Narrative of Slave Revolt on Ship off Africa

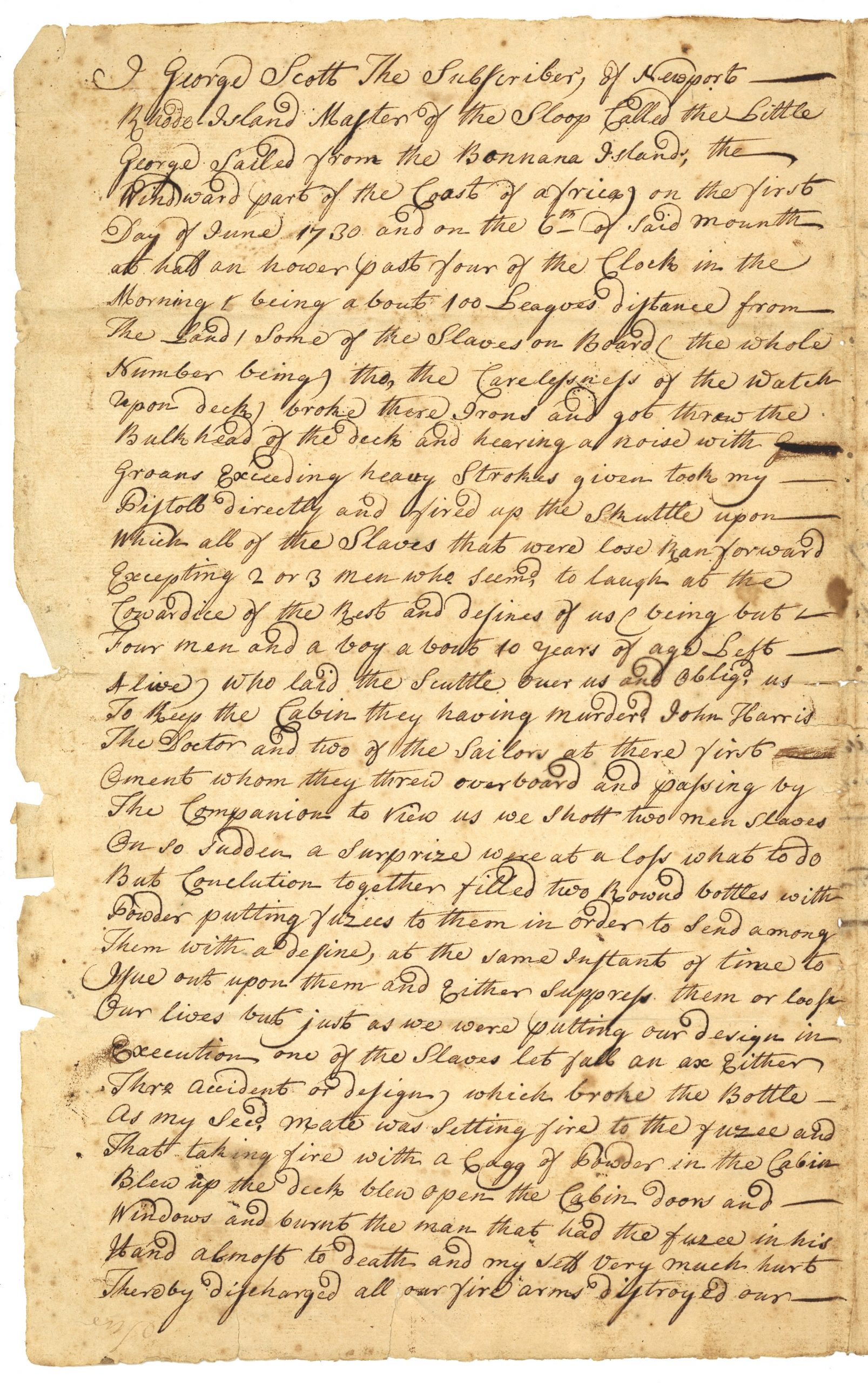

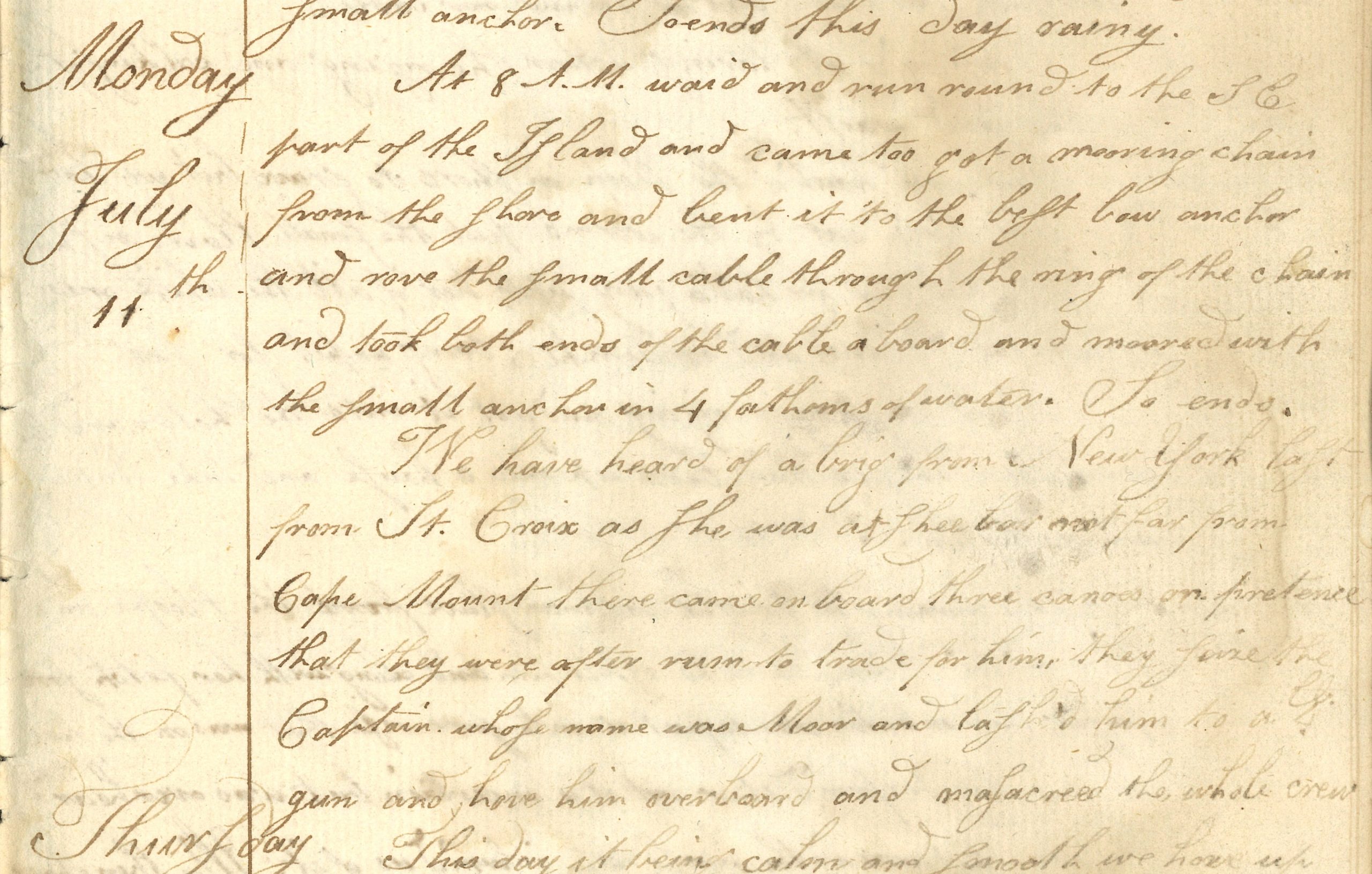

The image to the left is a page from the testimony of Captain George Scott who lived to tell the tale of the enslaved Africans on his ship, Little George. In 1730, they slipped out of their irons and fought back, locking Scott and his crew in the cabin while they sailed back to Africa, abandoned the ship, and escaped.

Attempts at Freedom: Fighting Back on Rhode Island’s Slave Trading Ships

Essay by Jennifer Galpern, Research Services Manager, Rhode Island Historical Society

One of the ways enslaved Africans attempted to escape was through uprisings aboard the ships on which they were held captive. Documents in archives reveal that ship owners purchased insurance in preparation for possible uprisings, and newspapers published articles about uprisings.1Elizabeth Donnan. Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America. Vol. 1. (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1930.), p. 457-464 Enslavers even noted where the so-called “ideal” slaves could be found: “Slaves differ in the goodness; those from the Gold Coast are accounted best, being cleanest limbed, and more docile by our Settlements than others; but then they are, for that very reason, more prompt to Revenge, and murder the Instruments of their Slavery, and also apter in the means to compass it.”2Donnan, Vol. 2, p. 282 Enslavers often shared where to obtain the “docile” captives. While there are many stories of uprisings, in most cases, enslaved Africans were not able to take over the ship. These stories show how enslaved people, though kidnapped and in chains, practiced agency and fought for their own self-preservation.

In early 1730, Captain George Scott sailed out of Newport on the sloop Little George, a ship owned by merchant Godfrey Malbone, en route to Africa. Scott had sailed previously to Africa on another of Malbone’s ships, the brig Charming Betty in 1728.3Kenneth Scott. “George Scott, Slave Trader of Newport.” The American Neptune. Vol. 12, No. 3, July 1952. Peabody Museum of Science, Salem, Mass. p. 222-228 While nothing is known about that earlier voyage, the story of the Little George is well documented by Captain George Scott in records housed at the Rhode Island Historical Society.4MSS 17 Harris Family Papers, Box 2 Folder: 1730, Narrative of Slave Revolt on Ship off Africa

In June 1730, Scott sailed from the Guinea Coast with a cargo of 96 captured Africans. Many days into the voyage, several African men slipped out of their irons and attacked the crew. Using weapons seized on the ship, the Africans killed three of the watchmen who were on deck. Scott and his crew tried to fight back but were subdued and forced into the cabin, where they were imprisoned. For several days the Africans controlled the ship and were able to sail it back to the Sierra Leone River, an estuary of the Atlantic Ocean on the west African coast. The Africans made it to shore, abandoning the ship and leaving the crew, still barricaded in the cabin and alive, having survived for nine days eating only raw rice.5Donnan, Vol. 3, p. 121

More fortunate than other ship Captains in similar circumstances, George Scott survived the revolt, lived to tell his tale, and in 1732 he married Mary Neargrass, and they had three children. The document pictured is Captain George Scott’s testimony of the uprising. [Click here to view George Scott’s entire testimony with typed transcription]. Scott continued to participate in the slave trade until the spring of 1740. While he was master of the ship Patience, he wrote a letter dated June 13, 1740, near the coast of Antigua, which was the last anyone heard from him. He was declared dead in 1744 following an appeal to the courts by his widow so that she could remarry.

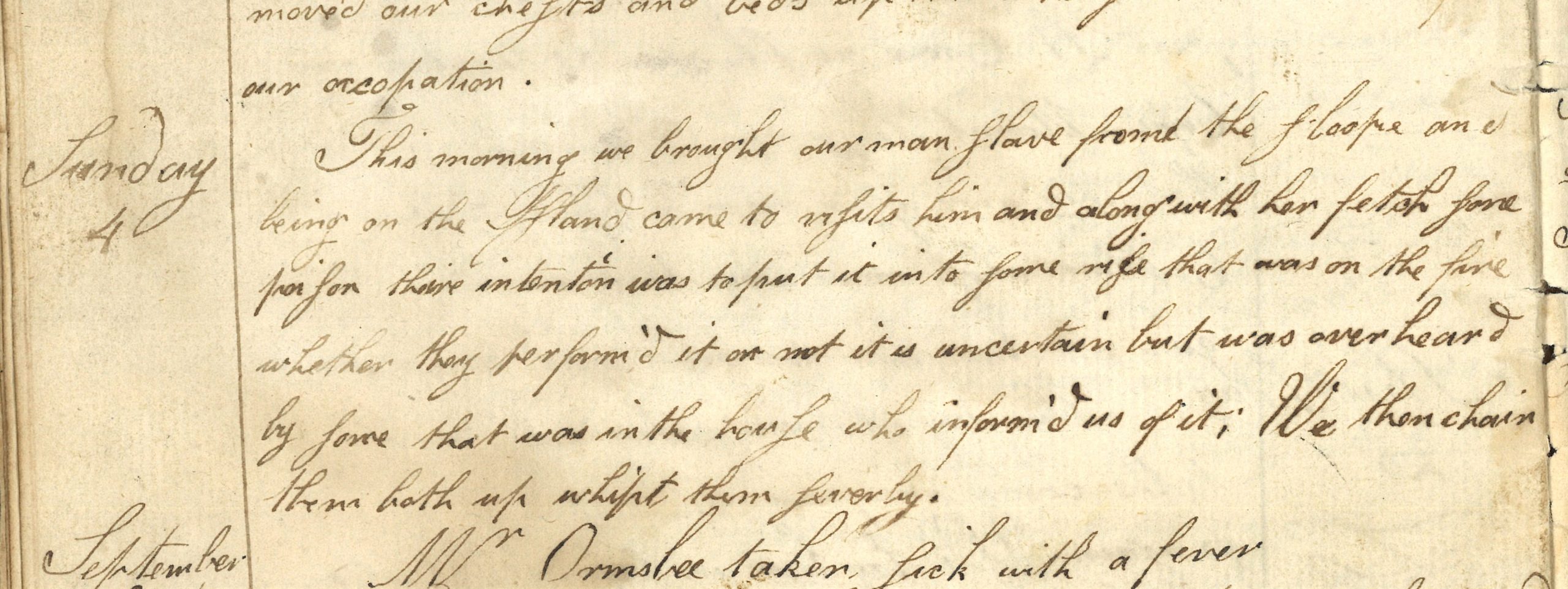

The Rhode Island Historical Society Ship Logs Collection6MSS 828 includes a log of the slave ship Dolphin. This diary, kept by an unknown seaman from 1795 to 1797, is one of the few surviving eyewitness accounts of a slaving voyage. From the documentation, the voyage seems to have been a failure. The crew initially set out in the ship Dolphin, changed over to the sloop Rising Sun in St. Thomas, and upon reaching Africa, quickly took on 21 enslaved Africans. The ship then suffered serious damage in a tornado and sat on an island for almost a year, attempting repairs while the captain traveled to the mainland to buy more enslaved Africans. During this period, two enslaved Africans were whipped for plotting to poison the crew’s rice.

On September 4, 1796, the author wrote: “This morning we brought our man slave from the Sloop and being on the island came to visit him and along with her fetch some poison their intention was to put it into some rice that was on the fire whether they perform’d it or not it is uncertain but was overheard by some that was in the house who inform’d us of it; we then chain them both up whipt them severely.” The Rising Sun was eventually pronounced unfit for sailing, and the diarist joined on with the crew of a Boston-bound sloop Fame to begin his journey home.

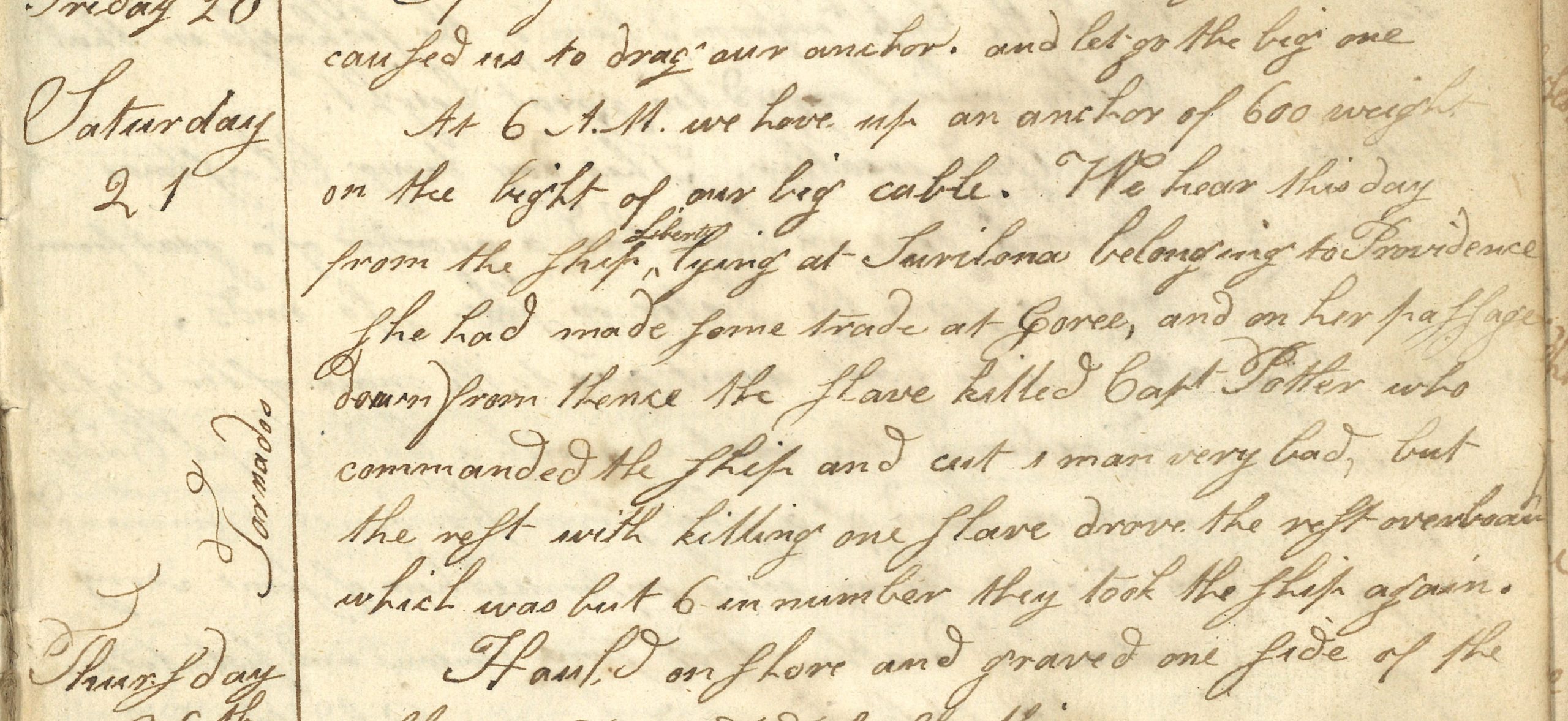

Three additional slave revolts on other ships are described in this diary through hearsay. The uprisings were on the ship Liberty in 1795 and a ship from New York on which a Captain Moore and his crew were all massacred in 1796.

On November 21, 1795, the author wrote: “We hear this day from the Ship Liberty lying at Saurilona belonging to Providence. She had made some trade at Goree, and on her passage down from thence the slave killed Capt. Potter who commanded the ship and cut a man very bad, but the rest with killing one slave drove the rest overboard which was but 6 in number they took the ship again.” The story is that Captain Abijah Potter allowed the enslaved people to roam around the main deck unshackled and unguarded. They discovered an ax and killed Potter and a mate before the rest of the crew were able to reach the arms chest and subdue them.

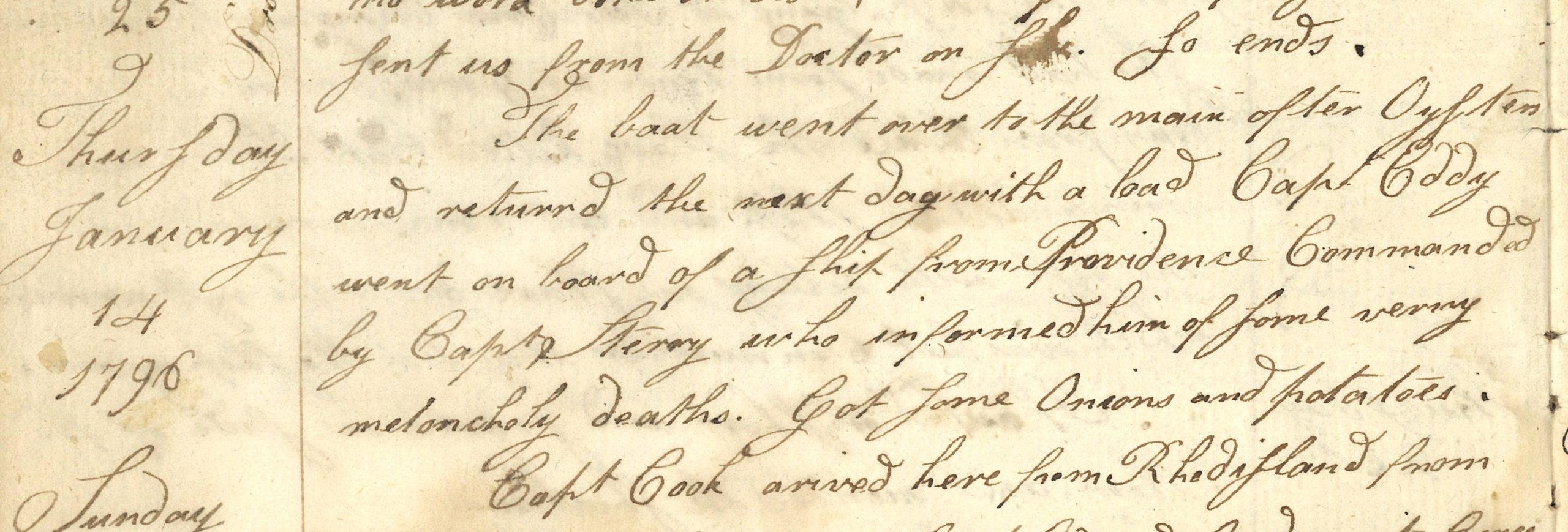

On January 14, 1796, the author wrote: “The boat went over to the main after oysters and returned the next day with a load. Capt. Eddy went on board a ship from Providence commanded by Capt. Sterry, who informed him of some very melancholy deaths. Got some onions and potatoes.” Captain Sterry was saved from an uprising by the warning of an African cabin boy who heard the enslaved people free themselves from their leg irons and attempt to attack the crew on deck. Even though the crew had a warning, the enslaved Africans fought hard for their freedom, and it was a brutal battle. Four of them were killed and many wounded before the crew was able to take back control of the vessel.

On July 11, 1796, the author wrote: “We have heard of a brig from New York last from St. Croix as she was at Sheeboar not far from Cape Mount there came on board three canoes on the pretense that they were after rum to trade for him, they seized the Captain whose name was Moor and lashed him to a G gun and hove him overboard and massacred the whole crew.” It is unclear from the passage what happened to the enslaved people on board. Perhaps other archives elsewhere hold the answer.

It is important to bear in mind that the records written on a slave trading ship are from the perspectives of the enslavers, whether it be the captain or members of the crew. The enslaved were not in a position to keep diaries or record books. Despite the lack of first-hand accounts representing the perspectives of the enslaved, we have an understanding from existing records that, despite risks of being harmed further or even being killed, those who were captured and forced onto ships did make attempts to take control of their lives by fighting back.

Terms:

Uprising: an act of resistance or rebellion; a revolt

Agency: taking action for oneself. An attempt at control over a situation

Sloop: a one-masted sailboat with a fore-and-aft mainsail and a jib

Merchant: a person or company involved in wholesale trade, especially one dealing with foreign countries or supplying merchandise to a particular trade

Brig: a two-masted, square-rigged ship with an additional gaff sail on the mainmast

Appeal: a serious or urgent request, typically one made to the public

Collection: a collection in a museum or library is a group of archives, manuscripts, or objects that belong together either by subject, time period, or type

Hearsay: information received from other people that one cannot adequately substantiate. Like a rumor

Questions:

From whose points of view are the above stories about uprisings told? Why?

In looking at the sources from this time period, what whose names are recorded? Whose names are missing?

What can the presence and absence of names tell us about what type of records were considered important to write and keep?

Think about the risks enslaved Africans took in fighting back on slave trading ships. Can you make any guesses, based on information in the essay, about why they may have thought the risks were worth it? What does the fact that they took this risk tell us about many enslaved Africans?

- 1Elizabeth Donnan. Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America. Vol. 1. (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1930.), p. 457-464

- 2Donnan, Vol. 2, p. 282

- 3Kenneth Scott. “George Scott, Slave Trader of Newport.” The American Neptune. Vol. 12, No. 3, July 1952. Peabody Museum of Science, Salem, Mass. p. 222-228

- 4MSS 17 Harris Family Papers, Box 2 Folder: 1730, Narrative of Slave Revolt on Ship off Africa

- 5Donnan, Vol. 3, p. 121

- 6MSS 828