How to grow rose trees.

Whittaker, Clara. "How to grow rose trees." Independent (1848) 94, no. 3626

(June 1, 1918): 373.

[https://library-projects.providence.edu/rosarium/view?docId=tei/rg0159.xml]

That you can grow your own roses from cuttings is a fact becoming generally known in our United States; that you can raise coveted large rose trees seems to be a fact unperceived save by a few rosarians.

I have for five years proved, to the satisfaction of neighbors and gardeners, that rose tree growing can be carried on, not only by myself, but by any one who successfully grows green things. When I had discovered this fact by carefully observing the growth of one of my Paul Neyron roses, I immediately set to work growing other varieties in tree shape. At present I feel prepared to undertake the growing of about fifty varieties on their own roots in the California climate and at least a dozen hardy varieties in Eastern states. To raise your own rose trees means economy, for at the nurseries you must pay from $1 to $1.50 for each one.

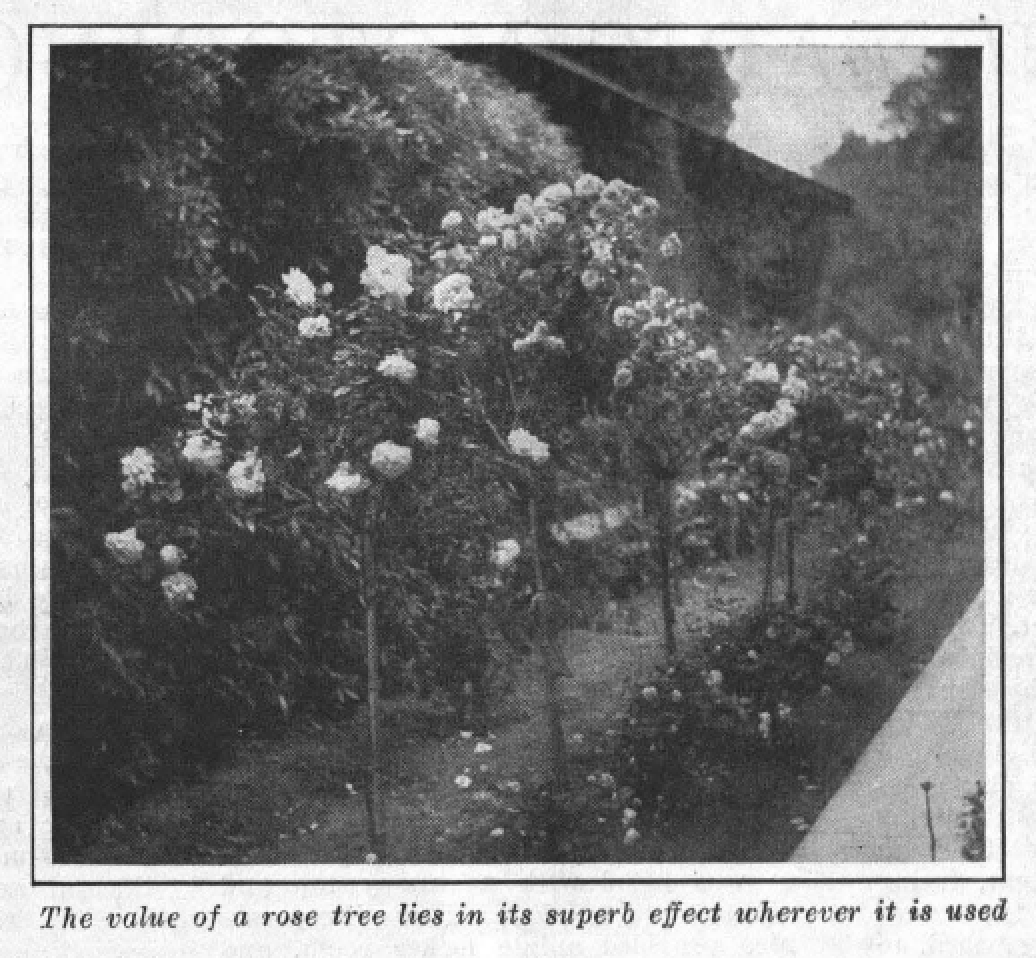

The value of rose trees, or standard roses as they are called in England, where the custom of growing them originated, lies first in the superb effect that they produce when planted by twos before the house, or singly among shrubbery and perennials, or in stately avenue effect along the sides of a walk.

Secondly, in the ease with which one can move about them, dig around them or look admiringly upon them. Rose trees occupy little ground-space, they are not in the way of lawn mowers nor do they tear the pedestrian’s clothes as rose bushes are apt to.

In landscape gardening the rose tree has come into its own, as it is particularly valuable for furnishing the straight lines and perfectly balanced effect of formal gardens. No other flower has such rare, intrinsic beauty as the rose. Yet, when grown only on low bushes as the Teas or Hybrid Teas commonly are, it is impossible for one to fully appreciate the grandeur of the blooms. On rose trees, however, they grow like a large bouquet, within easy reach.

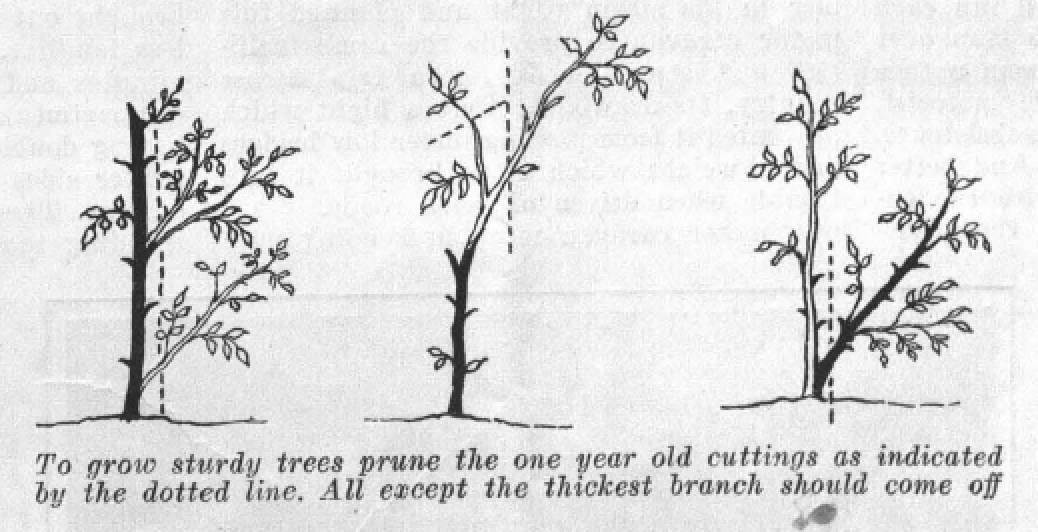

The instructions for growing a rose tree are simple but important. Two things are absolutely essential—a stout, straight, long stake and a very young rose bush. Besides these, an unlimited amount of vigilance should be practically applied. In other words it’s all in the pruning or training. A vigorous, quick-growing rose like Francois Levet, Frau Karl Druschki, Paul Neyron, or Maman Cochet, the last either pink, red or white, is best for the purpose. In spring to summer, when your rose bush or self-raised cutting is almost a year old and well rooted, trim off all branches or shoots except one, the thickest and sturdiest. It should be thick from the ground up and straight. Allow it to grow in a perpendicular line without twisting or bending. Set a stake close to it and tie it at several points. This will keep the rose straight without further effort as well as safe from storms.

For a year or so you have nothing to so, besides soil cultivation, except to rub off the "eyes," or leaf-buds, that appear on the sides of your tree trunk. Just one leafing-out bud on top should remain. All others must be removed or they will form branches. There comes a perplexing time when what looks like an infant leaf turns into a blossom. As soon as you have discovered this, carefully rub it off, or break it off. Then allow a new leaf-shoot to start where the blossom was, to elongate the cane till it is four feet high or more.

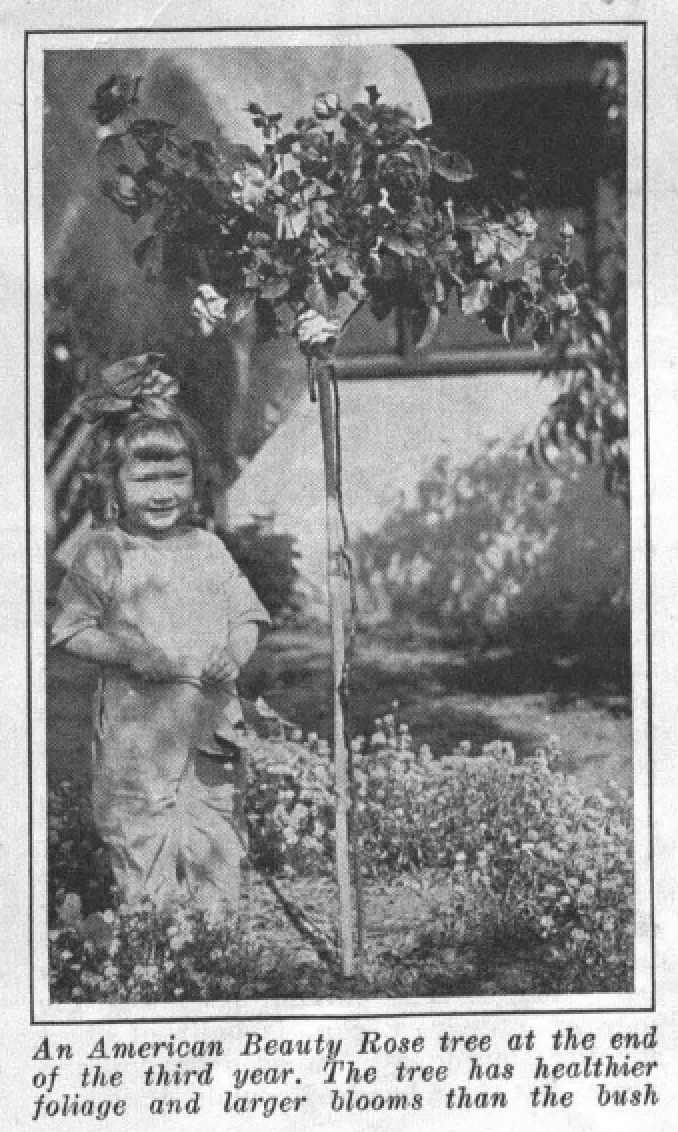

It will reach that hight in about two years if it grows in a climate like southern California’s. At that stage allow four or five eyes to remain near the top of the cane. These will soon grow lateral branches and form the crown of the rose bush.

When pruning the top, in spring, always thin out to four, five or six main branches. There you have your tree. Remove all suckers that spring up from the ground. If you neglect this for a year or more the trees will revert to a common rose bush.

There are queer notions afloat as to what constitutes a rose tree. An innocent old lady who had heard of my success wrote to me: "I have many rose bushes, but I would like to have a rose tree. Please send me a slip from yours."

Years ago, some friends of mine bought two beautiful La France rose trees. One day, when they saw that a shoot had sprung up from the ground, about one foot away from the rose tree, they decided to let it remain. Then they would have three rose trees, so they conjectured.

Alas! tho it had formed strong roots and stood transplanting well, it was and always remained an ordinary rose bush.

If you happen to live in a cold climate you cannot have a Cafrano or La France rose tree unless you box it up in winter.

But you can have in rose tree shape a dozen beautiful hardy or hardy perpetual varieties. These you can winter without protection by simply untying the tree from the stake and laying it on the ground with the crown end fastened down securely.

As a rule, you will have larger blooms and healthier foliage in a rose tree than in a rose bush or climber, because more strength is stored up in a small crown than in a spreading bush and because the air can circulate around it better. If mildew, or rust-spot should develop to can be overcome more readily because there are fewer leaves to doctor.

Better than a scraggly rose bush with its blossoms dragging on muddy soil is a rose tree with a dozen, or score, of large blooms that display their beauty even from a distance.

The perfect outline of the rose tree, free of all unnecessary branches and foliage, is a pleasure not only to the owner but to the passerby who views it from the street. Like sentinels these trees stand, seeming to guard the grounds from all intrusion of disorder.