Rhode Island, Slavery, and the Slave Trade

Essay by Joanne Pope Melish, Associate Professor Emerita History Department, University of Kentucky

Most Americans think of slavery as solely a southern institution. In fact, the American slave trade was centered in New England, and enslaved people labored throughout the New England colonies from the mid-1600s through the American Revolution, with slavery legally existing in Rhode Island until 1842. Near the peak of northern slavery in the 1750s, there were towns in the southern part of Rhode Island whose populations were as much as 30% Black and enslaved. A few enslaved people still labored in New England on the eve of the Civil War—long after militant northern abolitionists had declared war on southern slavery.1For these and other cited statistics on the enslaved population in Rhode Island, see Evarts B. Greene and Virginia D. Harrington, American Population before the Federal Census of 1790 (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1966), 61-69 and Ira Berlin, Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves (Cambridge, MA, and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003), Table I, 272

The Enslavement of Indigenous People

Slavery was part of New England’s history from the outset of English settlement. Colonists sought to relieve an acute labor shortage in the early decades by enslaving Indians— Pequot, Narragansett, and Wampanoag captives sold into slavery after the Pequot War in 1637 and King Philip’s War in 1676. The women and children were sold to labor in English households in Rhode Island and elsewhere in New England, while most of the adult men—deemed too dangerous to remain in the New England colonies—were shipped to the British West Indies to labor in the sugar cane fields, where the average life expectancy of an enslaved person was five to seven years. In 1638, William Peirce, a privateer sailing from Salem, Massachusetts, carried seventeen Pequot captives to the West Indies and exchanged them for “some cotton, and tobacco, and negroes,” the first enslaved Africans to arrive in New England. By 1700, as wars between Native people and English settlers became more sporadic and yielded fewer Native captives, Rhode Island colonists began to concentrate exclusively on bringing captives from Africa to meet their increasing demand for labor.2Margaret Ellen Newell, Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2015), 57, 158-59; 51; and Margaret Ellen Newell, “The Changing Nature of Indian Slavery in New England, 1670–1720,” in Reinterpreting New England Indians and the Colonial Experience, edited by Collin Calloway and Neal Salisbury (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 2003), pp. 126-136. [link]

The Atlantic Slave Trade

The first slaving voyage to bring captive Africans to Rhode Island took place in 1696, when a Boston ship, the Seaflower, brought forty-seven captives from the coast of Africa and sold fourteen of them in Newport. The first recorded slaving voyage to depart from Rhode Island took place in 1700 when three sailing vessels from Newport went to Africa and brought captives from there to Barbados.

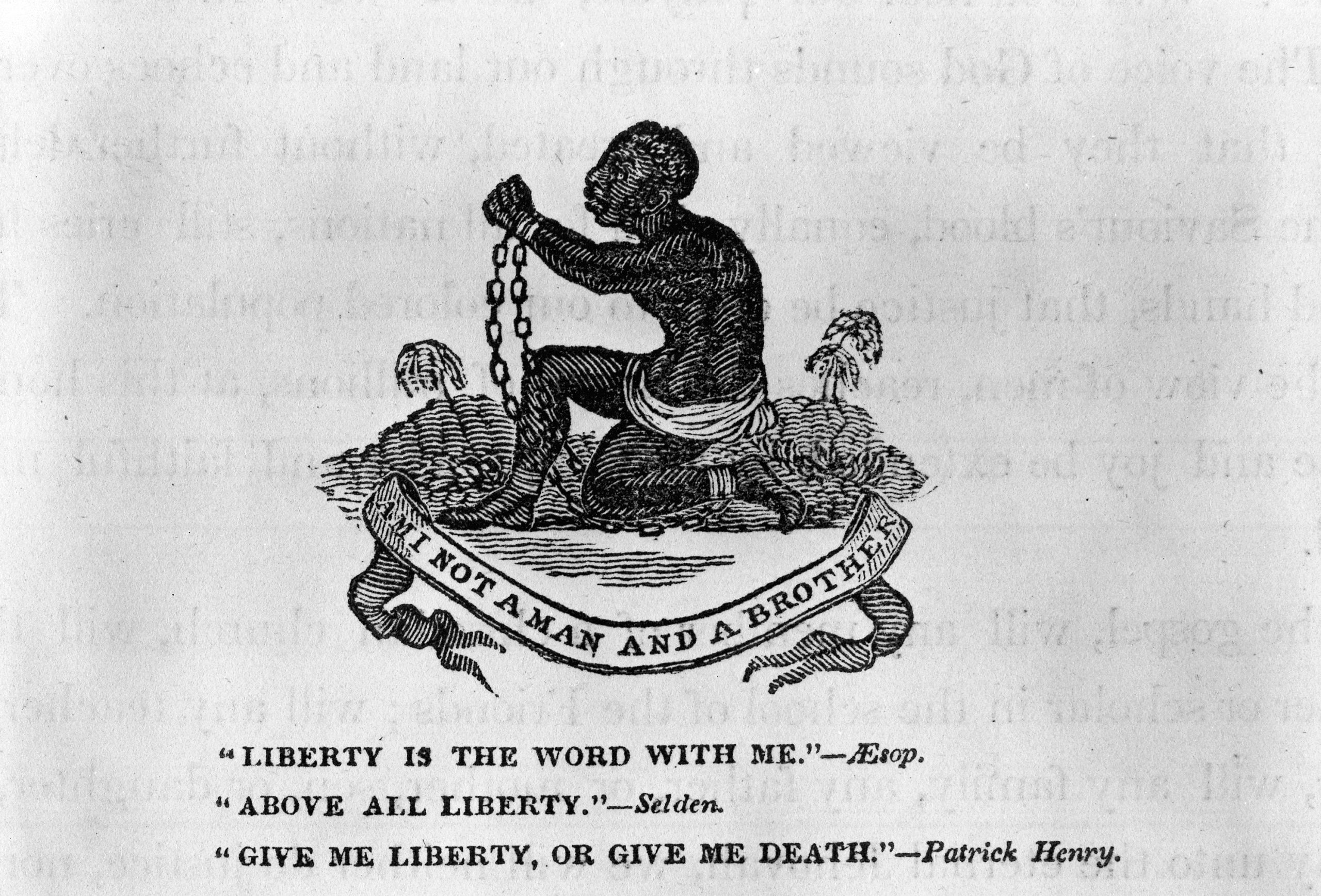

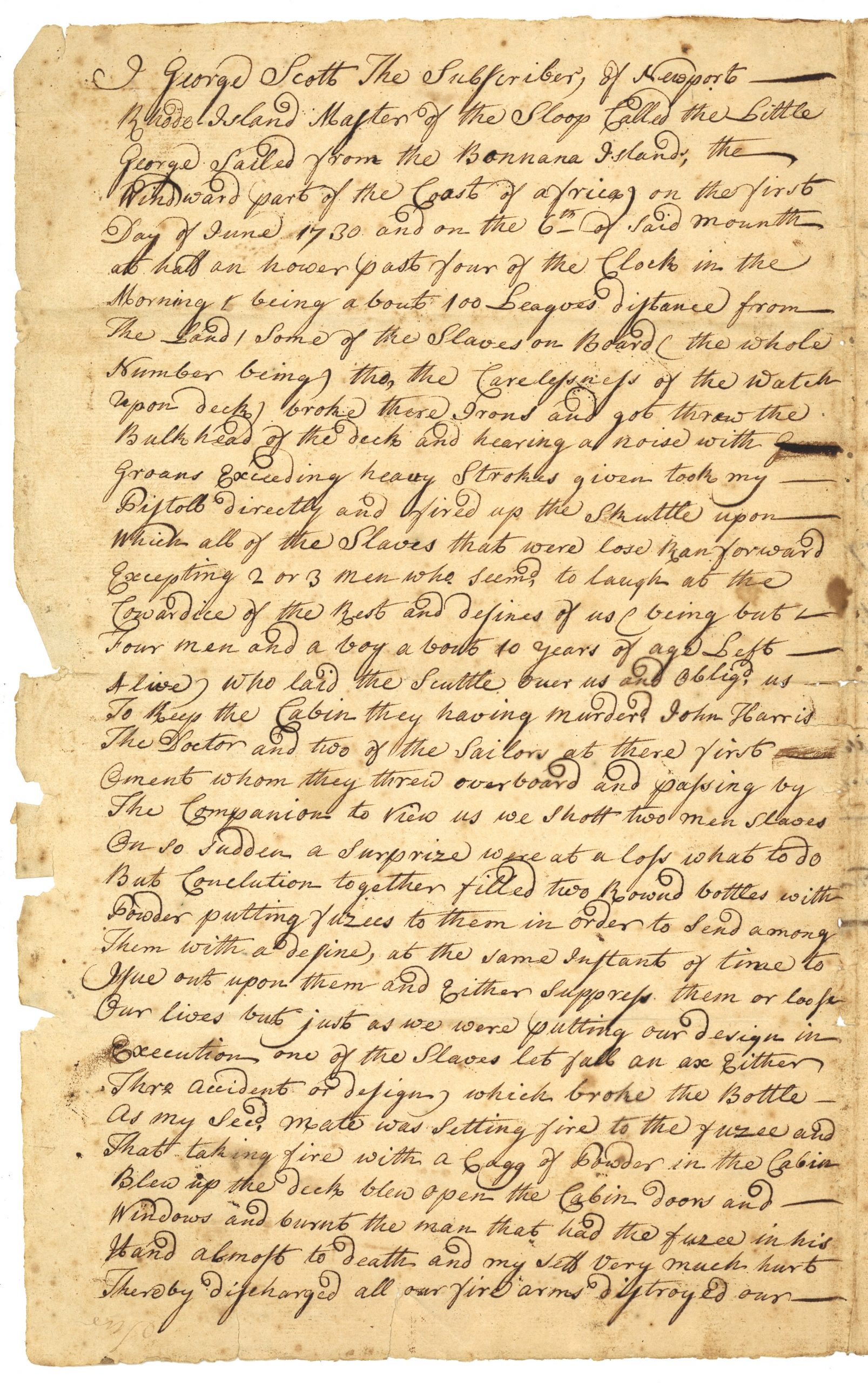

Narrative of Slave Revolt on Ship off Africa

Read about stories of enslaved Africans fighting back on slave ships here

Rhode Islanders played a central role in the American slave trade during the 1700s. A total of about one thousand slave-trading voyages, or one-half of all American slaving voyages, sailed from Rhode Island to the coast of Africa, in what has been called the triangular trade. Rum was exchanged for captives in Africa, captives were traded for slave-grown sugar and molasses in the West Indies, and the molasses was processed in New England to make rum. Newport was the primary slaving port until the Revolution, after which Bristol assumed preeminence.3For Rhode Island’s role in the American slave trade, see J. Stanley Lemons, “Rhode Island and the Slave Trade,” Rhode Island History 60:4 (Fall 2002), 95-104, Jay Coughtry, Notorious Triangle: Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade 1700-1807 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981), especially the overview on 6, Leonardo Marques The United States and the Transatlantic Slave Trade to the Americas, 1776-1867 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), and Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York: New York University Press, 2017)

The exploitation of enslaved people as laborers in Rhode Island made a substantial contribution to the colony’s economy in many ways, as the enslaved population grew after 1700. While Rhode Island did not have the largest absolute number of enslaved people in New England, it had the largest percentage of Africans, nearly all of them enslaved, among its residents—6% of the population in 1708 had risen to an astonishing 11.5% by 1755, when only four out of twenty-five cities and towns in the colony reported fewer than twenty enslaved people in its population.4The four towns were Gloucester with 7 enslaved people, Cumberland with 13 enslaved people, Coventry with 16 enslaved people, and Scituate with 18 enslaved people5Evarts B. Greene, and Virginia D. Harrington. American Population before the Federal Census of 1790. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1966 In South Kingstown, about 30% of the residents were enslaved laborers, a number comparable to the percentage in Maryland and North Carolina at that time. The presence of such a large percentage of enslaved people distinguished Rhode Island from the other New England colonies, where Africans never constituted more than 3.2% of the population.

If Rhode Island anchored the American slave trade, slaving and trade with the slave-based economies of the Caribbean and the southern American colonies strengthened the commercial maritime development of Rhode Island. Virtually every commercial enterprise was in some way connected with the slave trade. Banking and insurance, ship-building and sail-making, and the production of manufactured goods such as iron, spermaceti candles, barrels, rope, and tobacco (Rhode Island grew what was universally regarded as rather poor-quality tobacco) connected Rhode Island to the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The trade in chocolate, loaf sugar, mahogany, and Dutch bills of exchange connected to the slave trade. And, the distilling of rum, the trade in rum distilled by other manufacturers, and the exchange of rum for African captives were part of the extensive Rhode Island maritime commerce connected tightly with slavery and the slave trade. While the purchase, transportation, and sale of captive Africans was the principal occupation of some businessmen like James D’Wolf of Bristol, for others it was just one of many commercial ventures linked in some other way to the slave trade. Even for the so-called “middling sort”—artisans, shopkeepers, and other skilled laborers and tradesmen—purchasing a few shares of a slaving voyage was a common investment.6Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York: New York University Press, 2016), especially 10-60; Rachel Chernos-Lin, “The Rhode Island Slave Traders: Butchers, Bakers and Candlestick-Makers,” Slavery & Abolition 23:3 (December 2002), 21-38; and Joanne Pope Melish. Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and ‘Race’ in New England, 1780-1860. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1998

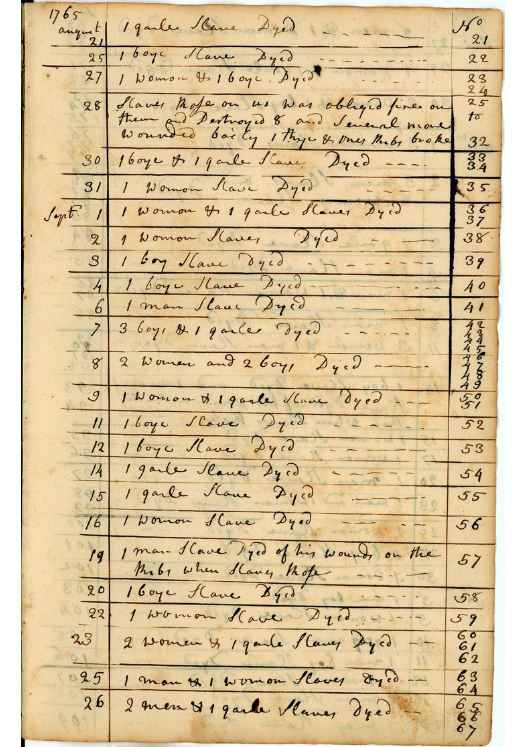

Account of the Slave Ship Sally

Read about the voyage of the slave ship Sally here

Enslaved Labor across the Colony

Another one-quarter of the enslaved people in Rhode Island lived in the port cities of Newport, Bristol and Providence, where they performed the skilled and unskilled labor that enabled busy ports to operate efficiently and economically—transporting goods to and from manufactories to the wharves, loading and unloading boats—as well as performing garden and household labor. Some of them also worked in the numerous Rhode Island distilleries—twenty-two in Newport alone. Enslaved laborers constituted nearly one-third of the total population in certain Rhode Island cities and towns by the mid-eighteenth century. During the colonial period, it also became increasingly common for White families who moved from the coast into smaller towns and outlying farms on the northwestern edge of the colony—the “frontier” in the eighteenth century—to bring one or two enslaved laborers with them to perform household labor and farm work, often alongside members of the White family.7Lorenzo Johnston Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England (New York: Atheneum, 1968), 25-26; 85-88; 83

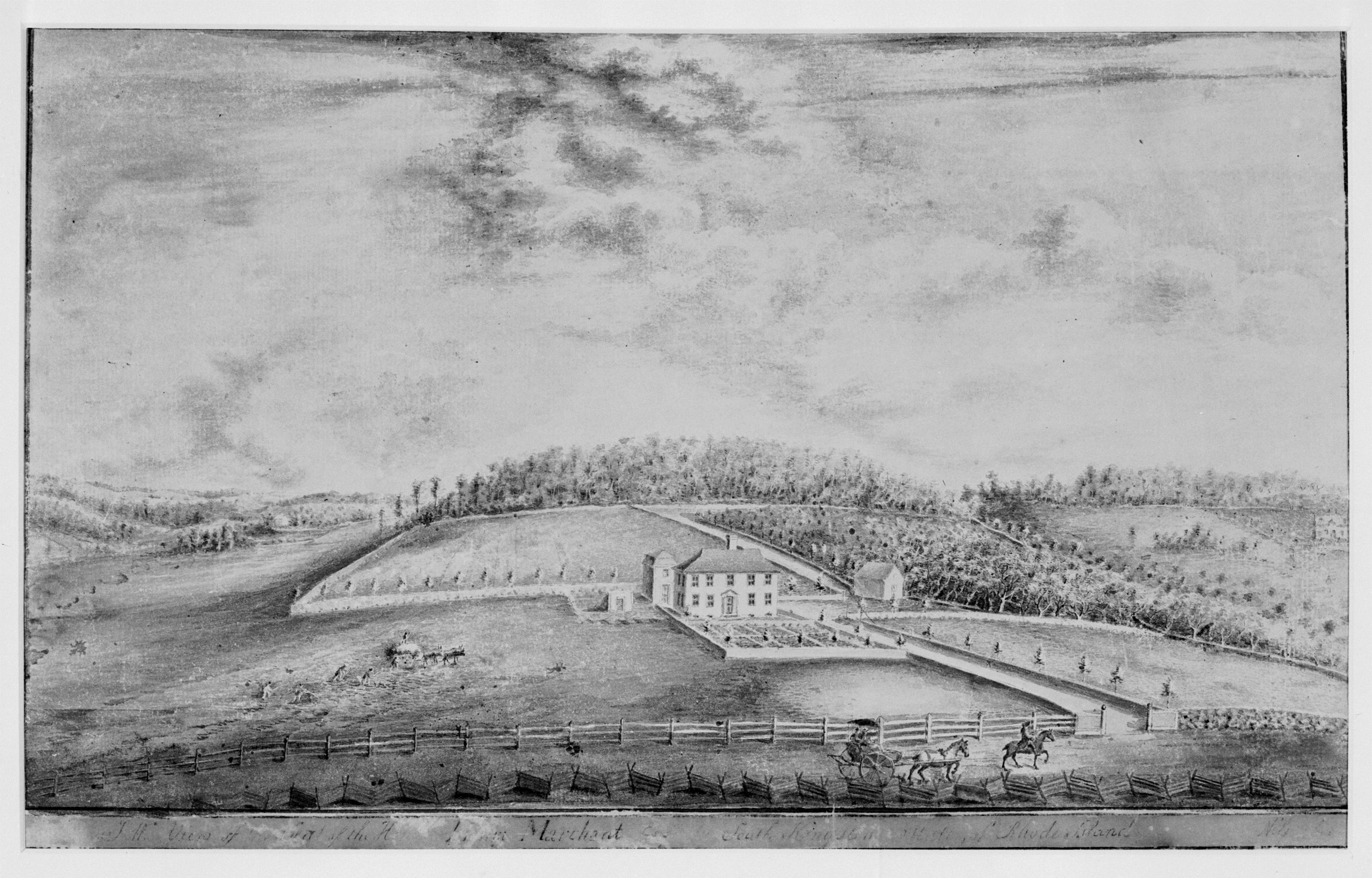

The Provisioning Trades and the Narragansett Planters

The most substantial contribution made by the labor of enslaved people in Rhode Island to the growth of its maritime economy was their production of agricultural commodities for export to the slave colonies in the British West Indies. About one-third of the enslaved population in 1741, declining to one-quarter by 1755, lived in “the Narragansett country”—the area of large agricultural plantations in South Kingstown, North Kingstown, Charlestown, and Westerly. There they performed all of the skilled and unskilled labor associated with raising sheep, cattle, and horses (the now extinct Narragansett pacer), and growing grain, all for the so-called “coasting” or provisioning trades to the slave colonies of the American South and the West Indies. Enslaved women worked in dairies to produce butter and cheese, other labor-intensive and lucrative export products. Enslaved men, women, and children performed the farm and domestic labor that sustained both the planter families who lived in Narragansett and the enslaved families themselves.8Clark-Pujara, Dark Work, 24-28; Robert K. Fitts, Inventing New England’s Slave Paradise: Master/Slave Relations in Eighteenth-Century Narragansett, Rhode Island (New York & London, Garland Publishing, Inc., 1998), 76-78

South West View of Seat of Henry Merchant

Read about the plantations in South County here

Slavery and the Law

Although the condition of permanent, heritable enslavement was not explicitly reduced to the status of “chattel” until 1755, a body of laws regulating the institution of slavery and the behavior of enslaved people grew up quite quickly. Some of these were designed to safeguard the public order against “unruly” enslaved people and seem to reflect an awareness that holding an increasing population of people in bondage against their will and making them perform hard labor with no compensation and little hope of liberty was likely to produce resistance. Others seemed to be aimed at simply curtailing behavior that might offer those enslaved the illusion and pleasures of freedom. A 1704 law forbade enslaved people to be out after 9 pm on penalty of whipping and made entertaining them a crime, and a 1751 law extended the entertainment ban to “Indian, Negro, or Mulatto servants or slaves” and explicitly outlawed selling them liquor. The following year, an act was passed to break up “disorderly” homes of people of color.9These laws were repealed sometime between 1798 and 1810. Both of them were still on the books in the 1798 Digest of the Public Laws of the State of Rhode Island, but both were no longer listed in the 1810 Supplement to the Digest of the Public Laws of the State of Rhode Island To prevent sea captains from luring African enslaved men, who apparently made exceptionally good mariners, onto their boats to become crew members, a 1757 law made carrying enslaved people out of the colony without the consent of their masters a crime punishable by a fine of £26. All of these regulations reinforced the obvious fact that slaves were people, not chattel.

At the same time that their humanity and will were being recognized in Rhode Island law, enslaved people were being taxed as property nonetheless. In 1708 the Rhode Island General Assembly passed an import tax of £3 per enslaved person, the income to be used to repair roads and bridges. The law was amended in 1729 to split the use of the income between roads and bridges.10For laws governing slavery in Rhode Island, see Acts and Laws of the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (Newport: Samuel Hall, 1767) and John Russell Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony/State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (Providence: A.C. Greene, 1856-1865), ten volumes covering 1636-1792 and unnumbered volumes covering 1792-1805

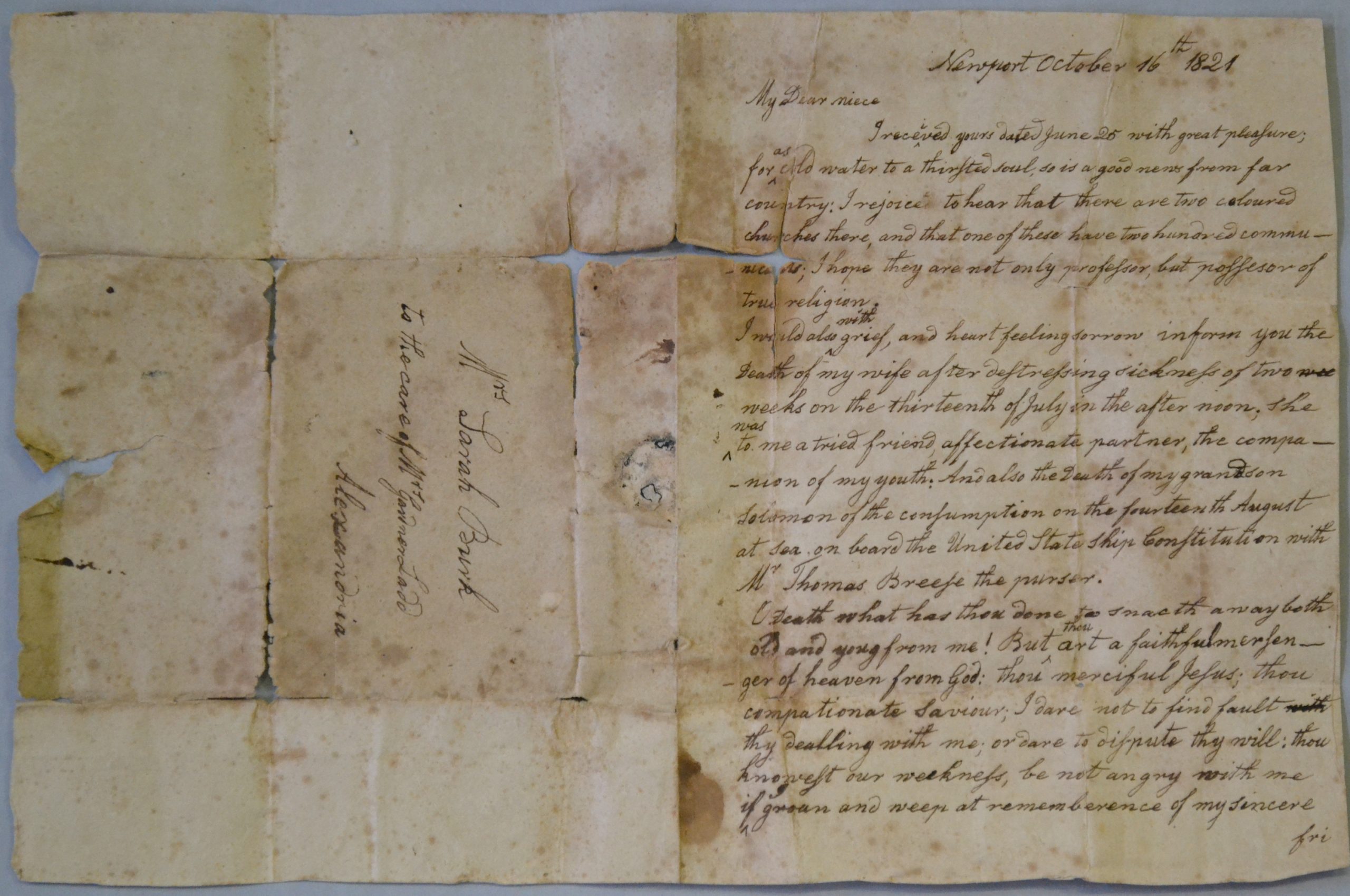

Newport Gardner

Read about Newport Gardner here

The Creation of an African American Culture

Legislators may have tried to muddle together the personhood and property status of the enslaved in law, but enslaved Africans themselves were never confused about their status or their entitlement to the full range of human rights. The personhood of Rhode Island enslaved people was protected and reinforced by the rich, distinctive culture they fashioned out of remnants of their original African cultures and the culture they found in the English colonies.

For the first hundred years, most enslaved Africans came to Rhode Island by way of the Caribbean. Because the brutal plantation labor of the Caribbean and southern colonies demanded a constant supply of the physically strongest captives, enslavers usually brought their cargoes directly from Africa to the Caribbean and sold the most desirable laborers there. Younger or weaker captives and those “seasoned” in the Caribbean who had become weakened or injured under that brutal work regime were often brought to New England to perform the less physically demanding labor required there. However, it is important to note that less physically demanding labor does not mean “easy” or “easier” labor. Being an enslaved laborer, regardless of where the work was being done, required huge amounts of physical, mental, and emotional work without any compensation. Working for and living with the English in the Caribbean, and working in small numbers in the households of Whites where they often were relatively isolated from each other, many enslaved people in New England became relatively acculturated to English ways.11Ira Berlin, “Time, Space, and the Evolution of Afro-American Society on British Mainland North America,” The American Historical Review 85:1 (February 1980), 49-53

Beginning in the 1750s, however, slave ships began bringing African captives directly from Africa to New England, re-Africanizing the culture of enslaved people and the small community of free Blacks. This re-Africanization can be seen in the increased appearance of West African names such as “Cuffe” and “Gambia” among enslaved New Englanders, and in the emergence of West African-based festivals that Whites dubbed “Negro elections,” unaware of their actual origins and meaning. These festivals were held annually on the third Saturday in June and continued until the 1850s. Enslaved men who ran for “Negro Governor” persuaded their masters to provide food and drink and to lend them clothing and even horses, inspiring competition among owners for the honor of having one of their enslaved men elected Governor. From such festive practices to more everyday matters such as foodways, religious practices, and folktales, the syncretic Anglo-African culture of enslaved and free Blacks in New England was enriched and strengthened by a new infusion of African elements.12For the retention of African culture by enslaved Africans in New England, see William D. Piersen, Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), especially 117-128 and 57-58

The Gradual End of Slavery in Rhode Island

Although slavery became a widespread institution in Rhode Island, even in the early years, Rhode Islanders clearly were troubled by certain aspects of it and attempted to curb its development. A 1652 law made it illegal for any person, black or White, to be “bound” longer than ten years, and another in 1675 forbade the enslavement of Indians. These laws were widely ignored, however. Despite the enactment of such laws, the economic profits reaped from the labor of the enslaved, as well as the wealth gained by Rhode Islanders’ participation in the Atlantic slave trade, solidified the Ocean State’s commitment to lifelong bondage.

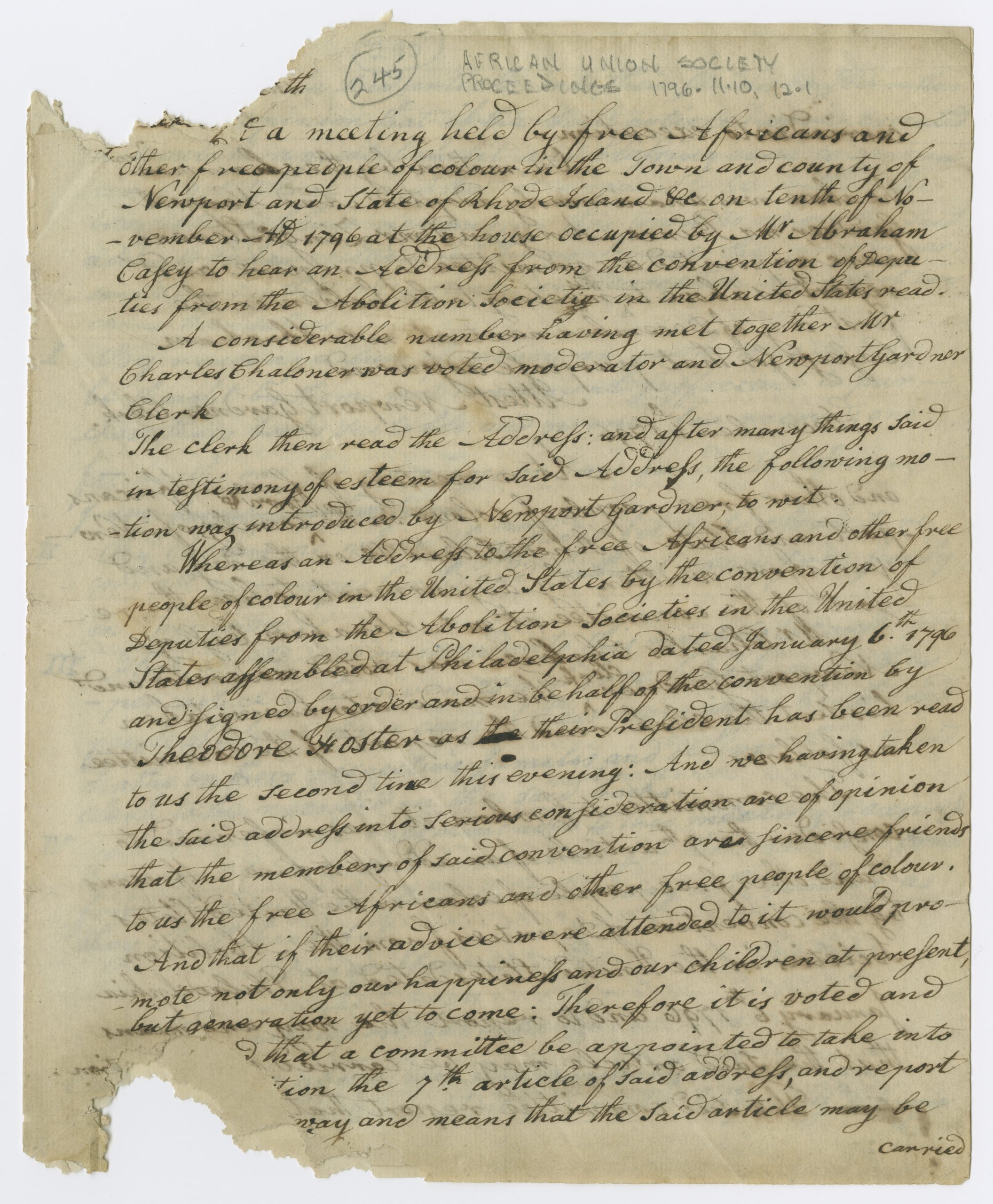

African Free Union Society Meeting

Read about free Black communities here

Throughout the eighteenth century, a slowly growing number of enslaved people became legally free by being emancipated individually for various reasons. Initially, most continued to live in the households of their former owners or other Whites, where they worked as domestics and farm laborers, but gradually a growing number began to form independent households. Some also formed households with Native people and lived independently or on Narragansett tribal land in Charlestown.13For relations between free African Americans and the Narragansett people in Rhode Island in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, see Ruth Wallis Herndon and Ella Wilcox Sekatau, “The Right to a Name: Narragansett People and Rhode Island Officials in the Revolutionary Era,” Ethnohistory 44:3 (Summer 1997), 433-62

Although most African Americans in Rhode Island remained enslaved through the 1760s, the free Black population continued to grow steadily, despite statutes passed in 1728, 1765, and 1775 to curb individual manumissions by requiring the owners or the enslaved individuals themselves to post bond. The bond would be used to support those who had been freed in the event that they could not support themselves and became indigent, or dependent on public aid to survive. Nonetheless, individual manumissions increased, partly in response to the steadily slowly growing criticism of the principle of trading in humans and owning property in persons.

By 1774, enough Rhode Islanders had been convinced of the evils of the slave trade that the assembly was able to pass a law making it illegal for any Rhode Island citizen to bring enslaved persons into the colony unless they posted bond to bring them out again within one year.14The colony of Connecticut passed a similar bill in the fall of 1774. Some individual Massachusetts towns passed ordinances forbidding the importation of enslaved people around the same time. Pennsylvania passed a law against further importation of enslaved people as part of its 1780 Gradual Abolition Act

All enslaved people brought into the colony in defiance of the law, except those accompanying travelers, would be set free. Intended to discourage the slave trade, this law merely caused Rhode Island slavers to sell their African captives in other ports and bring their profits home to Rhode Island.15For the steps taken to end northern slavery, see Arthur Zilversmit, The First Emancipation: The Abolition of Slavery in the North (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967), especially 16-124 for Rhode Island

The coming of the American Revolution, however, eroded the institution of slavery itself in several important ways. One was the emancipation of enslaved men who served as soldiers. A critical shortage of troops caused the RI legislature in 1778 to pass a bill permitting enslaved men to enlist in exchange for soldiers’ benefits and freedom after at least three years of service; their owners would be compensated for their value up to £120 and would no longer be liable for the support of their former slaves if they were to become indigent after the war. By essentially “buying” enslaved men from private citizens, it could be argued that Rhode Island was, in fact, assembling a mercenary unit. About two hundred men of color, including about ninety enslaved men emancipated under the 1778 law and another forty-four who enlisted after its passage, were mustered into the Rhode Island First Regiment. The regiment repelled three assaults by veteran Hessian troops at the Battle of Rhode Island in Portsmouth on August 29, 1778. In 1780, it was merged with the Second Rhode Island to form the Rhode Island Regiment, the first integrated regiment in the Continental Army. The Rhode Island regiment served in several other engagements, including at Yorktown, before being disbanded in June of 1783.16See Robert A. Geake and Lorén M. Spears, From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2016)

The Revolutionary rhetoric of natural rights also moved public opinion slowly in the direction of emancipation. In 1783, noting that slavery was incompatible with the “Rights of Man,” the legislature passed a post nati (after birth) emancipation bill making all children born to enslaved women after March 1, 1784, free at 18 years of age if female and 21 years of age if male. The original bill required the towns to support these children until they reached the age of freedom, with the assumption that the towns would recuperate the expense by binding them out to service. But the towns objected strenuously, and the bill was amended only eight months later to give the owners of the enslaved mothers of newborns responsibility for their support—and, more importantly, entitlement to their labor—until they reached the age of maturity and were thus eligible for manumission. The day after the bill went into effect, what had changed? Enslaved people remained enslaved. Children born to enslaved women would not be free for nearly twenty years. The only real, immediate change inaugurated by the 1784 bill was to provide an incentive for individual manumission by relieving owners who freed enslaved people between twenty-one and forty (amended by the end of the year to thirty) years of age of further financial responsibility for them, should they become indigent.17Thirty-two enslaved people were manumitted in the city of Providence in the five years following the passage of the 1784 act, however, many of these enslaved people were considered to be beyond their prime working years and were being maintained by their owners solely to avoid having to post bond for them in order to be freed from supporting them. The new law freed owners from the certain expense they would incur if their enslaved person reached forty (then thirty) still enslaved by them

Effectively, although Rhode Island’s political leadership now began calling Rhode Island a “free state,” nothing had changed after March 1, 1784. Enslaved people remained enslaved, and their children remained bound in enforced servitude for eighteen to twenty years. But gradually—as slave owners became less willing to offer rewards to recover enslaved people who ran away, and as more Rhode Islanders became convinced that slavery was wrong and manumitted them individually—slavery came to an end. The first Federal census in 1790 reported 948 enslaved people in Rhode Island and still over 100 people in the 1810 census. Not until 1842 did a new State Constitution make slavery illegal in Rhode Island. There were only five enslaved people listed in the Rhode Island census of 1840. There may have been a few more who were still enslaved but being maintained by owners because they were very elderly. Fifty-eight years after the inception of a gradual emancipation that made Rhode Island a “free state,” all enslaved people in Rhode Island were officially, legally free.18Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and ‘Race’ in New England, 1780-1860). Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998. 67-76

The Struggle to Enact Black Freedom

Meanwhile, by 1820 free people of color faced increasing job discrimination, rhetorical attack, and physical violence. Often unable to find regular employment, free people of color in Providence and other Rhode Island towns were increasingly rounded up in small groups and interrogated by Town Councils about their “legal settlement”—whether they were legally entitled to live in the town where they were living, or whether they “belonged” in another town where they had been born, indentured, or enslaved. The purpose was to remove free Black “strangers” who might someday require “town charity.” But in fact, many of these people had supported themselves successfully for years in towns they now regarded as home. Others were reluctant to return to towns from which they had fled illegally from enslavement. Nonetheless, these people were often summarily warned out, carted away physically, and whipped if they returned.19See Ruth Wallis Herndon, Unwelcome Americans: Living on the Margin in Early New England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 1-26, for a general description of the warning-out process. The rest of the book provides forty stories of individual transient people warned out of colonial Rhode Island

Meanwhile, a small but growing middling and professional class of free Blacks in Providence, Newport, and other towns were able, through perseverance and hard work, to establish churches, schools, successful businesses, and other institutions. But such achievements were often ridiculed by Whites in satiric broadsides. In 1822, Black men were disfranchised by statute in Rhode Island, having once been eligible to vote if they met a property qualification required of all voters. In Providence, mobs of Whites attacked Black communities known as Hardscrabble in 1824 and Snowtown in 1831, two of more than a hundred mob attacks on communities of color in the North in the antebellum period.20Melish, Disowning Slavery, 171-182; 204-08; Robert J. Cottrol, The Afro-Yankees: Providence’s Black Community in the Antebellum Era (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982) The White sailors and residents of Providence who provoked the two attacks were not punished, and Black victims were not compensated for their loss of property. The events were so traumatic, that some families left the area, and some even left the country.21Christy Clark-Pujara, “In Need of Care: African American Families Transform the Providence Association for the Benefit of Colored Orphans during the Final Collapse of Slavery, 1839-1846,” Journal of Family History. September 12, 2019. 299-300

African Americans in Rhode Island persevered, striving to overcome discrimination, achieve equal opportunity and respect, and establish a strong voice in Rhode Island affairs. Black men regained the right to vote with the adoption of a new state constitution in 1842. Nonetheless, it was 1866 before African American community leaders were able to persuade the Rhode Island General Assembly to ban segregation in public schools statewide. Struggles against other forms of discrimination continue to the present day.22Clark-Pujara, Dark Work, 136 and 142-43

Terms:

Negro: an old term used to describe people of African descent. Although some older generation African Americans still self-identify with this term, it has been used derogatorily by the White majority population for hundreds of years and is not appropriate to use in writing or in speech. You may come across the term in research or in old documents

Heritable: inherited through the bloodline. Here, we are talking about slavery that was inherited from mother to children

Chattel: personal property. Here, we are discussing people being treated like property by enslavers while their status as property is passed on to their children. This differs from other forms of slavery where a person may be enslaved for a period of time to pay off a debt or as a captive of war and where a person’s status can change and is not passed on to their children

Mulatto: an old racial classification used to describe a person with one White parent and one Black parent

Enslavers: the people imposing slavery onto other people

Re-Africanizing: in the case here, people taken from Africa and living in Rhode Island (and other areas) reinstated customs and traditions or re-created customs and traditions in their new place in an attempt to maintain a sense of identity. Since enslaved people came from various cultural backgrounds in Africa, they blended and re-created new cultures in the Americas

Indigent: a poor person or a person unable to support themselves. Cities and towns wanted to avoid having to pay to help those without support. An argument against abolition of slavery was that those formerly enslaved would not be able to take care of themselves and would need support from their town of residence

Mercenary: fighting for money rather than for a political reason. The author here is arguing that enslavers who allowed those they enslaved to be bought to fight the war did so, at least in part, out of monetary interest rather than in support for what the war stands for

Warned out: made to leave town because of some wrongdoing according to the town’s council

- 1For these and other cited statistics on the enslaved population in Rhode Island, see Evarts B. Greene and Virginia D. Harrington, American Population before the Federal Census of 1790 (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1966), 61-69 and Ira Berlin, Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves (Cambridge, MA, and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003), Table I, 272

- 2Margaret Ellen Newell, Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2015), 57, 158-59; 51; and Margaret Ellen Newell, “The Changing Nature of Indian Slavery in New England, 1670–1720,” in Reinterpreting New England Indians and the Colonial Experience, edited by Collin Calloway and Neal Salisbury (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 2003), pp. 126-136. [link]

- 3For Rhode Island’s role in the American slave trade, see J. Stanley Lemons, “Rhode Island and the Slave Trade,” Rhode Island History 60:4 (Fall 2002), 95-104, Jay Coughtry, Notorious Triangle: Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade 1700-1807 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981), especially the overview on 6, Leonardo Marques The United States and the Transatlantic Slave Trade to the Americas, 1776-1867 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), and Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York: New York University Press, 2017)

- 4The four towns were Gloucester with 7 enslaved people, Cumberland with 13 enslaved people, Coventry with 16 enslaved people, and Scituate with 18 enslaved people

- 5Evarts B. Greene, and Virginia D. Harrington. American Population before the Federal Census of 1790. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1966

- 6Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York: New York University Press, 2016), especially 10-60; Rachel Chernos-Lin, “The Rhode Island Slave Traders: Butchers, Bakers and Candlestick-Makers,” Slavery & Abolition 23:3 (December 2002), 21-38; and Joanne Pope Melish. Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and ‘Race’ in New England, 1780-1860. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1998

- 7Lorenzo Johnston Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England (New York: Atheneum, 1968), 25-26; 85-88; 83

- 8Clark-Pujara, Dark Work, 24-28; Robert K. Fitts, Inventing New England’s Slave Paradise: Master/Slave Relations in Eighteenth-Century Narragansett, Rhode Island (New York & London, Garland Publishing, Inc., 1998), 76-78

- 9These laws were repealed sometime between 1798 and 1810. Both of them were still on the books in the 1798 Digest of the Public Laws of the State of Rhode Island, but both were no longer listed in the 1810 Supplement to the Digest of the Public Laws of the State of Rhode Island

- 10For laws governing slavery in Rhode Island, see Acts and Laws of the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (Newport: Samuel Hall, 1767) and John Russell Bartlett, ed., Records of the Colony/State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (Providence: A.C. Greene, 1856-1865), ten volumes covering 1636-1792 and unnumbered volumes covering 1792-1805

- 11Ira Berlin, “Time, Space, and the Evolution of Afro-American Society on British Mainland North America,” The American Historical Review 85:1 (February 1980), 49-53

- 12For the retention of African culture by enslaved Africans in New England, see William D. Piersen, Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), especially 117-128 and 57-58

- 13For relations between free African Americans and the Narragansett people in Rhode Island in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, see Ruth Wallis Herndon and Ella Wilcox Sekatau, “The Right to a Name: Narragansett People and Rhode Island Officials in the Revolutionary Era,” Ethnohistory 44:3 (Summer 1997), 433-62

- 14The colony of Connecticut passed a similar bill in the fall of 1774. Some individual Massachusetts towns passed ordinances forbidding the importation of enslaved people around the same time. Pennsylvania passed a law against further importation of enslaved people as part of its 1780 Gradual Abolition Act

- 15For the steps taken to end northern slavery, see Arthur Zilversmit, The First Emancipation: The Abolition of Slavery in the North (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967), especially 16-124 for Rhode Island

- 16See Robert A. Geake and Lorén M. Spears, From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2016)

- 17Thirty-two enslaved people were manumitted in the city of Providence in the five years following the passage of the 1784 act, however, many of these enslaved people were considered to be beyond their prime working years and were being maintained by their owners solely to avoid having to post bond for them in order to be freed from supporting them. The new law freed owners from the certain expense they would incur if their enslaved person reached forty (then thirty) still enslaved by them

- 18Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and ‘Race’ in New England, 1780-1860). Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998. 67-76

- 19See Ruth Wallis Herndon, Unwelcome Americans: Living on the Margin in Early New England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 1-26, for a general description of the warning-out process. The rest of the book provides forty stories of individual transient people warned out of colonial Rhode Island

- 20Melish, Disowning Slavery, 171-182; 204-08; Robert J. Cottrol, The Afro-Yankees: Providence’s Black Community in the Antebellum Era (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982)

- 21Christy Clark-Pujara, “In Need of Care: African American Families Transform the Providence Association for the Benefit of Colored Orphans during the Final Collapse of Slavery, 1839-1846,” Journal of Family History. September 12, 2019. 299-300

- 22Clark-Pujara, Dark Work, 136 and 142-43