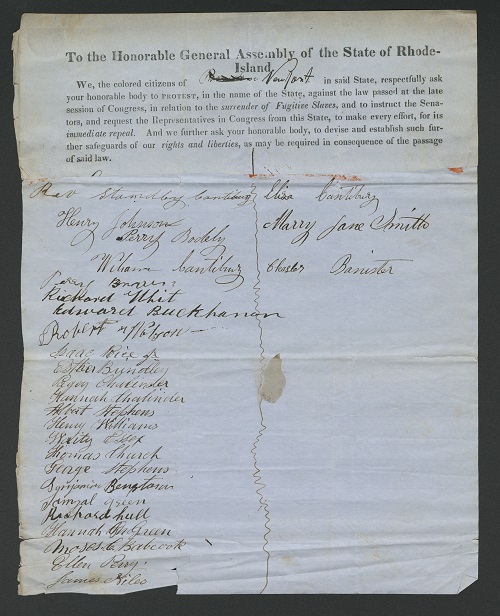

Petition for Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law from the “colored citizens” of Newport

This is a petition was signed by the “colored citizens” of Newport in February of 1851 in response to the Fugitive Slave Act that passed Congress in September of 1850. The Act required northerners in “free states” to aid in the capture and re-enslavement of those who had fled southern “slave states.” Petitions such as this one were signed by citizens all over the state of Rhode Island.

Scanned copies of the petitions can be found on the Rhode Island Secretary of State’s website.

We “pledge to sacrifice our lives and our all”: Rhode Islanders’ Involvement in the Underground Railroad

Essay by Elizabeth C. Stevens. Editor, Newport History

The Underground Railroad in Rhode Island as “myth and legend” 1Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (New York: Harper Collins, 2005), 4

In writing the narrative of the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island, one must try to piece together the scraps of information and clues that might give us just a glimpse of the effort to aid self-emancipated men, women and children seeking to escape slavery.

Rhode Islanders Enslaved and Free

In the history of Rhode Island, from the time there was slavery, the enslaved sought freedom. One need only look at the “Runaway slave” advertisements in the Newport Mercury newspaper in the eighteenth century to see that people were “self-emancipating” from their enslavers. 2Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York: New York University Press, 2016), 54-55 Those who decided to take the risky and dangerous step of self-emancipation were often aided by sympathetic friends, family, and strangers in their quest to claim freedom. One well-known Rhode Islander who assisted freedom seekers beginning in the late eighteenth century was Moses Brown, the Quaker abolitionist in Providence, who had once owned slaves. Brown’s farm, centered at the intersection of what is now Wayland and Humboldt Avenues on Providence’s East Side, was a waystation for enslaved people seeking freedom. For example, in 1792, Quaker contacts in New Bedford arranged for a man named John, his wife, and some of his family to go to Brown’s home in Providence when John’s “reputed owner” threatened to come to New Bedford to take the family back into slavery. 3Kathryn Grover, The Fugitive’s Gibraltar: Escaping Slaves and Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachusetts (Amherst, University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), 68-69. See also, Augustine Jones, “Moses Brown: His Life and Service”: A Sketch Read Before the Rhode Island Historical Society, October 18, 1892, 20, and Mary Ellen Snodgrass, The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places and Operations 2 vols. (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 2008), 1: 83 It is known that the Quaker family of Arnold Buffum in North Smithfield gave refuge to a family of freedom seekers from New York State in the 1780s, and, with the aid of a “smart young colored laborer,” defended them from re-capture by their former enslaver. 4Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences (Central Falls, R.I.: E.L. Freeman, 1891), 8-9 We can be certain that a number of unknown persons, many of them African-Americans, assisted people in their quests to self-emancipate from enslavement.

“Services for weary travelers”: The Fayerweather Family of Kingston, R.I.

After gradual emancipation went into effect in Rhode Island into the mid-nineteenth century, freedom seekers were more likely to travel on the Underground Railroad from places in the South where slavery was still legal. Sarah and George Fayerweather of Kingston, Rhode Island, are said to have aided freedom seekers in the mid-nineteenth century, although historians note that there is no material or written evidence of their Underground Railroad involvement. 5Christian McBurney, “Prudence Crandall, Sarah Harris Fayerweather and Ann Hammond: Their Pre-Civil War Struggle for Equality for Black People,” Accessed March 21, 2021 [link] African-American Sarah Harris (1812-1878) was born in Connecticut and studied at Prudence Crandall’s famed school for Young Ladies of Color in the early 1830s.6Kabria Baumgartner, In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America (New York; New York University Press, 2019), 13-45 In 1833, Sarah married George Fayerweather, a blacksmith, whose family went back several generations in southern Rhode Island and who was a descendant of both French West Indians and Indigenous Narragansetts. After their marriage, the Fayerweathers moved to New London, Connecticut, and then in 1855 to Kingston, R.I., where George Fayerweather’s extended family lived. Numerous sources maintain that the Fayerweathers aided freedom seekers at their home in Kingston.7Snodgrass, Underground Railroad, 1:187; George Fayerweather Homestead, South Kingstown, accessed April 14, 2021 [link]; Hallie Quinn, ed., Homespun Heroines (Xenia, Ohio: The Aldrine Publishing Co., 1929), 25-27; Biographical note, Guide to the Fayerweather Family Papers. 1836-1862. University of Rhode Island Special Collections, accessed March 3, 2021 [link]

Despite the lack of hard evidence, it seems likely that the Fayerweathers did assist self-emancipated persons. Sarah Harris Fayerweather was an antislavery advocate and a friend of William Lloyd Garrison and his family. She distributed copies of Garrison’s incendiary newspaper, The Liberator in the Kingston area and gave support to abolitionist causes. She apparently sent Helen Garrison, William Lloyd Garrison’s wife, a special cake every year on her birthday. Aside from her abolitionist work, Sarah Harris Fayerweather also ran the household for her family. She was the mother of six children, born between 1834 and 1846.

In discussing Sarah Harris Fayerweather’s contribution to the Underground Railroad, historian Maritcha Lyons highlighted the roles that women played in households that were part of the Underground Railroad. Women’s work in caring for freedom seekers “involved the procuring of garments for change and disguise, the collection of extra food, the selection of places for hiding and security, last but not least the proffer of first aid services to weary travelers long deprived of the barest opportunities for cleanliness either of person or clothing.” It seems likely, given her adherence to the antislavery cause, that Sarah Fayerweather, and her husband George gave refuge and assistance to self-emancipated people.8Maritcha Lyons, “Sarah Harris Fayerweather,” in Quinn, ed., Homespun Heroines, 25-27. Maritcha Remond Lyons was a teacher and Black activist in Brooklyn, N.Y. She was the first African-American graduate of Providence High School girl’s department in 1869. (Adam Rozin-Wheeler, “Maritcha Lyons (1848-1929),” accessed April 5, 2021 [link])

“Under their hospitable roof”: The Rice and Downing families of Newport, R.I.

Another Rhode Island family that made their home a stop on the Underground Railroad was Isaac and Sarah Ann Casey Rice, who lived at 23 Thomas Street in Newport. Isaac Rice (1792-1866) was a prominent leader in the African-American community in Newport who helped to found and support the African Union Society and the African Benevolent Society. He worked as a skilled gardener for the Gibbs family and, later, as a successful caterer in the city. Sarah Ann Casey Rice was the granddaughter of Abraham Casey, a founding member of the Free African Union Society in Newport in 1780. Isaac Rice was a good friend of the famed antislavery agitator Frederick Douglass. Douglass and other antislavery activists, such as Charles Lenox Remond and Henry Highland Garnet, stayed at the Rices’ house while in Newport, giving antislavery lectures in the 1840s and 1850s.9Richard C. Youngken, African-Americans in Newport: An Introduction to the Heritage of African Americans in Newport (R.I.: R.I. Historical Preservation Heritage Commission and R.I. Black Heritage Society, The Newport Historical Society, 1998), 24; Charles A. Battle, Negroes on the Island of Rhode Island (Newport: Newport Black Museum, 1932), 30; Akeia A. F. Benard, “The Free African American Cultural Landscape, Newport, R.I., 1774-1826” Appendix 1, accessed March 30, 2021 [link]; Joey La Neve De Francesco, “Abolition and Anti-Abolition in Newport, 1835-1866,” Newport History 92 (Winter/Spring 2020): 13; Snodgrass, Underground Railroad, 2: 446; Isaac Rice homestead, Thomas Street, Newport, accessed April 14, 2021 [link]; “Isaac Rice,” in Rhode Island African American Data, accessed April 14, 2020 [link]; Irving H. Bartlett, From Slave to Citizen: The Story of the Negro in Rhode Island (Urban League of R.I., 1972), 52

We don’t know the specifics of Isaac and Sarah Rice’s Underground Railroad work. Historian Charles A. Battle asserted that Isaac Rice, who was born a free man, “learned much of the horrors of the institution [of slavery] from the testimony of servants who accompanied their masters to Newport to spend the summer months.” Because Newport was a seaport, there were undoubtedly opportunities to assist freedom seekers who arrived in the town by water from other ports on the Atlantic coast. Battle wrote that “Many an escaping slave found food and shelter under [the Rices’] hospitable roof.”10Charles A. Battle, Negroes on the Island of Rhode Island (Newport: Newport Black Museum, 1932), 29-30; the author is also grateful to Kimberley Conway Dumpson, J.D., a descendant of Isaac and Sarah Rice, who is writing a book about the Isaac Rice family, for her insights Abolitionists Jethro and Anne Mitchell, white Quakers who lived in Middletown, were also apparently part of the Underground Railroad effort in the state. They communicated with Jethro’s brother, Daniel Mitchell, who lived in Pawtucket.11On the involvement of the Mitchell family, see James S. Rogers to Wilbur Siebert, April 17, 1897, accessed April 2, 2021 [link]

Since the eighteenth century, wealthy Southerners had vacationed in Newport, some bringing their enslaved servants. The majority of white Newport residents were sympathetic to Southern planters and their families who spent the summer months in the city.12Joey La Neve De Francisco, ”Abolition and Anti-Abolition in Newport,”1-37; Richard Rohrs, “’Where the great serpent of Slavery. . . basks himself all summer long’: Antebellum Newport and the South,” The New England Quarterly, vol XCIV (March 2021): 99-100 Nevertheless, it is highly likely that some Newport residents aided enslaved people in their quest for freedom. There is evidence that enslaved persons “ran away” from their enslavers in Newport, including a mother and a daughter from Kentucky who fled to Boston in the summer of 1859.13William Kauffman Scarborough, Masters of the Big House: Elite Slaveholders of the Mid-Nineteenth-Century South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003), 38 The two women may have been assisted in their journey by local Newport sympathizers such as Isaac Rice. Newport abolitionist Sophia Little apparently helped an enslaved person in Newport to escape as well, although details are scarce.14Deborah Bingham Van Broekhoven, The Devotion of These Women: Rhode Island in the Antislavery Network (Amherst, Mass.: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), 131 Yet historian Richard Rohrs asserts that “there is no evidence that Newport residents routinely helped slaves to escape or resisted the recapture and return of fugitive slaves.”15Richard Rohrs, “’Where the great serpent of Slavery. . . ,” 99-100 Due to the discretion, secrecy and danger involved in the Underground Railroad work however, there is simply no way to ascertain the actions of Newport residents in aiding freedom seekers to escape. Paul Cameron, an enslaver of hundreds of people in several Southern states, visited Newport and other northern resorts in the summer of 1857.16William Kauffman Scarborough, Masters of the Big House, 34 Writing from Nahant, Massachusetts, to his father-in-law, after visiting Newport, Cameron remarked, “What think you of seeing 90 negro men in one Hotel as servants nearly everyone a runaway from the South?”17J.G. deRoulhac Hamilton, ed., The Papers of Thomas Ruffin (Raleigh, N.C.: Edward and Broughton State Printers, 1918), 2:567-68, Publications of the North Carolina Historical Commission, accessed April 17, 2021 [link]

Cameron may have referred to the Sea-Girt Hotel, founded by George T. Downing in Newport in the mid-1850s. Perhaps the most successful entrepreneur in Newport at the time, Downing lived in New York City, where he and his father, Thomas Downing, both leading civil rights activists, were deeply involved in Underground Railroad activities. George T. Downing owned one of the most popular restaurants in New York City and came to Newport in 1846 to open a similar establishment. Over the next few years, Downing built the Sea-Girt House, a hotel on South Touro Street that was completed in 1855. The hotel promised every luxury and convenience to its elite customers, including “Dinners and game suppers, provided in private parlors, confectionary, and French and other made dishes, sent to families.,” even sumptuous “Picknics.” When his hotel burned down, under suspicious circumstances in 1860, Downing built the “Downing Block” of high-end stores on Bellevue Avenue. George Downing was a national civil rights leader who fought for the racial integration of Rhode Island public schools and for legislation and action that would ensure the rights of African Americans in the state.181856 Newport City Directory, 22; S.A.M.[Serena Ann Miller] Washington, George Thomas Downing: A Sketch of His Life and Times (Newport, R.I.: The Milne Printery, 1910); 1696 Heritage Group, “George T. Downing,” in “Gilded Age Newport in Color,” accessed April 20, 2021 [link]; May Wijaya, “The World Was His Oyster; George T. Downing,” accessed March 20, 2021 [link]; Myra B. Young Armistead, Lord, Please Don’t Take Me in August: African Americans in Newport and Saratoga Springs, 1870-1930 (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1999),23, 32-33; Snodgrass, Underground Railroad, 1:168 Richard Rohrs writes that, in 1850, 110 of the Newport’s 203 African American adult males worked as waiters in local hotels, and that, in 1850, the “Ocean House employed eighty-one waiters, fifty of whom were African Americans.”19Rohrs,“Where the great serpent of slavery…,” 90 It is entirely possible that Downing made a point of hiring self-emancipated men and women to work at the Sea-Girt, his luxury five-story hotel that included a confectionary shop and quarters for his family. Perhaps some of them were “hiding in plain sight” at his establishments. One history website asserts that Downing “was very active in the Underground Railroad, and even secretly used his hotel and restaurant as a rest station for runaway slaves on the move.”20“Meet the Founder of One of the First 5-Story, Black-Owned Luxury Hotels,” accessed April 10, 2021 [link] Given George T. Downing’s outspoken opposition to racial oppression and his father’s and his leadership in the Underground Railroad in New York, it is almost inconceivable that he would not have been active in aiding the self-emancipated while managing his successful hotel and businesses in Newport.

“Liberty or Death” African-American Rhode Islanders confront the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

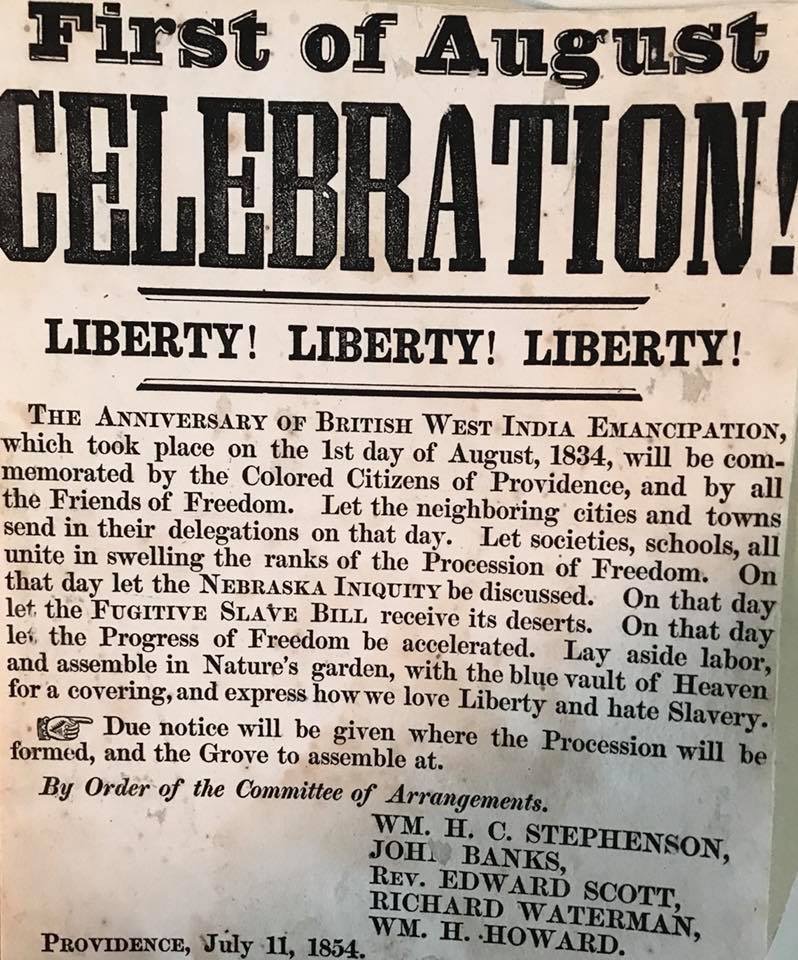

African-American residents of Rhode Island were fervently committed to aiding self-emancipated people. This is nowhere more evident than in the days following the passage of the National Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required northerners to aid in the re-enslavement of self-emancipated people. Five days after the Act passed Congress in September 1850, the Rhode Island African-American community held a “public mass meeting” at Hoppin’s Hall in downtown Providence. Many people in the assemblage had a direct connection to enslavement. Some of the attendees were free Blacks who were married to, or friends of, co-workers and neighbors of self-emancipated persons. Others had themselves fled to the state, perhaps years before, and were settled with businesses, jobs, and families. The parents and grandparents of some may have been enslaved in Rhode Island or elsewhere before gradual emancipation brought about the end of legalized slavery in the state in 1843. The “colored citizens” of Rhode Island who gathered in September 1850 vowed to “pledge to sacrifice our lives and our all” to protect their families and fellow sufferers from the consequences of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. They claimed “an undoubted and inherent right to unrestrained liberty, and the pursuit of happiness anywhere” in the country and looked to “the great moral arm of Rhode Island as a refuge from the storm, which now threatens our social habitations, with lamentations beyond endurance.” The men and women resolved that they “believe it to be our duty to God, ourselves, our children, and three millions of our brethren that are in bonds at any hour of day or night, that a slaveholder, or his agent, shall come within the limits of the State of Rhode Island for the purpose of retaking runaway slaves that we will use every means that nature or art may place into our hands to deprive him of his object.” Their final resolution was “that we who have escaped from chains, fetters and the slave driver’s lash, are determined never to go back again, but have adopted the inestimable motto—Liberty or Death.”21“Meeting of Colored Citizens,” Providence Journal, Oct. 3, 1850

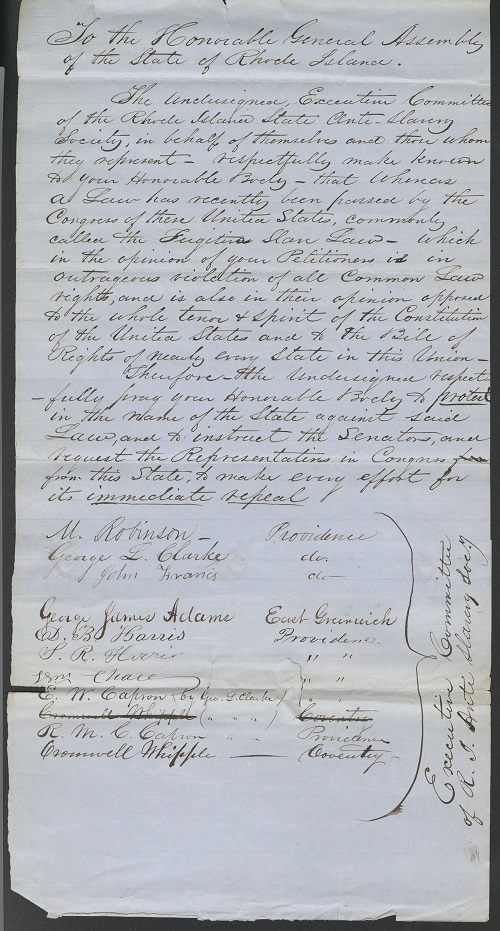

Three months later, members of the African-American communities of Providence and Newport delivered petitions to the Rhode Island General Assembly calling on their legislators to “PROTEST in the name of the State,” against the new Fugitive Slave law, and to demand that R.I. representatives and senators in Washington “make every effort,” for the “immediate repeal” of the law. The petitions further demanded that the state legislature “devise and establish such further safeguards of our rights and liberties, as may be required in consequence of the passage of said law.22“Petition for the Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law,” from the “colored citizens” of Newport and Providence, February 1851, Newport, Providence, R.I. State Archives Signers of the petition in Providence included Edward Scott, pastor of the Second Free Will Baptist Church (also known as the Pond Street Church), a “political activist and agitator,” who himself had escaped from slavery in Virginia.23Taylor M. Polites, “1812 – 1864: Reverend Edward Scott,” Rhode Tour, accessed April 14, 2021 [link] Others from Providence who signed the petition, such as Thomas Wheeler, John Walker, and Samuel Tweedy, were recorded in the 1850 Federal Census as having been born in Rhode Island, and were married with young families. Women from Providence who signed the petition included Anna Jackson, who was forty years old and had been born in Washington, D.C., and Martha Armstead, who was thirty and had been born in Virginia. Aurelia and Peter Browning, both born in Rhode Island, signed, along with their eighteen-year-old daughter, Martha, the oldest of five siblings.24“Petition for the Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law,” from the “colored citizens” of Providence, February 1851, Providence, R.I. State Archives. Information on individual signers taken from the 1850 Federal Census for Providence, R. I. The Providence Journal apparently claimed in 1850 that there were “several hundred escaped slaves living in Providence.”25Bartlett, From Slave to Citizen, 45

Petition signers in Newport included Stanley Canterberry and his wife, Eliza Canterberry. Canterberry was a charter member of the Union Congregational Church when it was founded in Newport in 1824, and another signer of the protest petition was Ellen Perry. Esther Brinley of Levin Street, who helped to organize the Shiloh Baptist Church in Newport in the 1860s, also signed the petition. Twenty-year-old Isaac Rice, jr., as well as Richard White, who had been born in 1811 in Virginia, and Edward Buchanan, a shoemaker who was born in the “Isle of France.” [Mauritius] were other signers of the Newport petition protesting the Fugitive Slave Law. Seventeen-year-old Mary Jane Smith, who had been born in Maryland, was apparently the youngest Newporter to put her name on the document. 26Petition for Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law, from the “colored citizens” of Newport, February 1851, R.I. State Archives. Information on individual signers from the 1850 Federal census for Newport, R.I. and from Battle, Negroes of Rhode Island, 23, 25 We don’t have documentation that any of the Rhode Islanders who attended the September 1850 meeting vowing to resist “by every means,” the return of themselves, their friends, neighbors and families into enslavement, and who signed the subsequent petitions to the State Assembly, had an involvement in the Underground Railroad. Yet it seems plausible that the signers would have taken any opportunity to subvert the law by assisting people seeking freedom from enslavement. We do know, for instance, that Eugene Scott’s Second Freewill Baptist Church in Providence provided aid to freedom seekers and Isaac Rice jr.’s family also assisted fugitives in Newport. African-American Newporters apparently formed a “vigilance association” similar to those in other cities “to be on the lookout, both for the panting fugitive and also for the oppressor when he shall make his approach.” Vigilance committees, led by Black abolitionists, up and down the East Coast took a militant approach to the protection of self-emancipated people who were endangered by the Fugitive Slave Act.27Quotation from Bartlett, From Slave to Citizen, 46; Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 384-85

“President of the Underground Railroad”

Members of the Second Free-Will Baptist Church (also known as the Pond St. Baptist Church), where civil rights activist Edward Scott was pastor from 1846-1864, were key actors in aiding freedom seekers. Scott, who was born around 1812 and died in 1864, was a “kind of President of the Underground Railroad” in Providence. He had been born into slavery in Virginia and was himself a freedom seeker. In a speech given in Providence in 1857, Scott recalled that when he was thirteen, he had been separated from his family, put in handcuffs, and “carried on board” a ship waiting in the Norfolk River, which took him to the slave market in New Orleans. Despite his fervent wish to see his mother “once more,” he was not allowed to see her before he was taken away. 28“Speech by Edward Scott, Delivered at the Roger Williams Freewill Baptist Church, Providence, Rhode Island, 6 October 1857,” and annotation, in C. Peter Ripley, ed., The Black Abolitionist Papers, Volume 4, The United States, 1847-1858 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 1991, 366-370; Providence Daily Journal, October 8, 1857, p. 2

Once in New Orleans, however, Scott was “stowed away on a vessel for New York City.” Details of his escape are not known. Settling in Maine, Scott became a Freewill Baptist and was ordained a pastor in 1845 when he took the reins of the Second Freewill Baptist Church in Providence. The church “grew quickly under his leadership and became a center for local antislavery activities.” Scott was regarded as “one of the city’s leading abolitionists.” Among other activities, Scott “directed efforts to aid and protect” freedom seekers in the city. He “organized the Rhode Island Committee of Vigilance, which used the church as its base of operations.”29“Speech by Edward Scott,” C. Peter Ripley, ed., The Black Abolitionist Papers, Volume 4, 366-370 In his history of the African-American community in Rhode Island, historian Irving Bartlett writes that, by 1849, Scott “felt obliged to print an open letter in the Providence papers requesting funds for his church” in their work for the Underground Railroad. Scott’s letter stated that the church had assisted over 16 freedom seekers in the past few months.30 Bartlett, From Slave to Citizen, 45 After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, Edward Scott “publicly revealed his fugitive slave status for the first time and persuaded the Freewill Baptist Anti-Slavery Society to advocate militant resistance to the Fugitive Slave Law.”31“Speech by Edward Scott,” in C. Peter Ripley, ed., The Black Abolitionist Papers, Volume 4, 368n; Pond Street Church is listed in the booklet, The Underground Railroad in New England (American Revolution Bicentennial Administration) n.d., p.6; Pond Street Baptist Church, Providence, West Side, accessed April 12, 2021 [link]

Other houses of worship in Rhode Island provided shelter and assistance to self-emancipated people during this period. The Bethel A. M. E. Church, which grew out of the African Freedmen’s Society that was founded in Providence in 1795, was located at 193 Meeting Street in Providence. In the mid-twentieth century, while working on his history of African Americans in Rhode Island, Dr. Carl Gross spoke with Mrs. Florence West Ward, whom he believed was one of the oldest living members of Bethel A.M.E. Church at the time. Mrs. Ward recalled for him that there was a “sub-cellar in the church” on Meeting Street where freedom seekers were hidden and cared for on their way to freedom. The Bethel A.M.E. church’s involvement in the Underground Railroad is commemorated in a plaque at the church, now located at Rochambeau Avenue, and a marker at its original site on Meeting Street on the Brown University campus.32Dr. Carl Russell Gross typed notes for an interview with Mrs. Florence West Ward, and map of Underground Railroad routes in New England, MSS 9001-G, B-12, Gross, Rhode Island Historical Society; p. III Interviews, Mrs. Florence West Ward, and program for 161st Anniversary of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church with a hand-written note, Providence, October 21, 1956, Gross, Carl Russell, “Manuscript B” (1971). Dr. Carl Russell Gross Collection. 2; Rhode Island College Special Collections, accessed March 25, 2021 [link]; “East Side Underground Railroad site to be commemorated Oct. 28,” accessed March 20, 2021 [link] It is said that the Quaker caretaker at Truro Synagogue in Newport, which was not in active use in the years before the Civil War, hid freedom seekers in a cellar below the synagogue. Mary Ellen Snodgrass writes that, “Oral stories credit the congregation with offering shelter, clothes, and food to escapees from the South until transporters could complete the link with the next safehouse in Newport.”33Snodgrass, Underground Railroad, 521; Charles L. Blockson, The Underground Railroad (New York: Prentice Hall, 1987). 263

“Food, raiment, and comfortable homes”

The office of the R.I. Anti-Slavery Society in the Arcade in downtown Providence provided a sort of underground railroad station in plain sight during the 1840s and early 1850s. A young antislavery worker named Amarancy Paine ran the office and was secretary of the Providence Ladies Anti-Slavery Society. Amarancy Paine (1812-1882) grew up on a farm in Smithfield, worked in a factory, and was a passionate advocate for the immediate abolition of slavery.34William F. Davis, Saint Indefatigable: A Sketch of the Life of Amarancy Paine Sarle (Boston: D. Lothrop & Co., 1883 In her report on the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society’s work in 1848, Paine wrote that “A large number of fugitives have come to us during the past year for whom food, raiment and comfortable homes have been provided; or if wishing to journey farther, means afforded them to do so. . .Let all come who have the good fortune to escape from slavery’s grasp. . .”35“Report of the Providence Ladies Anti-Slavery Society for 1848,” Providence Journal. March 1, 1849 The Ladies Anti-Slavery Society raised money to help freedom seekers by organizing fairs, teas and picnics. At one Fair, held in Mechanics Hall in Providence in September 1848, a notice in the Providence newspaper promised the sale of “choicest articles. . . ice cream, pastry . . . and the other good things eatable, or books or clothing or fancy articles,” as well as fortunes told by “the fate lady” and “pretty things from the grab bag.”36“Come Again to the Fair,“ Providence Journal, Sept. 8, 1848 In an annual report in the 1850s, Amarancy Paine asserted that, “A greater number of fugitives has come to us than during any previous year. At one time, there was a company of eight persons, five of them children; on another occasion, six persons arrived.” The Society also helped self-emancipated people find employment. Paine mentioned several who were diligently saving money, hoping to rescue still-enslaved family members.37“Fugitives continue to come to us in great numbers, and unless they prefer to leave the State, employment and homes are provided for them,” Paine wrote in one annual report. Davis, Indefatigable, 37, 40. Davis writes that the report, “A great number of fugitives has come to us . . .” was the”14th Annual Report” of the R.I. Ladies Anti-Slavery Society without giving the year. The Ladies Society was founded in May 1843, so I believe the “14th Annual Report would have been written around 1857.

“A hide-out in a heavily wooded tract”: Underground railroad sites in Rhode Island

Other locations in Rhode Island provide brief clues to the work of the Underground Railroad throughout the state. In her history of slavery and its aftermath in Little Compton, Marjory Gomez O’Toole gives some evidence that Deacon Thomas George T. Burgess’s home on West Main Road in the town was a “stop on the Underground Railroad.” Other white activists were Clother and Nathaniel Gifford of John Dyer Road in Little Compton, who were connected to the Underground Railroad through the Rotch family in nearby New Bedford, a hotbed of Underground Railroad activity. Gomez O’Toole writes, “One of Nathaniel’s ‘passengers’ seems to have been a child named Henry Manton from North Carolina. Manton settled in Little Compton, and his descendants continued to live there throughout the twentieth century.38Marjory Gomez O’Toole, If Jane Should Want to Be Sold, Stories of Enslavement, Indenture and Freedom in Little Compton (Little Compton Historical Society, 2016), 218-19, 220-21

Another site which is connected to the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island is the Pidge farm in Pawtucket. Formerly a tavern on the Providence city line, the home was located on Pawtucket Avenue between Pidge Avenue and Lafayette Street. According to some researchers, freedom seekers were brought over to the Pidge farm by Robert Adams of Fall River. They were hidden in the family barn. A grandson of Ira Pidge, a white man who owned the property in the mid-nineteenth century, remembered seeing this activity as a boy. Despite the Pidge grandson’s oral testimony, given in an interview in 1934, that he saw the “black men hidden in his father’s barn, “a Pawtucket resident named Charles Carroll asserted that, “I doubt seriously the use of the Pidge House. The Pidge house stands on what was the old Pawtucket Pike, almost too close to the road to suggest that it actually was a hiding place. . . Bringing a slave from Fall River to Pawtucket would involve travel difficulties and contact with close populated areas which should be avoided.’”39Betty Johnson and James Wheaton, “Pawtucket Played Role in Underground Railroad,” Our Times and Before, The Pawtucket Times, Oct. 10, 1998; “Old Pidge House Revealed as Fugitive Slave Hangout,” The Pawtucket Times, December 3, 1934)

Other Underground Railroad sites in Rhode Island include the Elizabeth Buffum Chace and Samuel Chace homes in Valley Falls, and the Jacob D. Babcock House in Hopkinton.40Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences (Central Falls: E. l. Freeman, 1891),26-39; Russell DeSimone, “Narrative of an Ashaway Teenager’s Role in the Underground Railroad Rediscovered,” accessed February 28, 2021 [link]; “Reminiscences of the ‘Underground Railroad,’” Providence Sunday Journal, January 13, 1918, Fifth Section Charles Perry, a dedicated white Quaker abolitionist in Westerly, Rhode Island and his wife, Temperance Foster Perry, also sheltered freedom seekers in their home at 4 Margin Street in Westerly. Mary Ann Best wrote that after the Fugitive Slave Bill passed in 1850, free Blacks and self-emancipated people in the Westerly area, aided by the Perrys, created a “hideout” in a “heavily wooded tract…lying between King Tom Farm and Shumuncanoc” (an area rich in the history of Indigenous people, in Charlestown). Best wrote, “Here the men threw up stone huts, topped with the saplings and laid on a sod roof. . . cooking in the open, far from the beat of a pursuing Southern sheriff.”41Mary Agnes Best, The Town that Saved A State/Westerly (Westerly: The Utter Company, 1943), 230-231; “Westerly, Charles Perry House, Stages of Freedom,” accessed April 4, 2021 [link]; Charles L. Blockson, The Underground Railroad, 263; Snodgrass, Underground Railroad, 2:409

“Considerable courage was required of all who were involved”: Writing the story of the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island

Despite having only scraps of information about the existence of the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island, it is possible to stitch together a narrative suggesting that the paths of self-emancipated people led to, and sometimes through, Rhode Island, from Westerly to Little Compton. In his quest for freedom, Frederick Douglass took a steamboat from New York to Newport, where two Quaker men helped him as he sought to board the stagecoach to New Bedford.42Frederick Douglass, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass Written By Himself ( Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications Inc., 2003), 143 Scores of Rhode Islanders—both African American and white, some who had been freedom seekers themselves—aided self-emancipated people in the decades leading up to the Civil War, and especially after the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 threatened thousands of Black people with re-enslavement and their enablers with imprisonment or onerous fines. While Valley Falls resident Elizabeth Buffum Chace recorded her pre-war work in the Underground Railroad for posterity in 1891, we have no other documents that clearly describe Rhode Islanders’ labor for this cause.43Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences Nevertheless, we can infer from the information that we do have that many others provided assistance, whether housing, clothing, transportation, money, food, jobs, or other forms of support to those who sought freedom from bondage. The lack of formal “evidence” about the Underground Railroad in Rhode Island should in no way detract from our understanding that clandestine activity was carried out by Rhode Islanders in a number of places in the state. John Michael Vlach, a professor at George Washington University, has cited the “lengthy and wide-spread expression of civil disobedience,” that was the Underground Railroad. “While considerable courage was required of all who were involved,” Vlach noted, “it was the runaway slaves who were most vulnerable and whose actions should be judged as the most valiant.”44“Underground Railroad in Massachusetts”, accessed March 25, 2021 [link]

Terms:

Memoir: a person’s written memories of his or her life experiences

Freedom Seekers: freedom seekers are enslaved individuals who liberated themselves from enslavement. You may see the term “fugitive,” “escapee,” or “runaway” used in older documents or texts. Recent scholarship acknowledges that “freedom seekers” or “self-emancipated” are the preferred terms to use since the other terms places the individual in a lawbreaking context, or one deserving of capture and punishment. See The Language of Slavery from the National Park Service for more information

Clandestine: secret

Mundane: ordinary

Narrative: story

Self-emancipation: to flee from enslavement and achieve freedom on one’s own initiative

Abolitionist: a person who worked to end slavery

Gradual emancipation: In Rhode Island, the Gradual Emancipation Act of 1784 was meant to slowly phase out slavery. According to this act, children born to enslaved parents would not remain enslaved and enslavers could manumit enslaved people that were healthy and between the ages of 21 and 40 without assuming financial responsibility

Indigenous: peoples who were native to the area, and whose ancestors were here before the arrival of Europeans

Discretion: being very careful about revealing information

Entrepreneur: a person to creates new things, usually businesses or organizations

Inconceivable: not to be believed

Inherent: naturally belonging to

Inestimable: great

Petitions: written documents addressed to government officials or others in authority, signed by a number of people

Raiment: clothing

Site: place

Testimony: a person’s words

Posterity: future generations

Civil disobedience: disobeying the law in the name of a higher law

Vulnerable: subject to harm

Questions:

This essay mentions that there are many myths and legends about the Underground Railroad. Why is that? How do we know what we know about the Underground Railroad? What types of evidence do we have? Why is there so little evidence left behind?

Although other white and Black Rhode Islanders participated in the Underground Railroad by aiding those seeking freedom, why do we know so much more about Elizabeth Buffum Chace, a white activist?

Some scholars have said that the Underground Railroad was one of America’s first interracial political movements (see The Underground Railroad: Myth & Reality by Fergus M. Bordewich). Why is that? From this essay, what white Rhode Islanders and what Black Rhode Islanders participated?

What were some of the ways Rhode Islanders protested the Fugitive Slave Act?

- 1Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (New York: Harper Collins, 2005), 4

- 2Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York: New York University Press, 2016), 54-55

- 3Kathryn Grover, The Fugitive’s Gibraltar: Escaping Slaves and Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachusetts (Amherst, University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), 68-69. See also, Augustine Jones, “Moses Brown: His Life and Service”: A Sketch Read Before the Rhode Island Historical Society, October 18, 1892, 20, and Mary Ellen Snodgrass, The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places and Operations 2 vols. (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 2008), 1: 83

- 4Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences (Central Falls, R.I.: E.L. Freeman, 1891), 8-9

- 5Christian McBurney, “Prudence Crandall, Sarah Harris Fayerweather and Ann Hammond: Their Pre-Civil War Struggle for Equality for Black People,” Accessed March 21, 2021 [link]

- 6Kabria Baumgartner, In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America (New York; New York University Press, 2019), 13-45

- 7Snodgrass, Underground Railroad, 1:187; George Fayerweather Homestead, South Kingstown, accessed April 14, 2021 [link]; Hallie Quinn, ed., Homespun Heroines (Xenia, Ohio: The Aldrine Publishing Co., 1929), 25-27; Biographical note, Guide to the Fayerweather Family Papers. 1836-1862. University of Rhode Island Special Collections, accessed March 3, 2021 [link]

- 8Maritcha Lyons, “Sarah Harris Fayerweather,” in Quinn, ed., Homespun Heroines, 25-27. Maritcha Remond Lyons was a teacher and Black activist in Brooklyn, N.Y. She was the first African-American graduate of Providence High School girl’s department in 1869. (Adam Rozin-Wheeler, “Maritcha Lyons (1848-1929),” accessed April 5, 2021 [link])

- 9Richard C. Youngken, African-Americans in Newport: An Introduction to the Heritage of African Americans in Newport (R.I.: R.I. Historical Preservation Heritage Commission and R.I. Black Heritage Society, The Newport Historical Society, 1998), 24; Charles A. Battle, Negroes on the Island of Rhode Island (Newport: Newport Black Museum, 1932), 30; Akeia A. F. Benard, “The Free African American Cultural Landscape, Newport, R.I., 1774-1826” Appendix 1, accessed March 30, 2021 [link]; Joey La Neve De Francesco, “Abolition and Anti-Abolition in Newport, 1835-1866,” Newport History 92 (Winter/Spring 2020): 13; Snodgrass, Underground Railroad, 2: 446; Isaac Rice homestead, Thomas Street, Newport, accessed April 14, 2021 [link]; “Isaac Rice,” in Rhode Island African American Data, accessed April 14, 2020 [link]; Irving H. Bartlett, From Slave to Citizen: The Story of the Negro in Rhode Island (Urban League of R.I., 1972), 52

- 10Charles A. Battle, Negroes on the Island of Rhode Island (Newport: Newport Black Museum, 1932), 29-30; the author is also grateful to Kimberley Conway Dumpson, J.D., a descendant of Isaac and Sarah Rice, who is writing a book about the Isaac Rice family, for her insights

- 11On the involvement of the Mitchell family, see James S. Rogers to Wilbur Siebert, April 17, 1897, accessed April 2, 2021 [link]

- 12Joey La Neve De Francisco, ”Abolition and Anti-Abolition in Newport,”1-37; Richard Rohrs, “’Where the great serpent of Slavery. . . basks himself all summer long’: Antebellum Newport and the South,” The New England Quarterly, vol XCIV (March 2021): 99-100

- 13William Kauffman Scarborough, Masters of the Big House: Elite Slaveholders of the Mid-Nineteenth-Century South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003), 38

- 14Deborah Bingham Van Broekhoven, The Devotion of These Women: Rhode Island in the Antislavery Network (Amherst, Mass.: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), 131

- 15Richard Rohrs, “’Where the great serpent of Slavery. . . ,” 99-100

- 16William Kauffman Scarborough, Masters of the Big House, 34

- 17J.G. deRoulhac Hamilton, ed., The Papers of Thomas Ruffin (Raleigh, N.C.: Edward and Broughton State Printers, 1918), 2:567-68, Publications of the North Carolina Historical Commission, accessed April 17, 2021 [link]

- 181856 Newport City Directory, 22; S.A.M.[Serena Ann Miller] Washington, George Thomas Downing: A Sketch of His Life and Times (Newport, R.I.: The Milne Printery, 1910); 1696 Heritage Group, “George T. Downing,” in “Gilded Age Newport in Color,” accessed April 20, 2021 [link]; May Wijaya, “The World Was His Oyster; George T. Downing,” accessed March 20, 2021 [link]; Myra B. Young Armistead, Lord, Please Don’t Take Me in August: African Americans in Newport and Saratoga Springs, 1870-1930 (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1999),23, 32-33; Snodgrass, Underground Railroad, 1:168

- 19Rohrs,“Where the great serpent of slavery…,” 90

- 20“Meet the Founder of One of the First 5-Story, Black-Owned Luxury Hotels,” accessed April 10, 2021 [link]

- 21“Meeting of Colored Citizens,” Providence Journal, Oct. 3, 1850

- 22“Petition for the Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law,” from the “colored citizens” of Newport and Providence, February 1851, Newport, Providence, R.I. State Archives

- 23Taylor M. Polites, “1812 – 1864: Reverend Edward Scott,” Rhode Tour, accessed April 14, 2021 [link]

- 24“Petition for the Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law,” from the “colored citizens” of Providence, February 1851, Providence, R.I. State Archives. Information on individual signers taken from the 1850 Federal Census for Providence, R. I.

- 25Bartlett, From Slave to Citizen, 45

- 26Petition for Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law, from the “colored citizens” of Newport, February 1851, R.I. State Archives. Information on individual signers from the 1850 Federal census for Newport, R.I. and from Battle, Negroes of Rhode Island, 23, 25

- 27Quotation from Bartlett, From Slave to Citizen, 46; Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 384-85

- 28“Speech by Edward Scott, Delivered at the Roger Williams Freewill Baptist Church, Providence, Rhode Island, 6 October 1857,” and annotation, in C. Peter Ripley, ed., The Black Abolitionist Papers, Volume 4, The United States, 1847-1858 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 1991, 366-370; Providence Daily Journal, October 8, 1857, p. 2

- 29“Speech by Edward Scott,” C. Peter Ripley, ed., The Black Abolitionist Papers, Volume 4, 366-370

- 30Bartlett, From Slave to Citizen, 45

- 31“Speech by Edward Scott,” in C. Peter Ripley, ed., The Black Abolitionist Papers, Volume 4, 368n; Pond Street Church is listed in the booklet, The Underground Railroad in New England (American Revolution Bicentennial Administration) n.d., p.6; Pond Street Baptist Church, Providence, West Side, accessed April 12, 2021 [link]

- 32Dr. Carl Russell Gross typed notes for an interview with Mrs. Florence West Ward, and map of Underground Railroad routes in New England, MSS 9001-G, B-12, Gross, Rhode Island Historical Society; p. III Interviews, Mrs. Florence West Ward, and program for 161st Anniversary of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church with a hand-written note, Providence, October 21, 1956, Gross, Carl Russell, “Manuscript B” (1971). Dr. Carl Russell Gross Collection. 2; Rhode Island College Special Collections, accessed March 25, 2021 [link]; “East Side Underground Railroad site to be commemorated Oct. 28,” accessed March 20, 2021 [link]

- 33Snodgrass, Underground Railroad, 521; Charles L. Blockson, The Underground Railroad (New York: Prentice Hall, 1987). 263

- 34William F. Davis, Saint Indefatigable: A Sketch of the Life of Amarancy Paine Sarle (Boston: D. Lothrop & Co., 1883

- 35“Report of the Providence Ladies Anti-Slavery Society for 1848,” Providence Journal. March 1, 1849

- 36“Come Again to the Fair,“ Providence Journal, Sept. 8, 1848

- 37“Fugitives continue to come to us in great numbers, and unless they prefer to leave the State, employment and homes are provided for them,” Paine wrote in one annual report. Davis, Indefatigable, 37, 40. Davis writes that the report, “A great number of fugitives has come to us . . .” was the”14th Annual Report” of the R.I. Ladies Anti-Slavery Society without giving the year. The Ladies Society was founded in May 1843, so I believe the “14th Annual Report would have been written around 1857.

- 38Marjory Gomez O’Toole, If Jane Should Want to Be Sold, Stories of Enslavement, Indenture and Freedom in Little Compton (Little Compton Historical Society, 2016), 218-19, 220-21

- 39Betty Johnson and James Wheaton, “Pawtucket Played Role in Underground Railroad,” Our Times and Before, The Pawtucket Times, Oct. 10, 1998; “Old Pidge House Revealed as Fugitive Slave Hangout,” The Pawtucket Times, December 3, 1934)

- 40Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences (Central Falls: E. l. Freeman, 1891),26-39; Russell DeSimone, “Narrative of an Ashaway Teenager’s Role in the Underground Railroad Rediscovered,” accessed February 28, 2021 [link]; “Reminiscences of the ‘Underground Railroad,’” Providence Sunday Journal, January 13, 1918, Fifth Section

- 41Mary Agnes Best, The Town that Saved A State/Westerly (Westerly: The Utter Company, 1943), 230-231; “Westerly, Charles Perry House, Stages of Freedom,” accessed April 4, 2021 [link]; Charles L. Blockson, The Underground Railroad, 263; Snodgrass, Underground Railroad, 2:409

- 42Frederick Douglass, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass Written By Himself ( Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications Inc., 2003), 143

- 43Chace, Anti-Slavery Reminiscences

- 44“Underground Railroad in Massachusetts”, accessed March 25, 2021 [link]