter the United States. Edward Hovas angrily told The Providence Journal, “Is this law to be kept until my wife’s mother dies, alone and neglected among strangers?”3“Immigration Law Keeps Aged Mother and Daughter Apart,” Providence Journal, March 7, 1926, f8.

Kadarina suffered as a result of this law, even though she was fortunate compared to other people who wanted to immigrate. She had family in the United States who were offering to take care of her. Edward was not looked down upon as an immigrant since he was born in the U.S. He was also respected because he fought for the United States in World War I. In 1919, the mayor of Providence wrote a letter to support Edward’s application for a U.S. passport.4Edward K. Hovas, U.S. Passport Application, issued 8 October 1919, certificate 126081 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration), roll 946, certificates 126000-126249 (8 Oct 1919-8 Oct 1919), microfilm. Fortunately, Kadarina was able to immigrate to the United States, but not until 1930, and Edward’s connections may have helped her move up the waiting list.5List or Manifest of Alien Passengers for the United States Immigrant Officer at Port of Arrival, S.S. Alesia, arrival 4 September 1930 (Washington, DC: National Archives, Publications of the U.S. Government), Record Group 287. We can only imagine how helpless other people who were less well-connected were affected.

Another effect of the 1924 law was in limiting the movement of people in and out of the U.S. A common misconception is that people who move to the U.S. never return to their countries of origin. In reality, many immigrants in Rhode Island, especially Italians, would travel back and forth between Italy and the U.S. to work seasonal jobs. These people were called “birds of passage” because they moved to different places for different seasons. Most birds of passage were very poor and moved around so they could get the best work possible. Italy, like Turkey, was one of the countries upon which the 1924 law placed strict quotas for immigration. For Italians, these quotas meant that they either had to stay in the U.S. or stay in Italy since it was now much tougher to go back and forth each year 6Thierry Rinaldetti, “Italian Migrants in the Atlantic Economies: From the Circular Migrations of the Birds of Passage to the Rise of a Dispersed Community,” Journal of American Ethnic History 34, no. 1 (2014): 7.

The Americans who supported the 1924 Immigration Act wanted stricter limits on immigration from Asia and Central and Southern Europe because they believed that people from these places were inferior to Northern Europeans. Many Americans believed that these “less desirable” immigrants were inferior to White Americans and immigrants from Western Europe.7“Immigration Act of 1924 Prohibits Immigration from Asia,” Equal Justice Initiative, accessed December 30, 2019 [link]

The way that American immigration officials would test newly arriving immigrants showed their suspicions about immigrants. Long before the 1924 Act, when immigrants first arrived in the United States, immigration officials would test newly arriving immigrants for their intelligence and for diseases before deciding if they should enter the United States. In Providence in 1914, newly arriving immigrants being tested for their intelligence would be asked to touch wooden cubes or pennies in a particular order. Immigration officials would ask child immigrants to count or would simply tap them on the chin and watch how they responded to see if the children were “all right.”8“Our Mental Tests for Aliens,” Providence Journal, March 15, 1914, section 5, 1. When the authorities decided that people were unfit to enter the United States, they would be forced to return home.

The Hovases knew about the suspicion of and the bias against immigrants. In 1930, the Hovases had legal trouble with their neighbor, an American-born woman, whom they said attacked the Hovas children because of her anti-immigrant beliefs.9“Families Enjoined from Molesting Each Other,” Providence Journal, July 10, 1930, 17. It is understandable why, then, that on the national census that same year, Edward and Lucy lied and said that all of their children were born in the United States, even though their two oldest children, Lydia and Roy, were actually born in Constantinople. Edward Hovas also said that both of his parents were born in the United States, even though they were actually both immigrants.10Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930), T626, 2667 rolls, microfilm. The 1924 Immigration Act was one way that discriminatory opinions made their way into law.

The 1924 Immigration Act was not repealed until 1965, and many people like Kadarina Proudian were affected by the quotas in the decades in between. For instance, many people fleeing the Holocaust in the 1930s and 1940s were not allowed to enter the United States. In 1938, the Providence Journal reported that because of quotas, it would take six years for all Jewish refugees from Austria and Poland to receive visas to enter the United States.11“3000 Jews Seek American Visas,” Providence Journal, December 8, 1938, 3. The restrictions on immigration significantly lowered the number of immigrants entering the United States in this period.

The 1924 Immigration Act was influenced by a fear of and dislike for immigrants from certain countries based on U.S. attitudes about race and ethnicity. The quotas enacted in 1924 were strict and in place for decades before they were repealed. Though the quotas were repealed in 1965, we still hear about anti-immigrant attitudes in the United States and around the world today. Can you think of examples of how anti-immigrant attitudes are revealed today?

Terms:

Quota – a set limit; the number of people from certain countries allowed to enter the U.S. under the Immigration Act of 1924

Questions:

Why do you think Americans wanted stricter quotas on immigrants in 1924? Do you think Americans support stricter immigration today? Do you think these are connected?

Why do you think the Hovases lied on the 1930 census?

Why did immigration officials test immigrants arriving in the U.S.? What beliefs were behind these tests?

How do you think the Providence Journal article about the Hovas family influenced how its readers in 1926 felt about the restrictions on immigration?

- 1“Immigration Law Keeps Aged Mother and Daughter Apart,” Providence Journal, March 7, 1926, f8.

- 2“Chinese Immigration and the Chinese Exclusion Acts,” Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, accessed December 30, 2019 [link]

- 3“Immigration Law Keeps Aged Mother and Daughter Apart,” Providence Journal, March 7, 1926, f8.

- 4Edward K. Hovas, U.S. Passport Application, issued 8 October 1919, certificate 126081 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration), roll 946, certificates 126000-126249 (8 Oct 1919-8 Oct 1919), microfilm.

- 5List or Manifest of Alien Passengers for the United States Immigrant Officer at Port of Arrival, S.S. Alesia, arrival 4 September 1930 (Washington, DC: National Archives, Publications of the U.S. Government), Record Group 287.

- 6Thierry Rinaldetti, “Italian Migrants in the Atlantic Economies: From the Circular Migrations of the Birds of Passage to the Rise of a Dispersed Community,” Journal of American Ethnic History 34, no. 1 (2014): 7.

- 7“Immigration Act of 1924 Prohibits Immigration from Asia,” Equal Justice Initiative, accessed December 30, 2019 [link]

- 8“Our Mental Tests for Aliens,” Providence Journal, March 15, 1914, section 5, 1.

- 9“Families Enjoined from Molesting Each Other,” Providence Journal, July 10, 1930, 17.

- 10Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930), T626, 2667 rolls, microfilm.

- 11“3000 Jews Seek American Visas,” Providence Journal, December 8, 1938, 3.