The rose, the architect and the gardener.

Roorbach, Eloise. "The rose, the architect and the gardener." Craftsman 26, no. 3

(June 1914): 272-278.

[https://library-projects.providence.edu/rosarium/view?docId=tei/rg0133.xml]

Both architects and gardeners appreciate, perhaps more clearly today than ever before, the close kinship that exists between their respective arts and the harmony that may link the solid surfaces of brick and stone to the delicate growths of Nature. Each is a complement to the other. The walls and porches of the house, the pergolas and summer-houses, form supports for vines and backgrounds for shrubs and flowers of the garden, while they, in turn, serve as architectural adjuncts, softening the lines and edges, brightening the flat surfaces, in short, completing, by their tender gracious presence, the whole exterior of the home.

Foremost among the plants whose foliage and blossoms add such beauty to the builder’s scheme, is the rose—the royal member of the garden. Whether as bush, standard or climber, its richness of color and the decorative quality of its foliage and bloom seem to fit it supremely for putting the finishing touches to both house and garden. Planted at the base of a wall, or beside the garden entrance, reaching up tiptoe to a casement window, winding lovingly about the veranda pillars, trailing its man-petaled glory over a trellis or drooping luxuriantly from the curve of a garden arch—wherever and however it may be grown, the rose is sure to add to the outdoor beauty, and may transform into a veritable bower of color and fragrance even the humblest spot.

The soil is the first thing to consider when planning a rose garden, no matter in what part of our land it is to be. A blossoming rose makes a great demand upon the soil, and this must, therefore, be of the richest, else the flowers will not be able to exhale their sweetest perfume, bring to perfection the tenderness and richness of their color, or attain their fullest glory of form. Moreover the plant must be wisely nourished, protected from rough winds and destroying parasites.

Even in California, the land of true flower magic, where Nature has been most generous and kindly, a little scientific treatment will amazingly increase the wonders. The novice hopefully starts his Californian garden under the impression (gleaned from "booming" pamphlets) that his careless cuttings will put forth roots the second day after being pushed a few inches into dry, unprepared earth. He soon learns, however, that if he wishes a rose to climb up his porch and cover the new shingles with a mass of bloom, he must give it a rich, well loosened soil, and consider its needs as well as his own wishes.

If the ground where the roses are to bloom lacks natural drainage, an artificial one can be provided. Experienced gardeners declare that even in the most inauspicious situations roses have bloomed profusely when scientifically planted. One gardener whose rose hedge was the wonder of the whole countryside in blossom time, explained how he accomplished the miracle. He dug a trench a little more than two feet deep, loosened the dirt with a pickaxe, spread a layer of loose stones and gravel in the bottom, scattered ashes over the stones (to prevent clogging) then filled in with rich loam mixed with sand and vegetable matter. He also added a top dressing of well-decayed manure each spring.

In planting any rose, whether a standard or climber, the hole should be dug much larger than needed, and the surrounding dirt loosened with a pickaxe. Some growers advocate blasting with dynamite, as it not only loosens and aerates the ground but also destroys dangerous grubs and insects. The hole must be filled with finely screened loam, enriched with decaying vegetable matter. Roses do better if shipped in pots instead of being wrapped in dirt, for the young rootlets will not stand rough treatment. January, before the plant begins to send out new roots, is a good season for transplanting in California. It is better not to let the blooms die on the bush, but to keep them culled, and after blooming, the old flower stalks must be cut back. In the spring, one should cut out all dead and unnecessary wood, remembering that ramblers flower on old stalks, and the standard or bush varieties flower only on new canes. If the bush is wanted to assume a spreading form, the cane may be cut just above an outside eye.

California architects are realizing the immense importance of designing their houses from the curb of the street to the back of the lot, which means that when they undertake the construction of a home, their plans include a garden, walks and walls also, for it is an understood thing here that a garden is part of a home. So they are becoming practical landscape gardeners as well as designers of buildings. We now see garden colors handled with artistic judgment. The new red houses no longer have a cerise climber on one porch and a yellow bankshia on the other. Neither is every flower of a catalogue gathered into one erratically blazing star or crescent. Instead of a motley riot of incongruous color, there are the choicest of color harmonies. The prevailing colors are first determined upon, then the house is toned into a fitting background.

An important point to decide is the color scheme of the garden, whether it is to be yellow, pink or lavender or blue. (A lavender garden with a small white house in its center is as nearly ideal as heart of woman can wish.) The climbing rose is really the keynote of the whole; all colors are chosen but to offset its varied beauty.

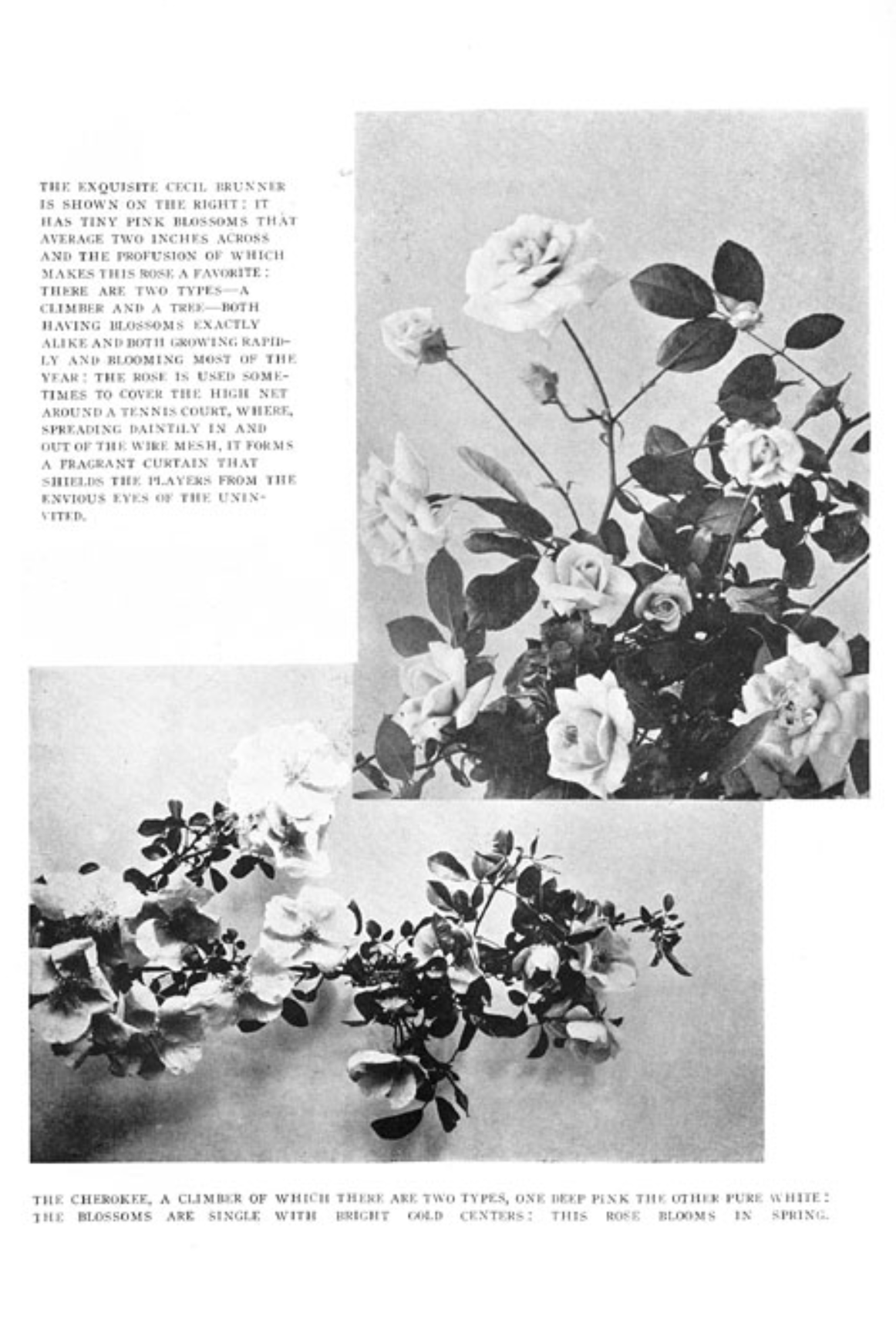

The climbers that rule the color of Californian houses are many. The Cherokee, though introduced but a few years ago, has become a universal favorite. Its beauty, too irresistible to be denied, prevents it from becoming commonplace. It is seen shading pergolas and covering sheds; it separates lawns from streets in the form of a hedge, or is festooned from tree to tree around the four sides of country estates, dripping with pink or white, yellow-centered blooms which look like wild roses glorified. The petals are graceful in the extreme, crinkling like poppies at the edges, and the foliage is glossy and lovely. The Cherokee’s normal size, if given half a chance, is five inches in diameter. It is quite hardy and an early bloomer.

The Cecile Brunner’s profusion of small pink blossoms make it another favorite. It is sometimes used to cover the high net around a tennis court. It spreads daintily in and out of the wire mesh until it forms a fragrant curtain, delicately shielding the players from the envious eyes of the uninvited.

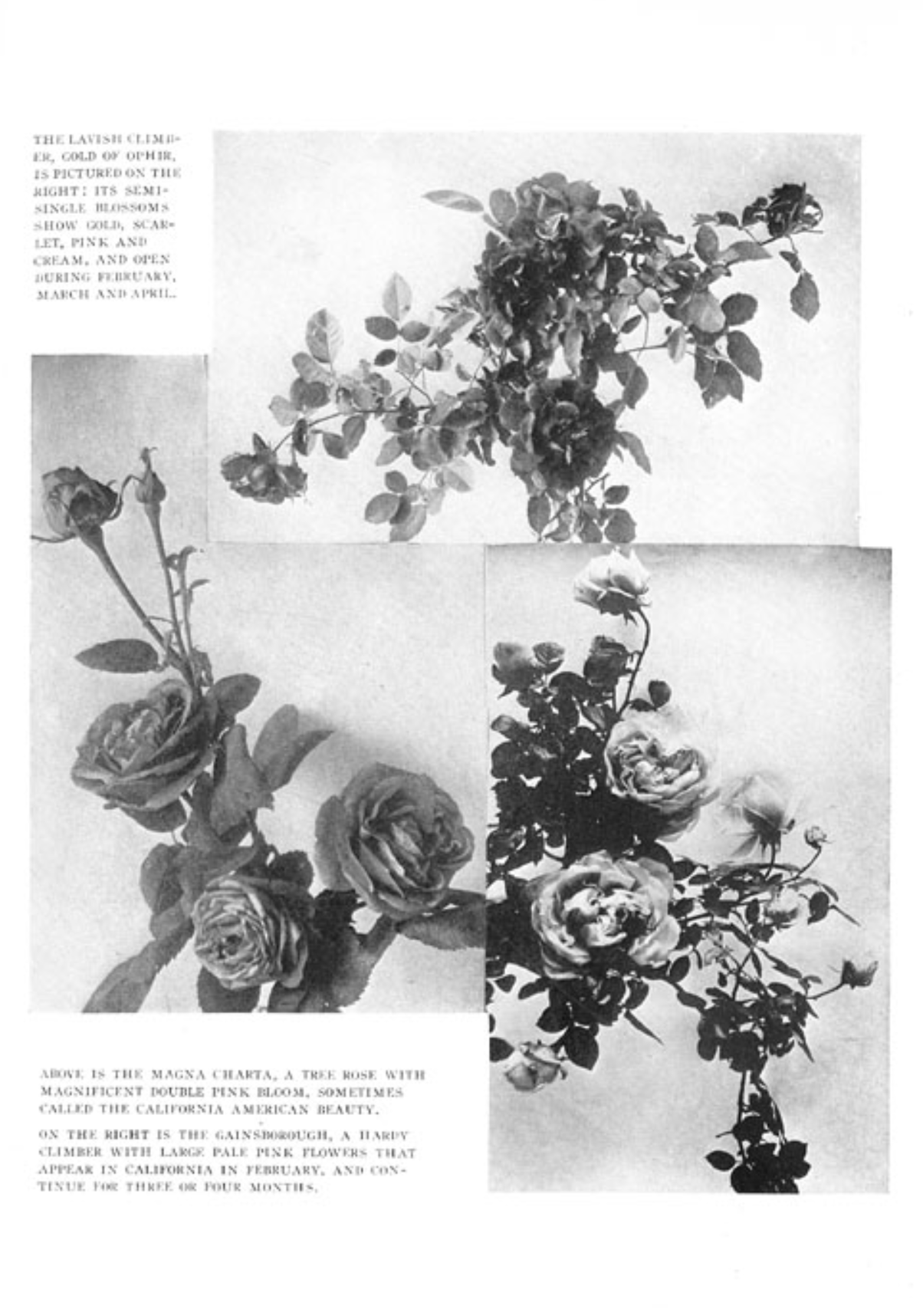

The Gold of Ophir’s luxuriant habits make it the flower embodiment of California’s legends of wealth. Its rich gold and orange petals melting into varied hues of rose and deep cream toward the heart, seem to have drawn their richness from some hidden stratum of ore.

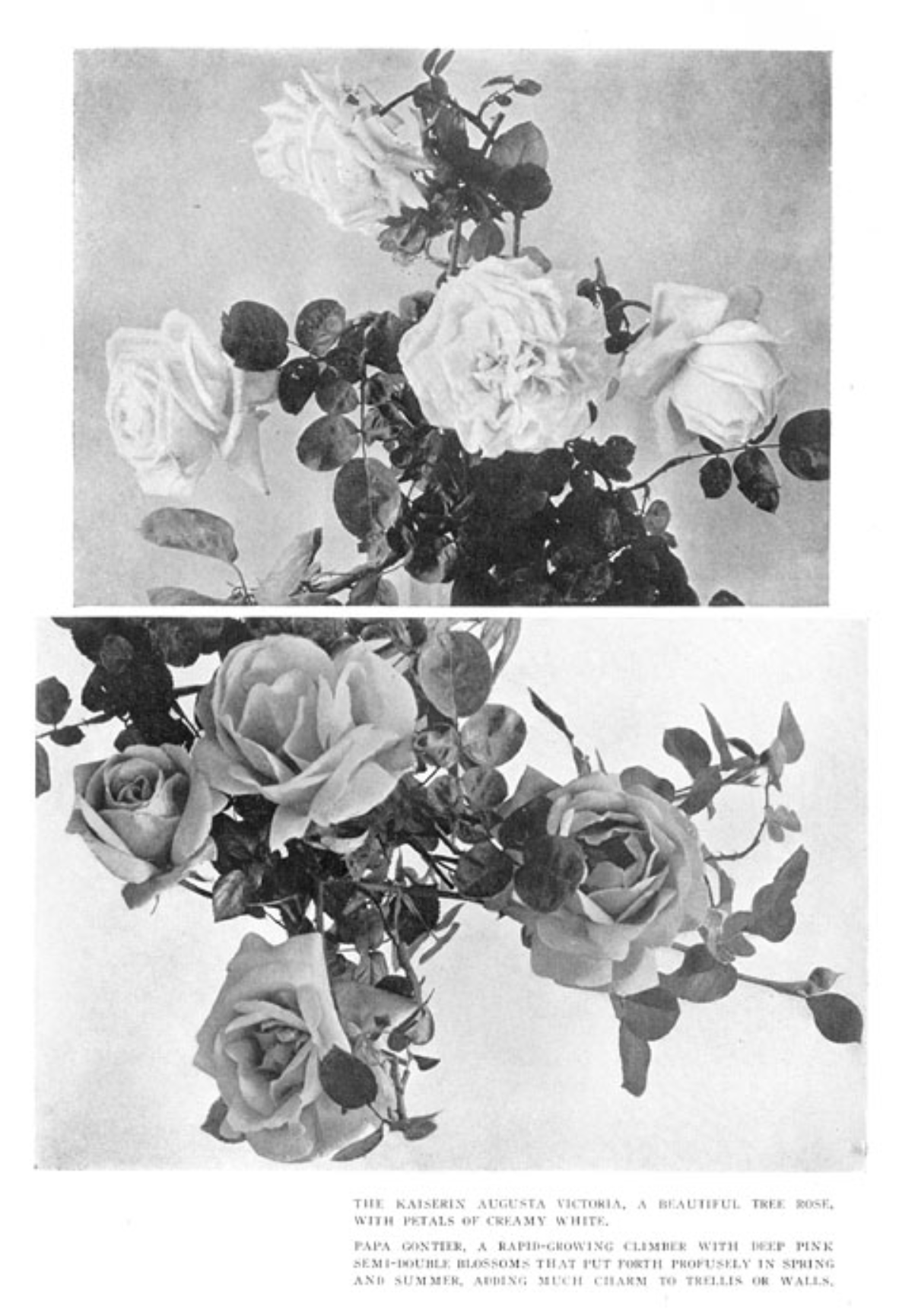

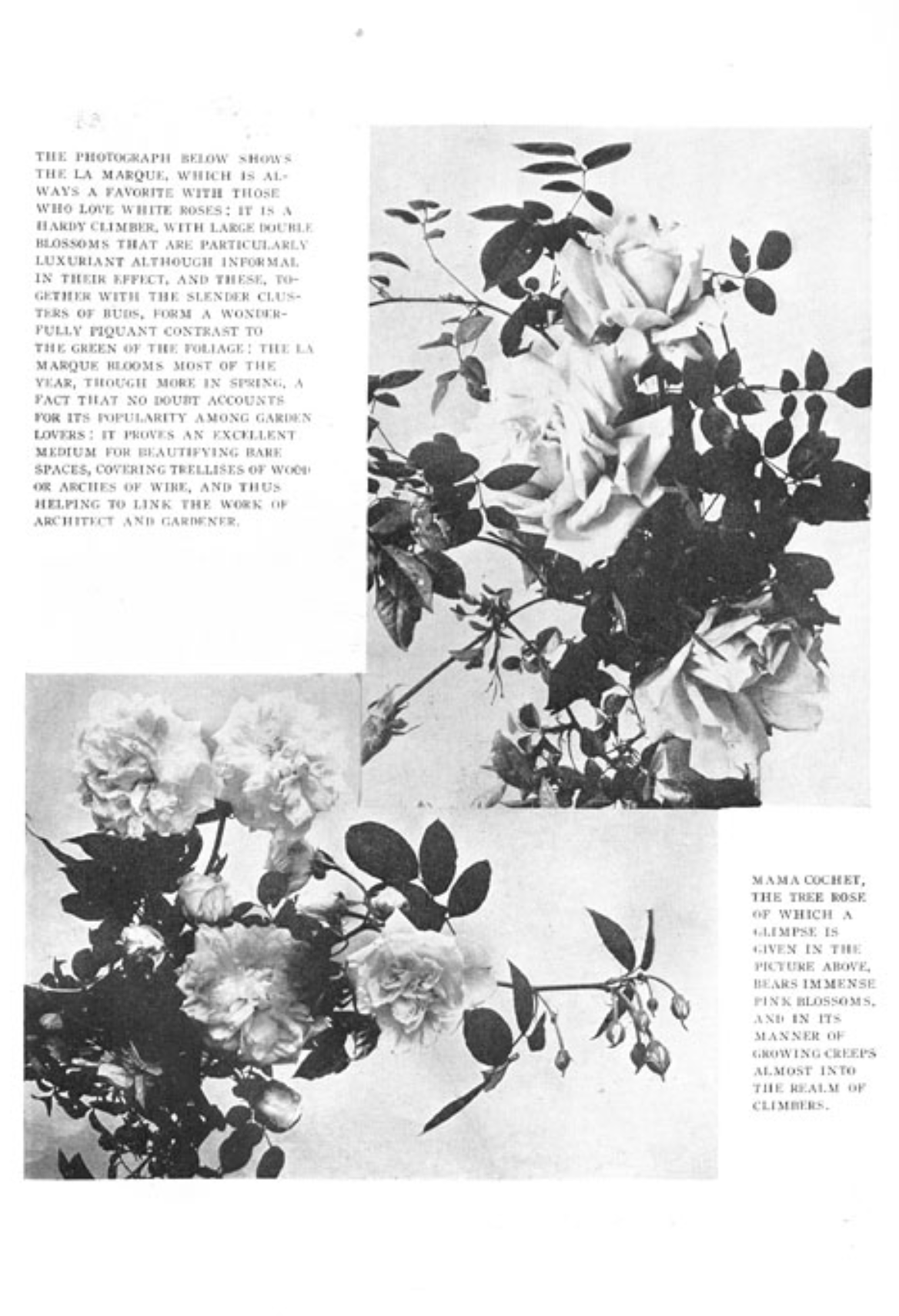

The Gainsborough is a hardy climber, unfolding large, pale pink flowers that nod heavily through pergola arches. The La Marque is a favorite for those who love white roses, and the climbing hermosa’s delicate rose-pink blossoms endear it to many. The crimson rambler is a favorite too well known to be described; so also are the rosy red prairie queen and deep pink Papa Gontier. Many of the climbers are trained to form exquisite living fences between neighboring yards, and are made low so that neighbors may gossip over garden doings, exchange slips and admire one another’s possessions.

Among the tree roses which creep well into the realm of climbers may be recommended the lovely white bride, the crimson baby rambler, the deep pink Alice Roosevelt, the yellow Safrono, the pink Mama Cochet, the creamy white Kaiserin Augusta Victoria and the magnificent double pink Magna Charta.

Californians sometimes start a border of dwarf edging-roses such as the two white favorites Schneikopf and Annie Marie Montravel, and the two pink ones, the Mignonette and the Clothilde Soupert. Back of these are set many bush and standard varieties, while still farther back are climbers mounting upon walls and trellises. Such a rose border, if let alone, will mass and tangle together in irresistible fashion; in fact the more a climbing rose is permitted its own way, the more graceful and charming it becomes.