Harry Fearson and Black Baseball

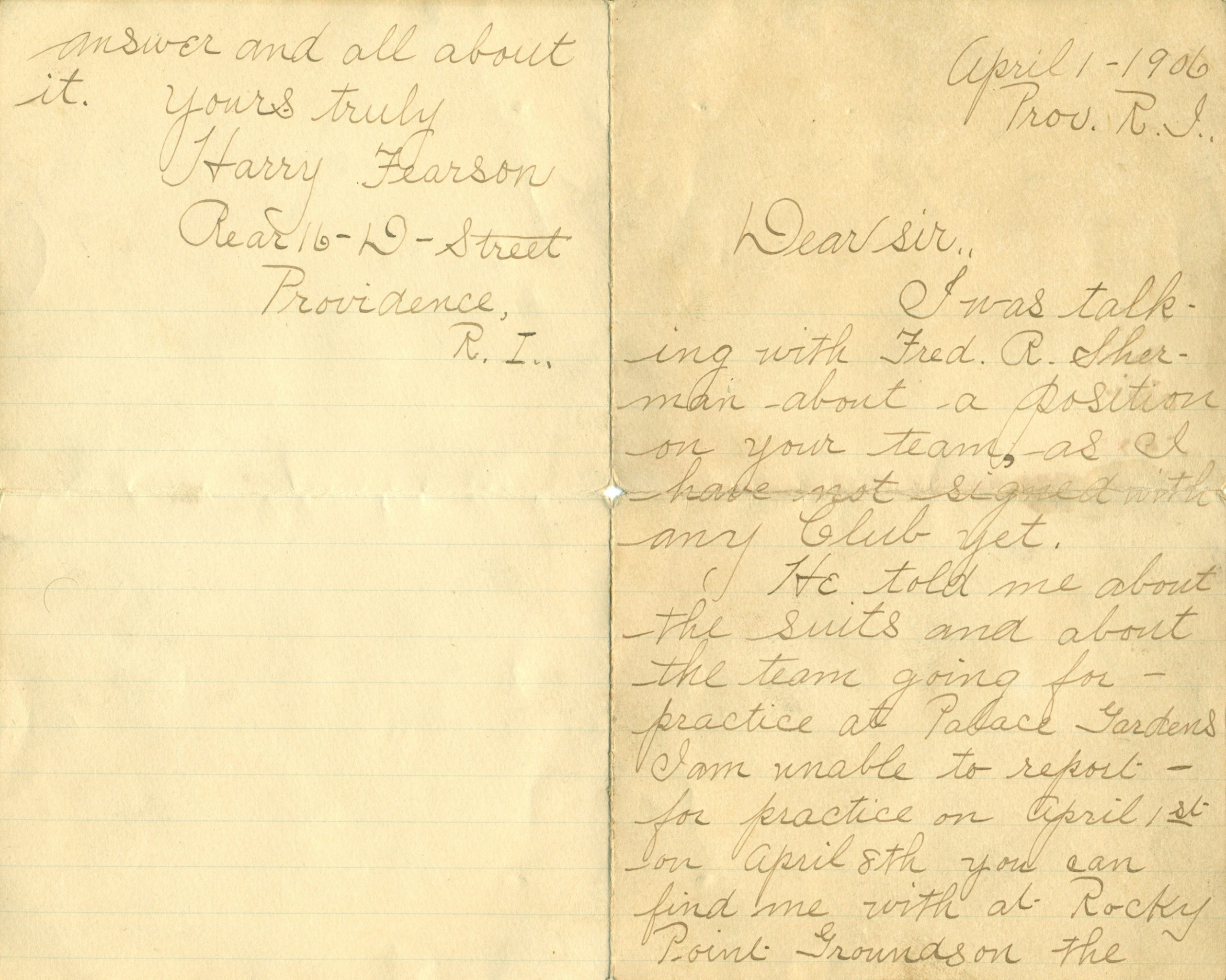

Harry Fearson’s letter demonstrates the relationship between sport and racial integration. Written in 1906, Fearson, an African American baseball player, inquired about participating on the Suits, a white team owned by Ralph Lockwood in Warwick. The letter signified the absence of a tightly drawn color line in local baseball. Fearson’s career included participation on white and Black teams including Daniel Whitehead’s Providence Colored Giants from 1905-1911.

[Click here for the full letter and transcription]

Black Baseball in Rhode Island

Essay by Robert Cvornyek, Professor Emeritus of History, Rhode Island College

Many African Americans shared a common bond with sports that paralleled their broader experiences in American society. This bond encouraged historians to interpret the connection between sport and race as a promising means to explore America’s racial past. During the Jim Crow era, baseball, the national pastime, reflected societal attitudes and practices that excluded African Americans from full participation in American life. Once Major League Baseball endorsed this racial mindset, Black players created leagues of their own to challenge the prevailing construction of race.

While our understanding of the professional Negro Leagues (1920-1960) has grown significantly during the past decade, the same cannot be said for local and regional teams that competed at the amateur and semi-professional level. We know less about the intimate relationship between “Blackball” and the neighborhoods that supported their players. Rhode Island never hosted a team in the Negro Leagues, the state’s blackball reputation rested elsewhere. In cities like Providence and Newport, Black baseball was a local game with hometown heroes. Players, promoters, and fans fueled the cultural and social vitality of their communities. Together, they encouraged African Americans to negotiate the boundaries of racial identity, create viable businesses, and clear the path for integration.

Several of Rhode Island’s earliest Black baseball teams showcased their talent during Emancipation Day, the community’s premiere cultural event. Thousands traveled to Rocky Point in Warwick to commemorate the abolition of West Indian, not American, slavery. By the late 19th century, the “unofficial” championship of Rhode Island Black baseball, and sometimes for all New England, was contested on August 1 as part of the annual celebration.1Robert Cvornyek, “Touching Base: Race, Sport, and Community in Newport,” Newport History (Winter, 2016), 1-2

Onlookers lined the Rocky Point midway to watch the best teams square off against one another. In 1883, the Newports defeated the Providence Whackers by a score of 7-6 to claim the state’s first championship trophy. By 1886, Providence retaliated and won its first title by a tally of 11 to 6. A competitive rivalry existed between the cities until the turn of the 20th century. Thereafter, games featured teams from Providence that sought city-wide championships.2Cvornyek, “Touching Base,” 2

Emancipation Day games attracted the single largest crowds, but baseball enthusiasts, both Black and White, knew that the best African American players resided at coastal hotels, especially in Watch Hill. Each summer, African American men left the South for seasonal employment as waiters in Rhode Island’s major resorts. Many waiters were seasoned baseball veterans who returned yearly to represent the Watch Hill House, Ocean House, and Larkin House. These men serviced tables, but also provided musical, theatrical, and athletic entertainment. According to historian James Brunson, waiters symbolized the “melding of black ball and black cultural production.”3James E. Brunson, “Hotel Resorts and the Emergence of the Black Baseball Professional: Riverine and Maritime Communities” in Todd Peterson, The Negro Leagues were Major Leagues: Historians Reappraise Black Baseball (Jefferson: McFarland, 2020), X

In 1888, the Springfield Daily Republican reported that the waiter’s team at the Watch Hill House “has been invincible for several seasons.”4Springfield Daily Republican, June 24, 1888, 5 The team’s roster regularly included professional Black players like Alfred Jupiter and William Selden. Both men previously pitched for the Cuban Giants, the first independent Black professional team.5Watch Hill Surf, August 3, 1888, 1 and August 21, 1888, 1. See also, Watch Hill Life, July 14, 1900, 1 Hotel guests contributed to an athletic fund that provided uniforms and trophies in support of their respective teams. The best players, however, received a purse of $25 and bonuses of $1 for “three baggers” or “sensational slides.”6Springfield Daily Republican, June 24, 1888, 5 The hotel circuit lasted until into the 20th century and ended during World War I.

Individual players made money based on their performance, but the commercialization of Black baseball as a financial enterprise occurred in Providence. In 1904, Daniel “Big Dan” Whitehead migrated to Providence from Savannah, Georgia. A year later, he created the Providence Colored Giants and legally incorporated the team with Rhode Island’s Secretary of State. He scheduled games at Melrose Park, an enclosed stadium where fans purchased tickets at the gate. Whitehead promised a team of local and regional ballplayers worth “the price of admission.” The Colored Giants opened their 1905 season before 1700 paying fans. A new era had begun.7Robert Cvornyek and Fran Leazes, “The Price of Admission: Daddy Black, Big Dan Whitehead, and the Money Game,” Rhode Island History (Winter/Spring, 2020), 54

Whitehead’s teams became more successful during the 1920s. Kinsley Park, the city’s largest sporting venue, now hosted Black baseball games. Whitehead’s financial achievement attracted the attention of White teams eager to split gate receipts. The money-making potential of Black baseball drove a wedge into the racial segregation that defined the sport’s earlier history. Another new era had begun. In May 1926, the Giants joined the previously all-White Suburban League. A month later, Whitehead added a few White players to his team. A Black team that integrated with White players disrupted the traditional Jackie Robinson narrative and refocused attention on the distinctive experiences of the local game.8Cvornyek and Leazes, “The Price of Admission,” 57

Despite Whithead’s accomplishments, he never delivered a truly professional team to Rhode Island. He lacked connections to arrange games with professional clubs and financial reserves to guarantee his players a fixed weekly salary. The one person who could elevate the local game to that level was Arthur Black. By 1931, Arthur “Daddy” Black had accumulated a small fortune as the “Lottery King” of Providence. He controlled an illegal gambling operation in Hoyle Square known as The Numbers. Individuals picked three numbers with the hope that their selection matched a random draw. When someone hit the lottery, the payoff was 600-1. Most lost their bet and their wager landed in Black’s pocket.9Cvornyek and Leazes, “The Price of Admission,” 53

Black was no stranger to baseball. In 1924, he partnered with the White owners of the Rhode Island based Cleveland Colored Giants. Years later, he became the sole owner of the Monarchs, a White team that hailed from Providence’s West Side. He reached the peak of his baseball career in 1931 when he purchased and reorganized Whitehead’s Providence Colored Giants. Black knew that the arrival of the Great Depression resulted in the demise of the National Negro League and that professional Black players were looking for work. Black signed several former Negro Leaguers and arranged for his team to travel to New York City to play the Harlem Stars at the Polo Grounds. The Giants lost both ends of a doubleheader. The team failed to meet Black’s expectations and he walked away from the game at the end of the 1931 season.10Cvornyek and Leazes, “The Price of Admission,” 56-57

In 1932, the Colored Giants returned to Whitehead with disastrous results. The players fully expected weekly salaries, but soon realized that they would split gate receipts. This arrangement proved unacceptable, and players left town in search of more lucrative contracts. Whitehead told his friends that he was through with baseball forever. Both Whitehead and Black died in 1932, and their deaths ended an important chapter in Rhode Island Black baseball. Black fell victim to gunshot wounds suffered at the hands of rival gangsters. Whitehead succumbed to a heart attack.11Cvornyek and Leazes, “The Price of Admission,” 58

During the difficult decades of depression and war, baseball provided a sense of community for many African Americans. Black baseball in Rhode Island returned to its local roots. In 1932, Newport’s Union Athletic Club became the only Black team in the city’s Municipal League. The club’s superb performance resulted in an invitation to join Newport’s prestigious Sunset League.12Cvornyek, “Touching Base,” 7 In Providence William “Dixie” Matthews, former multi-sport athlete at Providence College, organized the All-Stars, a team that introduced party politics into sport.13“Matthews to Lead Baseball Team,” Providence Journal, July 4, 1933, 19 and “Athlete Dixie Matthews Dies; Former City Official,” Providence Journal May 15, 1981, C3 Matthews represented a new generation of African Americans that pledged its loyalty to the Democratic Party and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Matthew’s roles as Democratic Ward Boss and baseball promoter collided when he staged games that endorsed candidates and recruited members for the Democratic Party. Baseball revealed the political realignment that occurred among Rhode Island African Americans during the Depression.

Baseball’s role in the community strengthened when the John Hope Community Association issued its founding Articles of Incorporation in 1939. The Association constituted itself to maintain and further the civic, cultural, and recreational interests of the community. As part of its endeavor, the Association created a baseball league that included teams from Fox Point, Pratt Street, Coddington Court, and Elmwood Avenue. In 1943, the Quonset Colored Sailors entered the league with outstanding players from around the country. At the end of the season, the John Hope League champion challenged Providence’s top-ranked independent ball club for city-wide bragging rights.14Robert Cornyek, “Jimmy Lewis and Black Baseball in Rhode Island,” Providence Journal, June 7, 2008, F3

Following World War II, many former players returned home from Europe and formed one of Rhode Island’s most outstanding teams, the Invaders. In 1945, the best Black ballplayers in Providence formed the Invaders Baseball Club, which quickly became New England’s most successful African American semi-professional team. These players competed against prominent regional clubs, both Black and White, including the powerful Boston Colored Giants. The Invaders also hosted hard-hitting barnstorming clubs like the Philadelphia All-Stars and Washington Pilots with rosters that listed former professional Negro League players. Fans packed Pierce Memorial Stadium in East Providence to demonstrate their appreciation for the team and its owner, Richard “Pop” Dudley, for the pride and sense of accomplishment the Invaders exemplified. The team ended its short, but remarkable run in 1948 as the last Black team in Rhode Island.15Robert Cvornyek, “Providence’s Summer of ’49, Integrating Baseball Its Way,” Providence Journal, July 18, 2010, C 11

In 1949, several of the Invaders joined the state’s first truly integrated ball club. Jackie Robinson already desegregated Major League Baseball with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947 and its historic importance reverberated in Rhode Island. Ernest “Biffo” Duarte, a sports promoter and ex-boxer from Fox Point, scouted Rhode Island’s best players, Black and White, to create the finest team around. He named the team the Circle Athletic Club because nothing was more complete than a circle. Duarte petitioned for admission into Providence’s Tim O’Neil Amateur League, and his team achieved first-place in its inaugural season. For the African American community, the Circle club’s championship trophy signified the promise of integration and racial equality.16Cvornyek, “Providence’s Summer of ’49,” C11

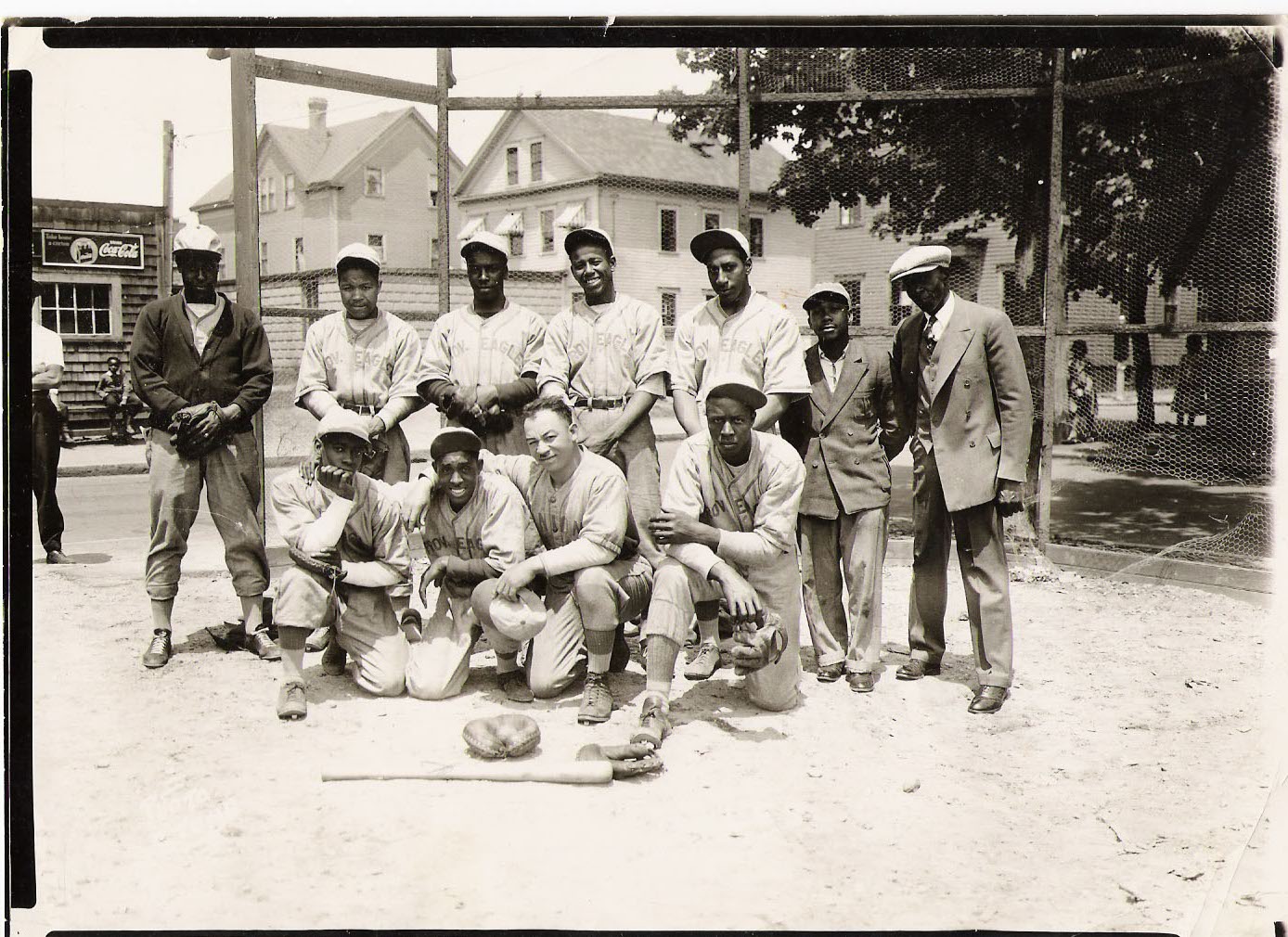

Charles Butler, the Circle’s star pitcher, personified the end of Black baseball and the transition to integration. Butler began his baseball career in the John Hope League and later accepted an offer to play for Red Smith’s Providence Eagles. Following a distinguished career in the military during World War II, Butler pitched for the Invaders and ended his career with the Circle Club in 1951.17Cvornyek, “Providence’s Summer of ’49,” C 11

The integration of local baseball proved a bittersweet moment. In 1955, Vinnie Brown, sportswriter for the Providence Chronicle, summarized this sentiment when he reported that many African Americans still longed for the “old spring and summer days when you would find a baseball game on the docket at least once a week and always on a Sunday afternoon.” He recalled games that “used to be held at Hope Field…teams that Red Smith used to field and also the Invaders.”18Vinnie Brown, “Sportin’ Round, Providence Chronicle, June 11, 1955, 2 Brown’s belief that integration denied the Black community an important cultural and social institution offered an alternative view to the triumph of integration. As historians unravel the history of local Black baseball, they must ask themselves an important question. Did African Americans surrender a sense of cultural identity and economic self-determination in their bargain for integration?

Terms:

Blackball: a term that was used at the time to refer to Black baseball. It also sometimes appears as two words – Black ball.

Emancipation Day: an African American holiday celebrated on August 1 that commemorated the abolition of slavery in the West Indies in 1834. African Americans in Rhode Island acknowledged their West Indian legacy and preferred this day rather than January 1. Most African Americans during the late 19th and early 20th century recognized January 1, the date President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation went into effect in 1863.

Hotel Circuit: a Black baseball league that consisted of hotels at a summer resort. In the Circuit, Black waiters from the hotels played against each other. The Circuit did not include games against guests, town teams, and visiting sailors stationed in the area.

Enclosed Stadium: a stadium that featured a gate for paid entry and wall to keep spectators from viewing the game for free. The enclosed stadium separated the amateur leagues from the semi-professional and professional leagues.

The Numbers: an illegal lottery game run by a number’s banker that employed runners to collect bets on the daily outcome of a random selection of numbers. The game is also known as the Lottery.

Ward Boss: a person responsible for turning out the vote, usually in an ethnic or racial neighborhood.

Providence Chronicle: an African American newspaper that covered news, sports, and entertainment in Providence and throughout Rhode Island.

Questions:

How does sport reflect and reinforce American history and life? Does it possess the potential to change race relations?

What do you think historian James Brunson meant when he stated that Black waiters were “melding” Black baseball with other forms of culture? Do you believe that baseball is a form of expressive culture like music, dance, and theater?

During the 1920s, do you believe the profit motive encouraged the racial integration of local sports?

Why did sportswriter Vinnie Brown report that African Americans lamented the end of Black baseball? What did Black communities lose during the process of integration?

- 1Robert Cvornyek, “Touching Base: Race, Sport, and Community in Newport,” Newport History (Winter, 2016), 1-2

- 2Cvornyek, “Touching Base,” 2

- 3James E. Brunson, “Hotel Resorts and the Emergence of the Black Baseball Professional: Riverine and Maritime Communities” in Todd Peterson, The Negro Leagues were Major Leagues: Historians Reappraise Black Baseball (Jefferson: McFarland, 2020), X

- 4Springfield Daily Republican, June 24, 1888, 5

- 5Watch Hill Surf, August 3, 1888, 1 and August 21, 1888, 1. See also, Watch Hill Life, July 14, 1900, 1

- 6Springfield Daily Republican, June 24, 1888, 5

- 7Robert Cvornyek and Fran Leazes, “The Price of Admission: Daddy Black, Big Dan Whitehead, and the Money Game,” Rhode Island History (Winter/Spring, 2020), 54

- 8Cvornyek and Leazes, “The Price of Admission,” 57

- 9Cvornyek and Leazes, “The Price of Admission,” 53

- 10Cvornyek and Leazes, “The Price of Admission,” 56-57

- 11Cvornyek and Leazes, “The Price of Admission,” 58

- 12Cvornyek, “Touching Base,” 7

- 13“Matthews to Lead Baseball Team,” Providence Journal, July 4, 1933, 19 and “Athlete Dixie Matthews Dies; Former City Official,” Providence Journal May 15, 1981, C3

- 14Robert Cornyek, “Jimmy Lewis and Black Baseball in Rhode Island,” Providence Journal, June 7, 2008, F3

- 15Robert Cvornyek, “Providence’s Summer of ’49, Integrating Baseball Its Way,” Providence Journal, July 18, 2010, C 11

- 16Cvornyek, “Providence’s Summer of ’49,” C11

- 17Cvornyek, “Providence’s Summer of ’49,” C 11

- 18Vinnie Brown, “Sportin’ Round, Providence Chronicle, June 11, 1955, 2