African Free Union Society Meeting

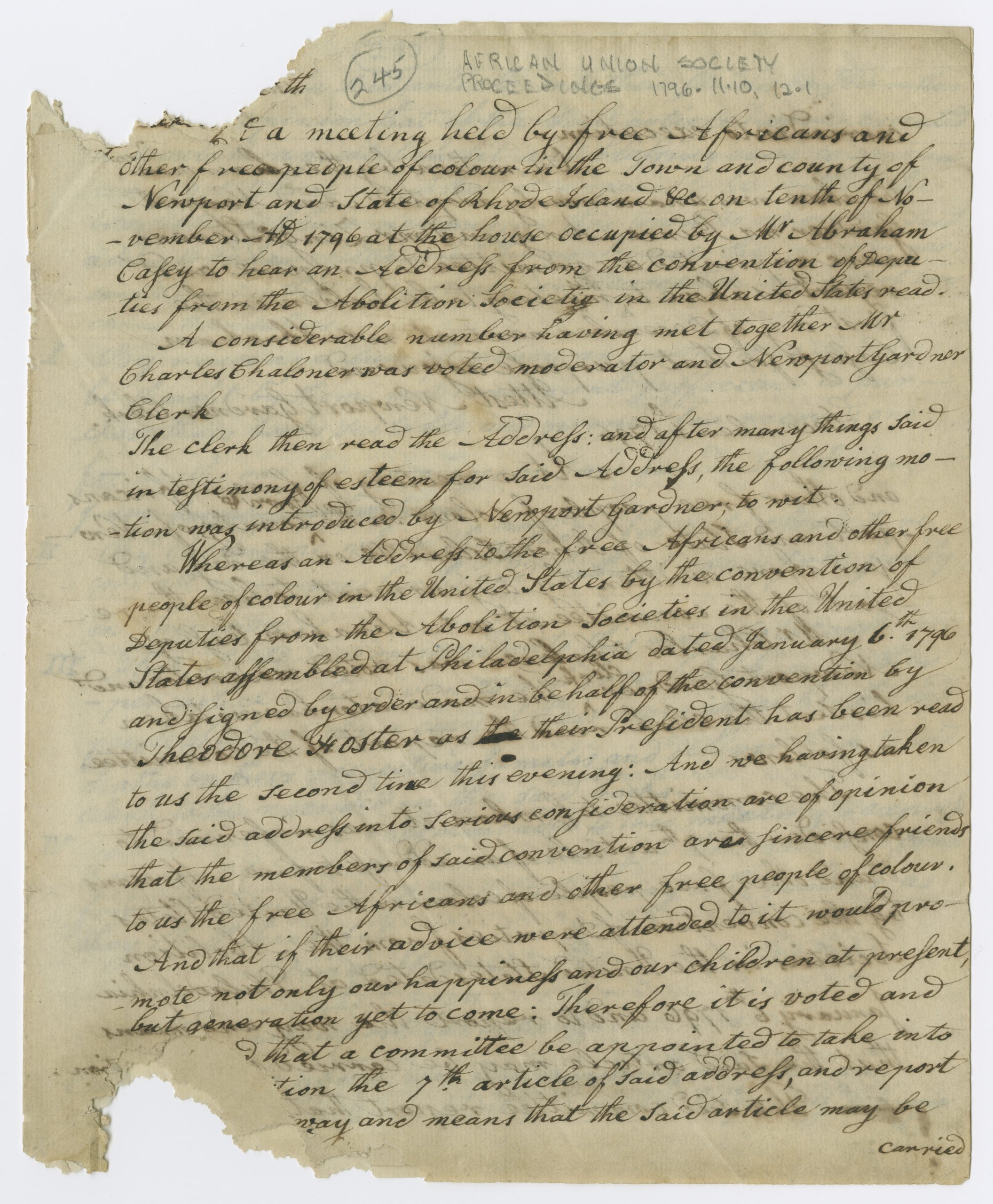

One page of proceedings of a “meeting held by free Africans and other free people of colour in the Town and county of Newport and state of Rhode Island on the tenth of November AD 1796 at the house occupied by Mr. Abraham Casey to hear an addendum from the convention of Deputies from the Abolition Society in the United States read….” Records identify a committee made up of Newport Gardner, Zingo Stevens, and Prince Amy. The goal of this society was to provide benefits that were otherwise denied to Black people because of racial discrimination, especially social and financial support. This included keeping the records of births and deaths, apprenticeship opportunities, and care for the sick, elderly, and widowed.

[Click here for the full document and transcription of the proceedings of the African Union Society]

Free Black Communities in Rhode Island

Essay by Rebecca Valentine, MLIS, Reference Librarian at the Rhode Island Historical Society

African and Black Americans have lived in Rhode Island since the mid-to-late seventeenth century—particularly after 1696, when Rhode Island entered the slave trade and the first documented slave ship, the Seaflower, brought enslaved Africans to Rhode Island.1Theresa Guzmán Stokes, “Rhode Island African Heritage & History Timeline: 17th through 19th Centuries,” 1696 Heritage Group, accessed July 24, 2020 [link]

As the population of Black people in the state grew, the existence of the slave trade and the institution of slavery in Rhode Island acted as a barrier to creating stable Black families and communities.2Christian McBurney, “Cato Pearce’s Memoir: A Rhode Island Slave Narrative,” Rhode Island History 67, no. 1 (2009) [link] While many of the enslaved people in Rhode Island were able to overcome those hardships and build stable families, the barriers increased when Rhode Island’s economy became more and more dependent on the slave trade. Sustaining Black communities in Rhode Island would require more than just a number of people living near each other—it required an organized effort.

The Rhode Island General Assembly passed laws to regulate society, and some of the laws passed were attempts to control the Black people living in Rhode Island. For example, a law that prohibited free Blacks from socializing with enslaved peoples was enacted in 1770.3Robert J. Cottrol, The Afro-Yankees: Providence’s Black Community in the Antebellum Era (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982), pg. 20 The punishments for breaking these laws were fines or indentured servitude. After the mid-1780s and the passing of the 1784 Gradual Emancipation Act, it was not uncommon for families to be made up of both free and enslaved peoples. This happened when one member of a family was able to purchase their own freedom but no one else’s, or when a slave master emancipated only one or two members of a family. Because of the mixture of free and enslaved people within the same household, Black Rhode Islanders risked a fine, or even their freedom, to keep their family together. The General Assembly also set curfews for people of color regardless of their free status.4Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York: New York University Press, 2018), pg. 39 Because many of the trades that were available to Black people required labor from sunup to sundown, curfews would limit time for socialization after a work day. The fines and risk of indenture as consequences of breaking these laws discouraged community building, making it so that those in power could continue to profit from the slave trade.

Despite those threats, the 1780s were a transitional period for Rhode Island. The American Revolution and the growing understanding of the horrors of the trans-Atlantic slave trade caused many White and Black Rhode Islanders to question the morality of keeping slaves. In 1777, when many states were unable to meet recruitment demands, Congress officially accepted the enlistment of enslaved men into the Continental Army.5Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York: New York University Press, 2018), pg. 70 Rhode Island created the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, which was largely made up of Black soldiers. By 1778, Colonel Greene offered Black recruits their freedom in return for service, and many of the members served until the regiment disbanded in 1783.

The moral contradiction that the war created—of fighting to end British oppression of the colonies while remaining oppressed in America—was not lost on the Black people of Rhode Island. In 1780, the Free African Union Society was founded in the home of Abraham Casey who lived on Levin Street in Newport, Rhode Island. The goal of this society was to provide benefits that were otherwise denied to Black people because of racial discrimination, especially social and financial support. This included keeping the records of births and deaths, apprenticeship opportunities, and care for the sick, elderly, and widowed.6Robert L. Harris, Jr., “Early Black Benevolent Societies: 1780-1830”, The Massachusetts Review, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Autumn, 1979), accessed July 21, 2020, pg. 609 [link] By 1789, this society was popular enough to include a Providence branch.7William H. Robinson, “The Proceedings of the Free African Union Society and the African Benevolent Society: Newport, Rhode Island 1780-1824” (1976), Faculty Publications, accessed March 24, 2020, pg. 19 [link]; and C.J. Martin, “Forever and Hereafter a Body Politic” The African Union Meeting House and Providence’s First Black Leaders,” Rhode Island History 77, No. 1 (2019), pg. 24

These two branches sometimes disagreed. In 1794 when the Providence branch of the Free African Union Society petitioned the Rhode Island General Assembly for help in sending their members to a colony in Sierra Leone, no one told the Newport Branch.8Robinson, “The Proceedings of the Free African Union Society and the African Benevolent Society”, pg. 43-44; and C.J. Martin, “Forever and Hereafter a Body Politic,” pg. 24 However, the need for social support was more important than differences of opinion, and the organization continued to operate until 1797. The Free African Union Society is an example of one of the first free Black communities coming together because the organization was founded by Black people for the support of Black people through social and monetary aid.

By 1800, public schools were not formally segregated in Rhode Island, but there was nothing in place to support integration either. This allowed the towns with the largest populations of African Americans, such as Providence, Newport, and Bristol, to have local laws that banned Black students from attending White schools. However, towns with very small populations did not explicitly ban Black students from White schools because there were too few students.9Clark-Pujara, Dark Work, pg. 122 Many Black people in Rhode Island viewed education as a way to move beyond the “ignorance and depression” that had been forced on them by the institution of slavery and racially oppressive laws.10Robinson, “The Proceedings of the Free African Union Society and the African Benevolent Society”, pg. 172 These unjust laws and unfair treatment inspired resistance in the free Black community, which took the form of constructive action.

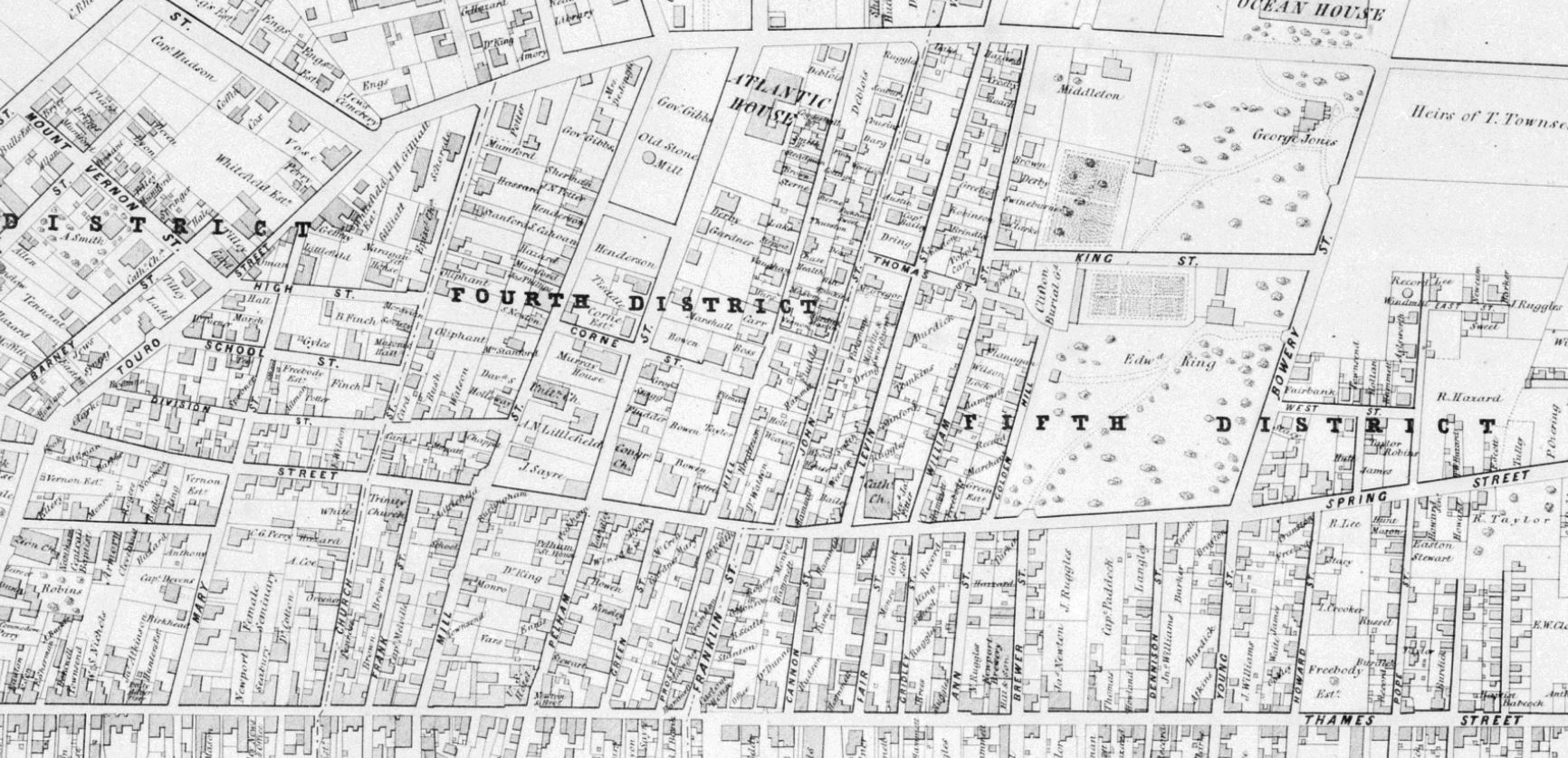

In 1807, the community founded the African Benevolent Society in Newport, Rhode Island. This new group had strong ties to the Free African Union Society. Many were members of both groups. While the new society would keep the goals of supporting the community by providing many of the same benefits, the founders of the African Benevolent Society also unanimously decided to open a school for their community.11Robinson, “The Proceedings of the Free African Union Society and the African Benevolent Society”, pg.153-4 Located on School Street in Newport, RI, the school was immediately successful. Although the official opening is recorded as March 1810, a letter to the president of the society noted that the school had taught 78 students by January 1809, and had placed an ad in the Newport Mercury in 1808 to encourage “the attendance of Africans” as students.12Robinson, “The Proceedings of the Free African Union Society and the African Benevolent Society”, pg. 158, 161 [link]; Keith Stokes, “A Place for All,” Newport Daily News (Newport), 2014, accessed July 27, 2020 [link] While the school did have some trouble finding and keeping teachers, a few of the society’s founders acted as instructors during the first few years of operation.13Clark-Pujara, Dark Work, pg. 123 This group helped grow a free Black community because the founders saw the lack of education as adding to their overall oppression, and worked together to fill that void.

In 1800, Rhode Island’s free Black population began to shift where they were located. During the Revolutionary war, Newport was occupied by the British because the port offered easier access to other New England Colonies and New York. British forces took complete control of the city and its shipping businesses. No one could leave or return without written permission, and all boats had to be registered with British authority. If the British thought someone was secretly a rebel or helping the rebels, they would be punished.14Fred Zilian, “British and Hessian Forces Occupy Newport and Aquidneck Island in 1776,” Smallstatebighistory.com, April 7, 2017, accessed July 30, 2020 [link] The rules during this occupation were so strict that many people went out of business entirely, and the city and its people struggled to recover economically after the end of the war. This enabled Providence to expand its trade and commerce, which attracted more of the sailors who worked in the shipping industries, many of whom were Black. By 1819, the free Black population in Providence increased enough to support their own community groups.15W. Jeffrey Bolster, “To Feel Like A Man: Black Seamen in the Northern States,” The Journal of American History, Vol. 76, No. 4 (Mar., 1990), pp. 1173-1199; W. Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, (1997); Jeffrey Howe, “Black and Indian Sailors Born in Rhode Island: Bristol Custom House Protection Papers,” Rhode Island Roots (June 2005): 91-98; Jeffrey Howe, “Black and Indian Sailors Born in Rhode Island: Providence Customs House Records, Part I: A-C,” Rhode Island Roots (September 2006): 156-163; Jeffrey Howe, “Black and Indian Sailors Born in Rhode Island: Providence Customs House Records, Part II: D-J,” Rhode Island Roots (December 2006): 197-207; Jeffrey Howe, “Black and Indian Sailors Born in Rhode Island: Providence Customs House Records, Part III, K-Y,” Rhode Island Roots (March 2007), p. 97; Jeffrey Howe, “Black and Indian Sailors from Rhode Island: Bristol Crew Lists,” Rhode Island Roots (September 2005): 143-55; Jeffrey Howe, “Black and Indian Sailors Born in Rhode Island: New London, Connecticut, Protectorate Records,” Rhode Island Roots (December 2005): 196-200

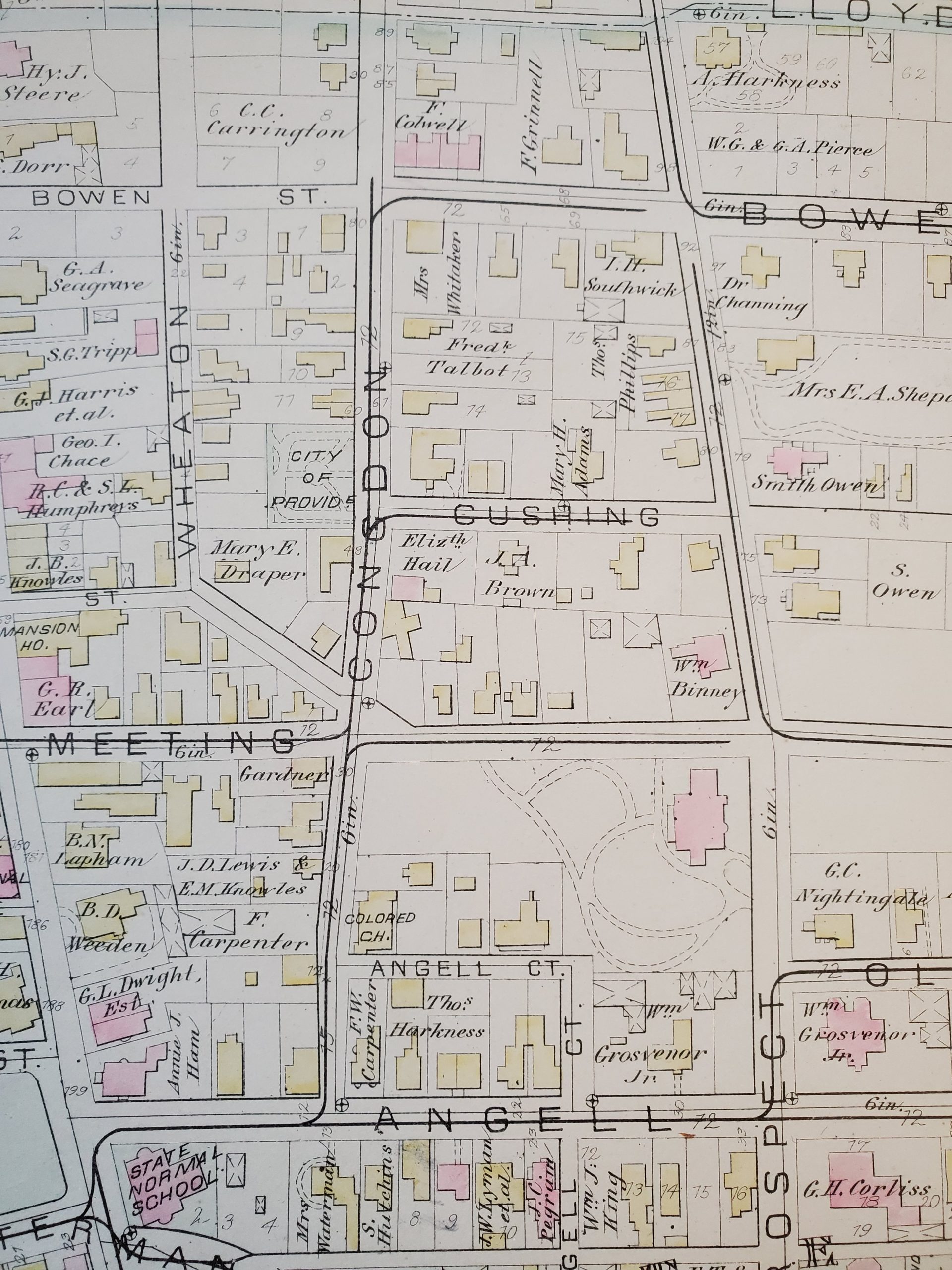

The growing Providence community was especially interested in creating spaces of their own. While Black Rhode Islanders were permitted to worship and attend church, they were required to sit in “pigeonholes.” These were segregated pews high up in the balcony area and out of sight from White churchgoers.16William J. Brown, The Life of William J. Brown (Providence, RI: Angell and Printers, 1883), pg. 46 This unfairness prompted the creation of a place of worship specifically meant for Black people. After three years of planning, building, and a gift of land on the corner of Congdon and Meeting Streets in Providence, RI, the African Union Meeting House and School was dedicated in 1822, though the building had already been in use as a school and church before that.17Brown, The Life of William J. Brown, pg. 83

The African Union Meeting House served as a church and was originally nondenominational, meaning that it was open to all forms of worship. The building also housed a school in the basement for the education of Black children.18Brown, The Life of William J. Brown, pg. 48; and C.J. Martin, “Forever and Hereafter a Body Politic,” pg. 23 The African Union Meeting House and School continued to operate out of the same building on the corner of Congdon and Meeting Streets until 1869, When the organization was gifted a new lot of land on the corner of Congdon Street and Angell Court. The organization’s name was changed by an act of state legislation to the Congdon Street Baptist Church. Congdon Street Baptist Church still operates today.19“History,” Congdon Street Baptist Church, accessed July 24, 2020 [link] This group is another example of the creation of a free Black community in Rhode Island, whose members could learn and gather together without fear of oppression or reprisal.

Community development flourishes when large groups of people cooperate to live and work near each other as well as when people with similar opinions and experiences are close to one another. The growth and expansion of free Black communities in Rhode Island involved these factors, as well as a desire to support all members of their community. Free Black communities supported one another through social and financial aid, creating opportunities for education, building, and investing in their own spaces where they could exist relatively free from prejudice and unfair treatment. These communities formed because there was a need for support, and people were willing to help one another.20Harris, Jr., “Early Black Benevolent Societies”, pg. 611; and Robert J. Cottrol, The Afro-Yankees, pg. 8 These communities could not combat all injustices caused by the systemic oppression that Black people faced daily, but their efforts lessened the burden and strengthened the ability to resist those injustices.

Terms:

Rhode Island General Assembly: the state-level governing body of Rhode Island. It is composed of a House of Representatives and a Senate

Prohibit: to formally forbid something through authority, like laws or rules

Indentured servitude: someone who is bound by a signed or forced contract (indenture) to work without pay for a period of time. people who entered into indentured servitude usually entered into the contract for a specific benefit (such as transportation to a new place), or to meet a legal responsibility, such as debt bondage

Gradual Emancipation Act of 1784: according to this act, children born to enslaved people would not remain enslaved and masters could manumit healthy enslaved people between the ages of 21 and 40 without assuming financial responsibility. It was meant to slowly phase out slavery

Curfews: regulations requiring people to remain indoors between specified hours, typically at night

Morality: principles concerning the distinction between right and wrong or good and bad behavior

Continental Army: established by a resolution of the Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in their revolt against the rule of Great Britain. The Continental Army was supplemented by local militias and volunteer troops that remained under the control of the individual states or were otherwise independent

Colonel Christopher Greene: he served in the Rhode Island legislature from 1772-1774. He became a lieutenant in the Kentish Guards of the Revolutionary Army in 1774. He was promoted to major in 1775 by George Washington. In 1776, he was promoted to colonel, and was placed in charge of Fort Mercer, N.J., defending during the Battle of Red Bank on October 22, 1777. After returning to Rhode Island, Col. Greene helped assemble the 1st Rhode Island regiment, a regiment of free African Americans and enslaved men who were freed to serve in the army. Col. Greene and his troops participated in the Battle of Rhode Island, which began on August 29, 1778. Along with several members of his regiment, he was killed by Loyalists at the Battle of Pine’s Bridge on March 14, 1781.

Abraham Casey: a property holder and member of a small but influential Black middle class, he owned a two-story home on Levin Street

Levin Street: a street in Newport, Rhode Island that was widened in the 1960s and renamed Memorial Boulevard

Apprenticeship: the position of an apprentice, a person who is learning a trade from a skilled employer, having agreed to work for a fixed period at low wages in exchange for training

Monetary: relating to money or currency

Segregated: set apart from each other; isolated or divided

Integration: the action or process of bringing people or groups with particular characteristics or needs into equal participation in a social group or institution

Ignorance: the lack of knowledge or information

Depression: the action of lowering something or pressing something down

Unanimously: without opposition; with the agreement of all people involved

Oppression: prolonged cruel or unjust treatment or control

Occupied: control and possession of hostile territory that enables an invading nation to establish military government against an enemy or martial law against rebels or insurrectionists in its own territory.

Commerce: the activity of buying and selling, especially on a large scale

Nondenominational: open or acceptable to people of any Christian denomination

Systemic oppression: oppression that occurs at the institutional level, such as in government policymaking or within educational institutions

Questions:

Why would the Rhode Island General Assembly want to control the lives of its free Black residents?

Why do you think the African Benevolent Society chose to open its own school for Black children rather than advocating for the integration of Black children into White schools?

After reading this essay and learning about the actions taken by free Black communities in Rhode Island, how would you define “community.” What do communities provide, who is a part of them, and how do they function?

- 1Theresa Guzmán Stokes, “Rhode Island African Heritage & History Timeline: 17th through 19th Centuries,” 1696 Heritage Group, accessed July 24, 2020 [link]

- 2Christian McBurney, “Cato Pearce’s Memoir: A Rhode Island Slave Narrative,” Rhode Island History 67, no. 1 (2009) [link]

- 3Robert J. Cottrol, The Afro-Yankees: Providence’s Black Community in the Antebellum Era (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982), pg. 20

- 4Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York: New York University Press, 2018), pg. 39

- 5Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York: New York University Press, 2018), pg. 70

- 6Robert L. Harris, Jr., “Early Black Benevolent Societies: 1780-1830”, The Massachusetts Review, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Autumn, 1979), accessed July 21, 2020, pg. 609 [link]

- 7William H. Robinson, “The Proceedings of the Free African Union Society and the African Benevolent Society: Newport, Rhode Island 1780-1824” (1976), Faculty Publications, accessed March 24, 2020, pg. 19 [link]; and C.J. Martin, “Forever and Hereafter a Body Politic” The African Union Meeting House and Providence’s First Black Leaders,” Rhode Island History 77, No. 1 (2019), pg. 24

- 8Robinson, “The Proceedings of the Free African Union Society and the African Benevolent Society”, pg. 43-44; and C.J. Martin, “Forever and Hereafter a Body Politic,” pg. 24

- 9Clark-Pujara, Dark Work, pg. 122

- 10Robinson, “The Proceedings of the Free African Union Society and the African Benevolent Society”, pg. 172

- 11Robinson, “The Proceedings of the Free African Union Society and the African Benevolent Society”, pg.153-4

- 12

- 13Clark-Pujara, Dark Work, pg. 123

- 14Fred Zilian, “British and Hessian Forces Occupy Newport and Aquidneck Island in 1776,” Smallstatebighistory.com, April 7, 2017, accessed July 30, 2020 [link]

- 15W. Jeffrey Bolster, “To Feel Like A Man: Black Seamen in the Northern States,” The Journal of American History, Vol. 76, No. 4 (Mar., 1990), pp. 1173-1199; W. Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, (1997); Jeffrey Howe, “Black and Indian Sailors Born in Rhode Island: Bristol Custom House Protection Papers,” Rhode Island Roots (June 2005): 91-98; Jeffrey Howe, “Black and Indian Sailors Born in Rhode Island: Providence Customs House Records, Part I: A-C,” Rhode Island Roots (September 2006): 156-163; Jeffrey Howe, “Black and Indian Sailors Born in Rhode Island: Providence Customs House Records, Part II: D-J,” Rhode Island Roots (December 2006): 197-207; Jeffrey Howe, “Black and Indian Sailors Born in Rhode Island: Providence Customs House Records, Part III, K-Y,” Rhode Island Roots (March 2007), p. 97; Jeffrey Howe, “Black and Indian Sailors from Rhode Island: Bristol Crew Lists,” Rhode Island Roots (September 2005): 143-55; Jeffrey Howe, “Black and Indian Sailors Born in Rhode Island: New London, Connecticut, Protectorate Records,” Rhode Island Roots (December 2005): 196-200

- 16William J. Brown, The Life of William J. Brown (Providence, RI: Angell and Printers, 1883), pg. 46

- 17Brown, The Life of William J. Brown, pg. 83

- 18Brown, The Life of William J. Brown, pg. 48; and C.J. Martin, “Forever and Hereafter a Body Politic,” pg. 23

- 19“History,” Congdon Street Baptist Church, accessed July 24, 2020 [link]

- 20Harris, Jr., “Early Black Benevolent Societies”, pg. 611; and Robert J. Cottrol, The Afro-Yankees, pg. 8