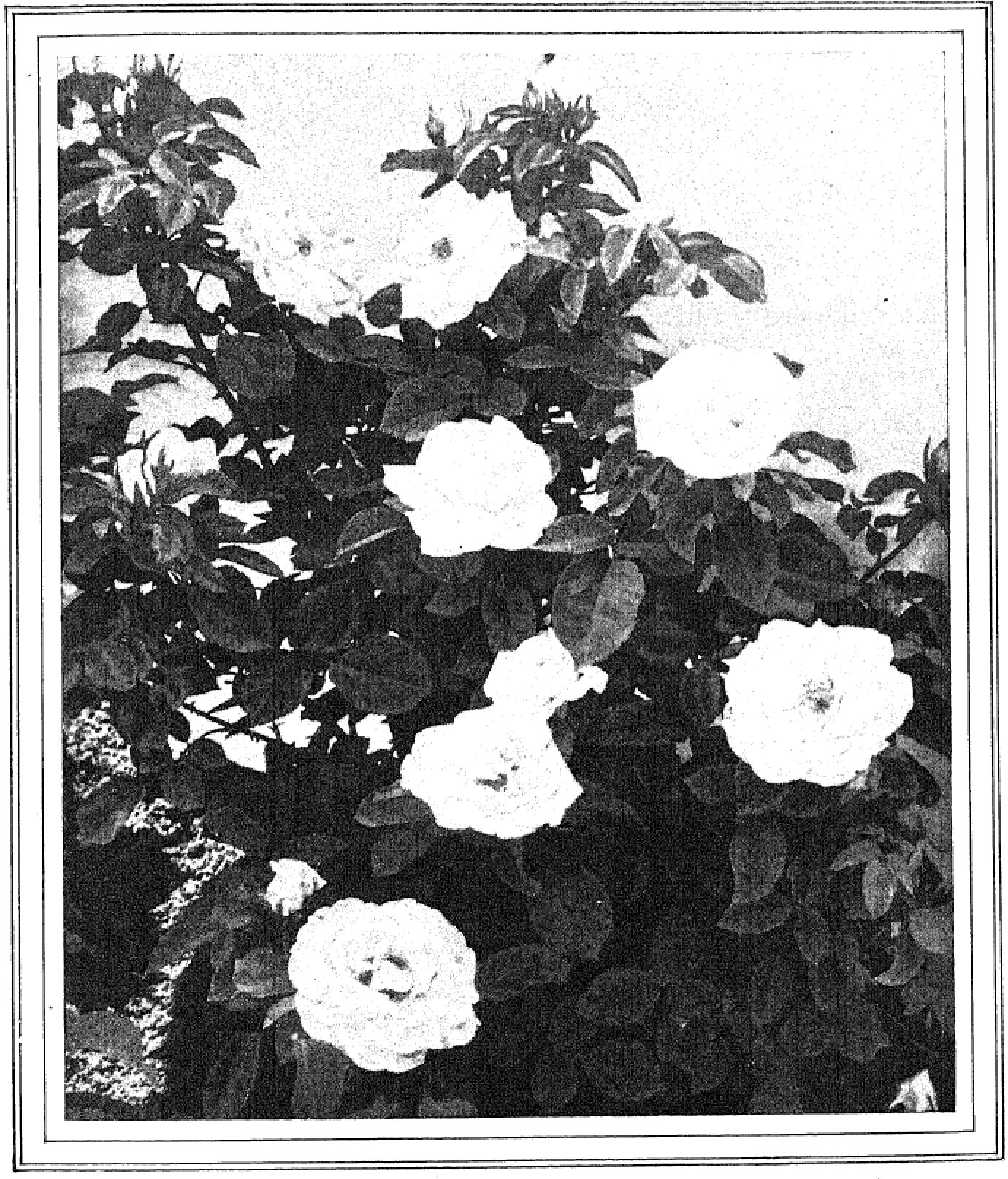

The queen of the garden.

Waugh, Frank Albert. "The queen of the garden." Womans Home Companion 41, no. 7?

(July 1914): 13.

[https://library-projects.providence.edu/rosarium/view?docId=tei/rg0154.xml]

Growing roses—It’s all in the know-how

June is the month of roses; and, partly from poetic prejudice and partly from the deep nature of the case, we feel that when that hour strikes the garden must have some roses with which to greet us. There is nothing else quite takes their place. They are superlatively refined and lovely, filled with the poetry of all times, suggesting the glorious days of chivalry, the Oriental mysteries of Harun-al-Raschid—in fact, everything rich and romantic which by any chance has ever found lodgment in one’s imagination. Decidedly the rose is the Queen of Flowers.

And yet! In our day and country we are forced to stay our enthusiasm. In the Central and Northeastern states and in the Southeastern provinces of Canada, where live a large proportion of those independent and cultivated citizens who would fain grow roses, in those wide regions the Queen of the Garden refuses her traditional favors or yields them grudgingly to him who woos most long and ardently. In plain English, roses do not seem to succeed in our neighborhood, or, if we do gain a qualified success, it is at the expense of great planning and labor.

Every principle of philosophy and horticulture admonishes us that we must Americanize our rose gardening. It suggests that the reason for our partial failures has usually been that we were cultivating French varieties after English methods in a Saharan climate under a Republican administration in Kansas. Yet all the while thousands of native roses, by nature perfectly adapted to the climate and politics of that versatile state, smile up at the deep blue Kansas sky.

Wayside blossoms

Think of the wild wayside roses found in every inhabited region of the continent! They are very different from La France and Maréchal Neil, to be sure; but are they not extremely beautiful? In their own character they are unsurpassed. There are ten or a dozen of these native species, every one of which can be successfully transplanted to the garden. And besides the aboriginal native species of the plains and woodsides we have no small wealth of genuinely American horticultural varieties. There is the Crimson Rambler. Could anything be more American, more robust, hardy, or self-sufficient, or make itself more at home on the front porch or over the door of the garage? Then there is its more modest sister, Dorothy Perkins, less strenuous but equally American. Honestly now, who would exchange either one of this pair for the fairest and finest tea rose that ever drooped its frail head in the courts of a Persian palace? Further than these we have such American hybrids as the Sargent and the Dawson roses, with several others of their groups. These too are gorgeous and prolific garden plants, which fully make up in luxuriance and in the delicate beauty of their blossoms the little they may lack in fragrance or substance of bud and bloom.

Roses are fastidious gourmets

However, it is not the purpose of this brief essay to discourage the cultivation of roses, even of the finest tea roses. Quite the contrary. And while the principle argued above holds,—that interest ought to be turned more to native hardy sorts—nevertheless much can be done by devoted amateurs in the growing of roses anywhere within the pale of civilization. A dry sandy soil is the most serious impediment; but even that can be overcome if one can stand the expense of hauling in some cartloads of clay. A proper soil is a deep, rich, well-drained loam, but a preponderance of good clay will not hurt. For a small rose bed it is possible to provide artificial drainage if necessary, and to make up a mixture of soils exactly suited to the appetites of these fastidious gourmets.

Next in order comes the question of buying plants. Roses for garden use are propagated by two principal methods: (a) cuttings, (b) budding. Some roses growers insist on budded plants, some on plants from cuttings. As nearly as we can come to a general principle is to say that some varieties succeed better by one method, some by the other. Thoroughly reliable nurserymen will usually advise the amateur when he orders his rose plants and will gladly give him the benefit of their experience.

Play trumps in spring planting

In the Southern states where roses are successfully grown winter planting is the best practice. In the Northeastern and Central states where rose growing is more difficult, early spring planting is usually recommended. It should follow the good old rule for playing trumps, i.e. when in doubt plant in the spring. Under favorable circumstances, however, fall planting is quite as good and, indeed, sometimes much better. Where hardy varieties are being put out under thoroughly favorable conditions fall planting is decidedly preferable. If the varieties are tender or only half hardy, or if any conditions are in the least unpropitious, spring planting had better be practiced.

As soon as the roses are safely growing in the garden they will begin to require some plant food. It is good practice to dress the ground heavily with barnyard manure late in the fall. As soon as the soil dries in April this fertilizer can be worked in with a fork; and this may be regarded as the best practical means of fertilizing, for the amateur. Any further shortage should be made up from good high-grade ready-made garden fertilizer. Use enough of it, about one pound to every ten square feet. This should be evenly strewn on the surface of the ground the latter part of April. Rain and cultivation will soon put it within reach of the feeding rootlets.

Prune and protect

There is room for the exercise of much skill in the pruning of the tea and hybrid perpetual roses, and this is where experience counts. At the same time the art is not so difficult but that an intelligent amateur may operate with practical success. The general rule is to prune early every spring, cutting back the weak-growing sorts distinctly closer that the strong ones. The more vigorous hybrid perpetuals should have all two-year old wood removed, all weak shoots taken out, four or five strong year-old canes being left, and these being headed back to three feet. The weaker varieties will be cut back to four or five buds on each cane. If a few large blossoms are preferred to many small ones the pruning will be more severe than if the opposite preference prevails.

One of the most necessary, and yet one of the most unwelcome practices in growing tender roses, is that of putting them away for winter. In the climate of our Northeastern states this truly has to be done. A common method is to wrap the plants in straw or burlap jackets, leaving them to stand sentinel through the snows in the deserted garden. Under many conditions it will be better to bend the canes down to the ground, fasten them with a peg and cover them over with straw and pine boughs. If they are cut back with sufficient severity at the opening of spring it will not be necessary to right them up by tying to stakes.

The varieties everyone wants

The list of varieties of roses is interminable. It would be easy from the catalogues to make up a collection of two thousand varieties. Of course no one wants so many as that. There are a few beautiful sorts which everyone desires to grow and most of which are approved by years of success. The best of all the white roses is undoubtedly Frau Karl Druschki. It is thrifty, hardy and bears grand large semi-double blossoms. Next to this the best white rose is probably Mme. Plantier. Among pink roses we may place Kaiserin Augusta Victoria at the head, followed by Magna Charta, Mme. Caroline Testout, Mrs. John Laing, Paul Neyron and President Carnot. The favorite red rose is undoubtedly General Jacqueminot, but other good red sorts are Gruss au Teplitz, Alfred Colomb, Anne de Diesbach, Killarney, Ulrich Brunner, and Camille de Rohan.

The highly condensed quality of this list is shown by the report of Mr. Theodore Wirth, superintendent of the Minneapolis parks, who, in reply to my questions, sends me a list of varieties which have succeeded in that cold and somewhat unpropitious climate. His list numbers fifty-eight hybrid remontants, thirty-five hybrid teas, thirteen polyanthas, thirty-four climbers, sixteen hybrid sweetbriers, fifteen hybrid rugosas. A few of the commoner sorts which have been approved in this list (and not already mentioned above) are Marchioness of Dufferin, Marshall P. Wilder, Fisher Holmes, Marchioness of Londonderry, Baron de Bonstettin, Maman Cochet, La France, Richmond, My Maryland, Mrs. Aaron Ward, Clothilde Soupert.

Although the great value of the hardy, shrubby species of roses has already been emphasized, this matter is of so much importance that we may well come back to it, in order to show how this forms the connecting link between rose-growing and the usual kinds of native gardening. Perhaps the characteristic feature of the American landscape gardening in recent years has been its lavish use of hardy shrubbery. There is a great deal to be said, especially under the conditions offered by American climate, in favor of hardy shrubs for garden decoration. Certainly on most private and public places the extended use of shrubbery is more than justified.

This all comes to its application in the present discussion from the fact that we have at our hand a large number of most admirable species and varieties of hardy roses which take their places in the shrubbery borders to everybody’s utmost satisfaction. Indeed there are no finer shrubs of any sort than some of these hardy roses.

The best hardy roses

Several of the best of these shrub roses are native American species—the wild roses of pastures and roadsides. Amongst these we may particularly notice the meadow rose (R. blanda), the very hardy self-sufficient Carolina rose (R. carolina) and the little pasture rose (R. nitida). But the best of all this lot is the wonderful prairie rose (R. setigera), native to the prairies and thickets from Ontario to Florida, but more especially characteristic of the region of the Great Lakes. This is the finest of the hardy sorts, one of the latest and most profuse in blossom and one of the easiest to propagate.

Besides these strictly native American species there are several imported wild roses “just as good.” Of these we may mention the old white cottage garden rose (R. alba); the Alpine rose (R. alpina); the Provence rose (R. gallica); the splendid many-flowered Japanese climbing rose (R. multiflora); the poet’s favorite Eglantine or Sweetbrier (R. rubiginosa); the Scotch rose (R. spinossissima); and the memorial rose (R. wichuraiana). The two very best of these foreign hardy roses, however, are the Japanese rose (R. rugosa) in all the Northern states, and the Cherokee rose (R. lævigata), which has become naturalized throughout the Southeastern states and is as indispensable as though it were native. This really constitutes a long and important list of hardy shrubs and is sufficient to make a splendid rose garden in itself, yet to this may be added a considerable number of garden varieties which may be also grown as shrubs. One of the most striking examples in this list would be the ever-popular Crimson Rambler and all its kin. This variety, which is seen habitually climbing over the house porch, really makes a splendid flowering bush when it is annually pruned back to the ground. This sort of pruning is very simple and always successful, and Crimson Rambler, Lady Gay, Dorothy Perkins, or any other variety of this group when managed thus makes a gorgeous addition to the flower garden. In the same way we may use all the beautiful varieties of the Japanese Rosa multiflora, also the Lord Penzance hybrid sweetbriers and many others.

As a matter of fact this group of thoroughly hardy shrubby roses gives the greatest opportunity for successful rose gardening to be found in the gardens of the Central and Northwestern states. These kinds are thoroughly able to meet the conditions of soil and climate, are perfectly willing to give abounding harvests of beautiful flowers in due season and are, in fact, fully as beautiful in their own way as the choicest and tenderest tea roses.

Municipal rose gardens

In Hartford, Connecticut, there is a magnificent public rose garden. It is probably the finest rose garden in America, and almost certainly the best one outside the Pacific Coast states, where roses really grow. Here the most expert care is available, and here the expense, which would be too much for the private family, is negligible when distributed to all the tax payers of the big city. And so the rose garden in Elizabeth Park is one of the glories of Hartford, and the citizens go out by thousands and thousands every day in June and July to enjoy their roses, and visitors come from hundreds of miles around from all neighboring cities and states to see this splendid display.

Chicago has a very beautiful public rose garden in Humboldt Park; Minneapolis has a newer and wholly successful municipal rose garden in Lyndale Park, and there are several others of only less renown.