Rhode Island in the American Revolution

Essay by Robert A. Geake, author and public historian

Rhode Islanders have always prided themselves on their independent spirit, from the time of their early resistance in the 17th century to Puritan authority in neighboring colonies to the beginnings of the conflict with Great Britain, when its citizens were at the forefront of declaring their independence. Many Rhode Islanders who desired to free the colonies from British rule were sons and daughters of the veterans of the resistance against the Navigation Acts that, for years, had sought to control and tax the goods brought into the colony. Many had come of age during the rebellions against the Stamp Act in 1765 and the attacks upon British ships docked in Newport that same year.1Florence Parker Simister, The Fire’s Center: Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era 1760-1792, Providence, Rhode Island Historical Society 1979, 13-16

Resistance against these Acts of Parliament included that of Stephen Hopkins, the elected Governor of Rhode Island, who risked being arrested for treason due to his inflammatory pamphlets against the Crown’s implementation and enforcement of these regulations.2Stephen Hopkins The Rights of the Colonies Reexamined Providence, William Goddard 1765

Molasses was the chief import of the colony, and so it was the lever that the British could use to generate the most revenue and control the many rum distilleries Rhode Island operated around its ports. The use of molasses in making rum was the key ingredient in the triangle trade economy of exchanging rum for enslaved people on the African coast, selling those enslaved people for money and cane sugar in the West Indies, and then procuring more molasses to be brought back to Newport and Providence where the process would begin again.

Spinning Wheel

Read about the women's homespun movement here

When British revenue schooners stepped up their patrolling of Narragansett Bay in the spring of 1772, Rhode Islanders led the resistance. Such schooners began to stop and search any and all boats entering the harbor at Aquidneck Island or heading up the bay to Warwick and Providence. In June 1772, the Hannah, a merchant ship owned by Providence merchant John Brown, lured the H.M.S. Gaspee to the sandbar at Namquid Point, where the British vessel ran aground, giving the dockworkers in Providence the opportunity to lay siege to the schooner and ultimately, burn the ship to the waterline.3Rhode Island Colonial Records 1770-1776 Vol. 7, 55-189

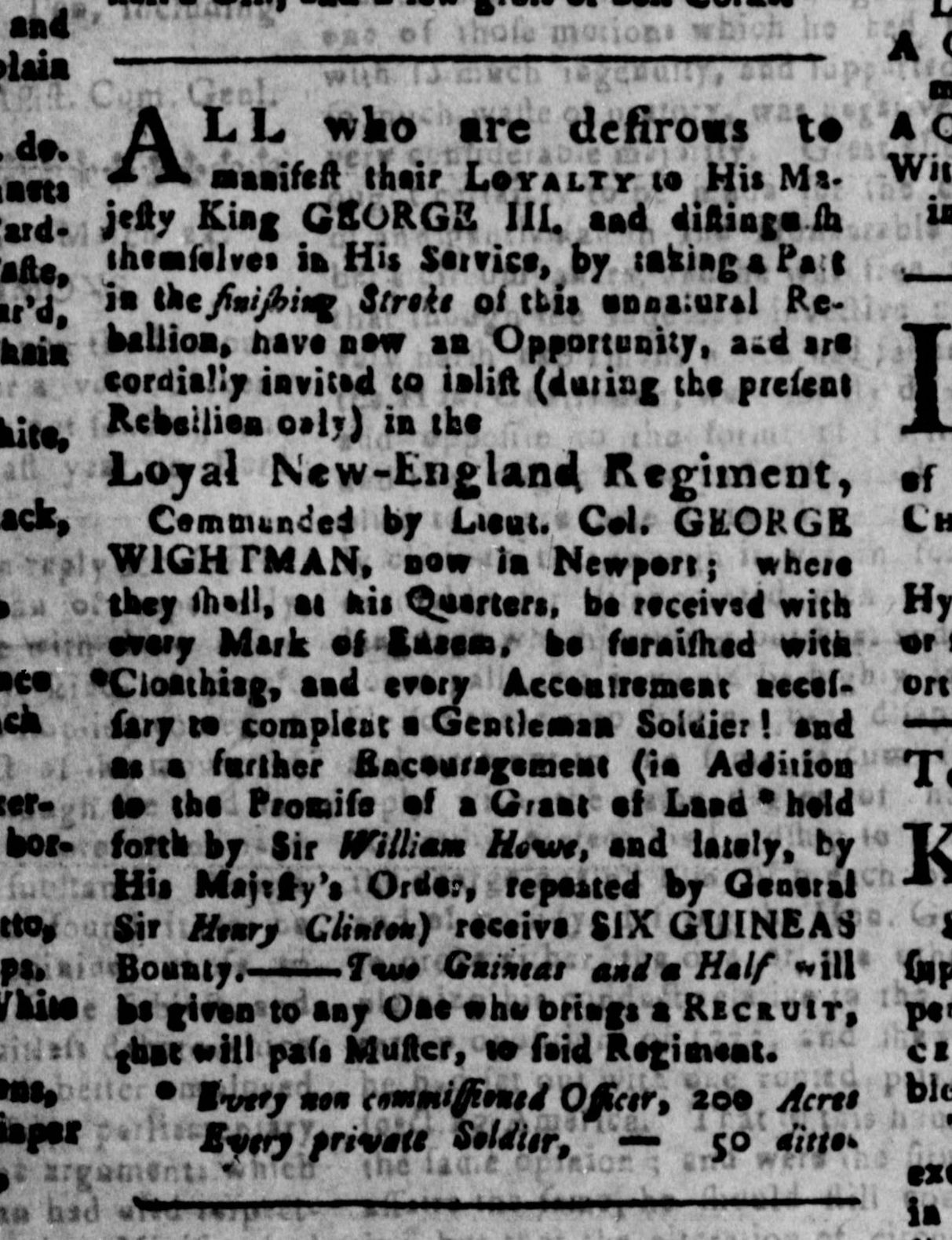

Newport Gazette – Loyalist Newspaper

Read about loyalists during the Revolutionary War here

While it was those merchants who clamored for independence through hired freelance writers penning columns and letters in local newspapers such as the Providence Gazette, the idea resonated with nearly all Rhode Islanders whose desire, as would eventually be phrased in the Declaration of Independence, was the right to the pursuit of happiness. In terms we would understand today, “pursuing happiness” simply meant the opportunity to earn a living or as much work and income as you could achieve without being burdened by tariffs and taxes imposed upon the colonies by the British government. Such burdens imposed by the British meant that it was not only the merchants who owned the shipping vessels who suffered the loss of income but also the farmers whose goods were shipped on those vessels, the proprietors of stores and warehouses who sold the goods shipped at a profit, as well as the sail makers, rope makers, caulkers, coopers, carpenters, mariners and dockworkers upon whom merchant shipping depended. Most importantly, stricter enforcement of trade regulations and the prospect of added taxes affected those young men of the colony who were just getting their start in commerce or those myriad businesses associated with such commerce. It is important to remember that the average age of the soldiers who would occupy General Washington’s army was between twenty and twenty-five years.4Based upon a study at Valley Forge in 1777. See The Young and the Restless… [link]

For these and other reasons, Rhode Islanders responded to the call for rebellion. In the wake of the Gaspee affair, armed resistance began to grow throughout the colony. The Assembly set the loyalist leaning Governor’s wishes aside, and formed an Army of Observation, as well as a Committee of Safety to correspond with like committees in the neighboring colonies.5Rhode Island Colonial Records 1770-1776 Vol. 7, 262-263

Preparedness began in earnest in 1774. Communities began to form independent militias such as the Scituate Hunters, the Kentish Guard, and other units. The Kentish Guard would contribute more officers of importance to the Continental Army than any other company in the colonies. In Providence, the county militias were formed into one Cadet Company, and a commander was appointed. Young men joined the militia in Cumberland, Newport, North Kingstown, North Providence, and Pawtuxet as well.

On February 18, 1775, the Providence Gazette noted that

“Not a day passes, Sundays excepted, but some of the companies are under arms; so well convinced are the people, that the complexion of the times renders a knowledge of the military art indispensably necessary”.

This meant that nearly every able-bodied man (and a number of boys) in Rhode Island were mustering, marching, and practicing military at every opportunity. On the first Monday of April 1775, a general muster of the militia in the colony brought out some two thousand men as well as a troop of light horse infantry.

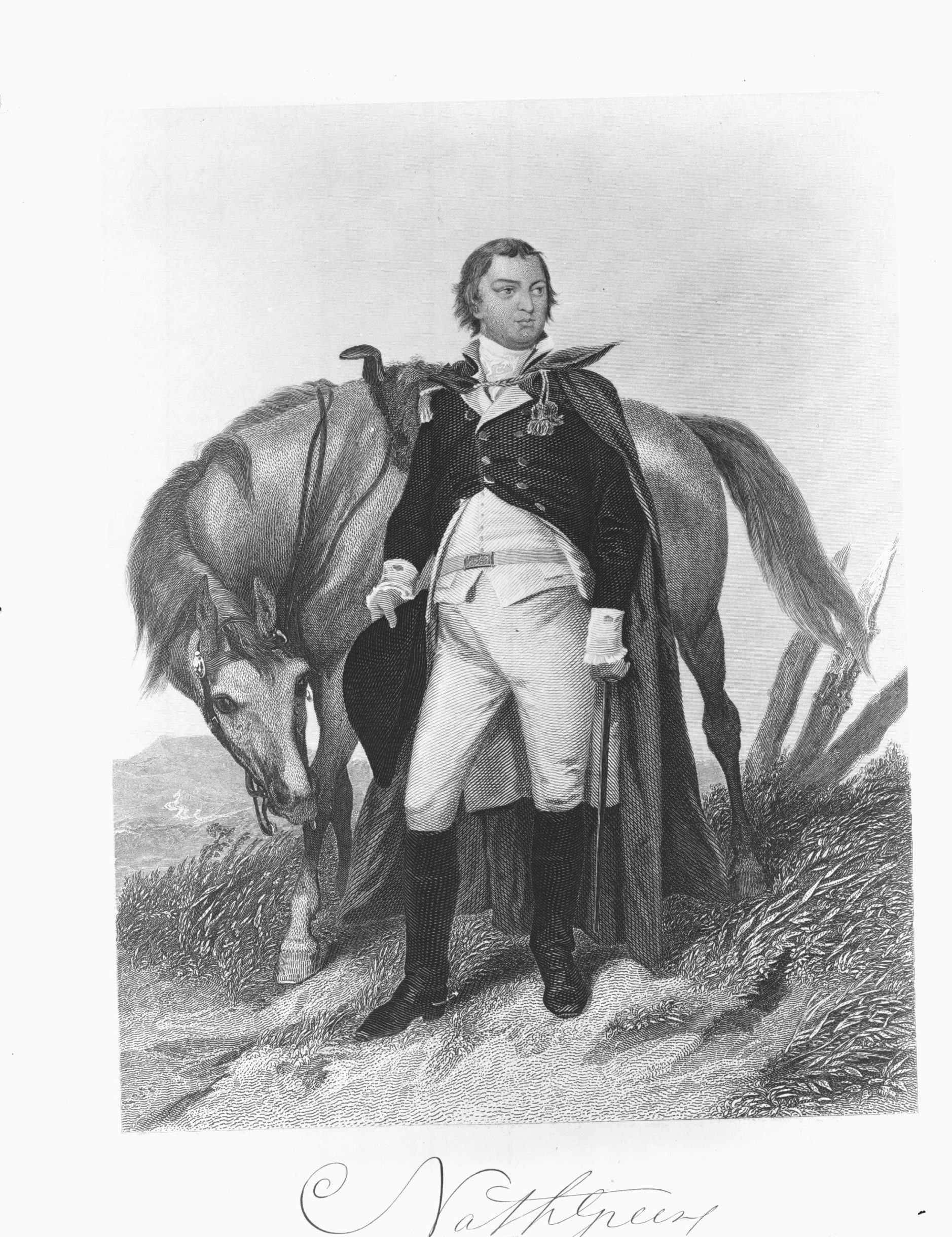

Engraving of Nathanael Greene

Learn about Nathanael Greene here

When word came of the confrontation in Lexington and Concord on April 19th, the Rhode Island militia prepared to join the fight. They decided against it when they learned the British had retreated to Boston. In late May, one thousand Rhode Island troops joined the patriot army during the siege of Boston. Augustus Mumford died from a cannon shot during that siege and was the first Rhode Islander killed during the Revolution. Rhode Island troops were encamped at Jamaica Plain and Prospect Hill.6William G. McLoughlin. Rhode Island: A History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. 1986: 93; Florence Parker Simister The Fire’s Center 82

A great many of the men who marched on the alarm would be conscripted into the Continental Army, and eagerly volunteer for General Benedict Arnold’s ill-fated expedition to Quebec in the fall of that year.7For more information, see History.com article [link] Many would be taken prisoner when the siege of that city failed, some serving two to three years in the infamous “Salt Factory” prison in New York City.

Preparations continued for the defense of Rhode Island. In July 1775, it was decided to have troops construct fortifications at Fox Point and build breastworks at Sassafras and Field’s Points. In addition, a number of scows were sunk near the entrance to the Providence River, and a chain and boom stretched across the mouth of the harbor. Beacons were constructed at the head of the Providence River and as far inland as Chopmist Hill in Scituate. Six months later the General Assembly of Rhode Island declared that “a number of men, not exceeding fifty, be stationed at Warwick Neck, including the Artillery Company in Warwick; the remainder to be minutemen”. According to Edward Field, “a substantial work…was erected” and in addition to the fort, “a system of entrenchments was laid out along the northerly side of the old road leading from Apponaug to Old Warwick”.8Edward Field Revolutionary Defenses in Rhode Island Providence, Preston & Rounds 1896, 56-59, 84

That same session saw the formation of the United Train of Artillery and a brigade of light infantry. The Artillery Company’s six cannons were to be hauled to Dorchester Heights and utilized in the Siege of Boston.

In October 1775, the Congress of the Confederation, the congress established by the colonies before winning independence, ordered two vessels to be outfitted as part of the Continental Navy. One vessel named the Katy was one of those purchased, renamed the Providence, and shortly after sailed with one hundred men for Philadelphia. She became one of five ships in the fledgling navy. Congress soon ordered thirteen more vessels to be built, and in December, Esek Hopkins, brother of former governor Stephen Hopkins, was appointed Commander in Chief of the fleet.

More appealing than sailing on a navy vessel was the opportunity to serve on one of the licensed privateering ships that sailed from Providence. Their crews earned a share of prizes captured, and for many men of color, life at sea came with more equality than any opportunity offered on land. These ships played an important role in disrupting supplies from coming into Boston and New York, as well as capturing needed provisions and ships for the American cause.9Alexander Boyd Hawes. Off Soundings: Aspects of the Maritime History of Rhode Island. Bethesda: Posterity Press, Inc., 1999

On May 4, 1776, the General Assembly met at what is now the Old State House in Providence and voted to renounce allegiance to King George III. Two months later, the Continental Congress’s Declaration of Independence would be read around Rhode Island to cheering crowds.10Simister, The Fire’s Center 102-105

All able-bodied men were enlisted to serve in the Continental Army and marched to Boston to be sworn in, then on to New York. Other enlistees who had not passed muster or were deemed by the Army not fit to enlist but could serve in local militia remained in Rhode Island until they were called on to support an army campaign.11Samuel Smith, Memoirs of Samuel Smith A Soldier of the Revolution 1776-1786 New York, Bushnel 1860, 8-9

Coastal communities in Rhode Island were subject to raiding parties of British troops long before the taking of Newport in December of 1776. Rhode Island troops led by Colonel William Richmond and Colonel James Lippitt contributed to victories at Trenton and Princeton. Their home communities were hosts to men from neighboring town militias, as well as men from Massachusetts and Connecticut.

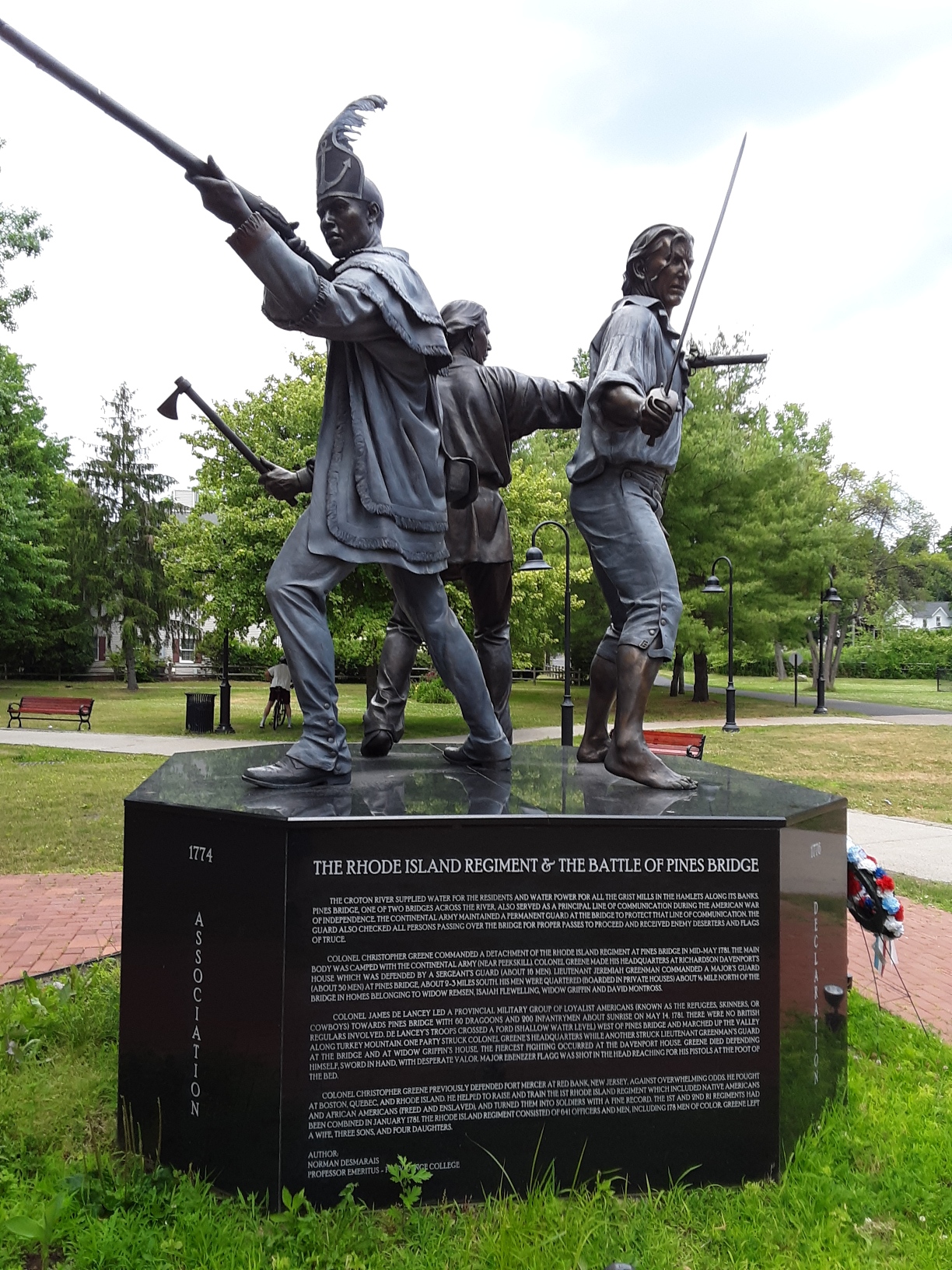

The Battle of Pines Bridge Monument

Learn about the 1st Rhode Island regiment here

Local churches would attend to these men, often sending visitors to sing hymns and hold informal prayer meetings at encampments. Women gathered clothing and blankets for the soldiers, and local merchants sold what they could when troops came seeking provisions. The lack of bread and meat was a substantial hardship for soldiers and civilians alike during the war.12Robert A. Geake Fired A Gun at the Rising of the Sun: The Diary of Noah Robinson of Attleborough, Massachusetts during the Revolutionary War Providence, RI Footprints Press 2018 pp. 25, 45, 115. See also Benjamin Cowell, Spirit of ’76 in Rhode Island, Boston, 1850 p. 163

As the war continued, the shortage of available troops began to plague the Army. During the winter of 1777, General James Mitchell Varnum conceived of a plan to assemble a regiment of enslaved Black men to bolster the number of soldiers required from Rhode Island. As passed by the General Assembly in February 1778, any enslaved Black or Indigenous person could enlist and, after three years of service, be discharged as a freeman. Recruitment fell short of a full regiment, so the remainder included those from Col. Christopher Greene’s regiment, which included free Blacks and Indigenous men, in addition to men of European descent.

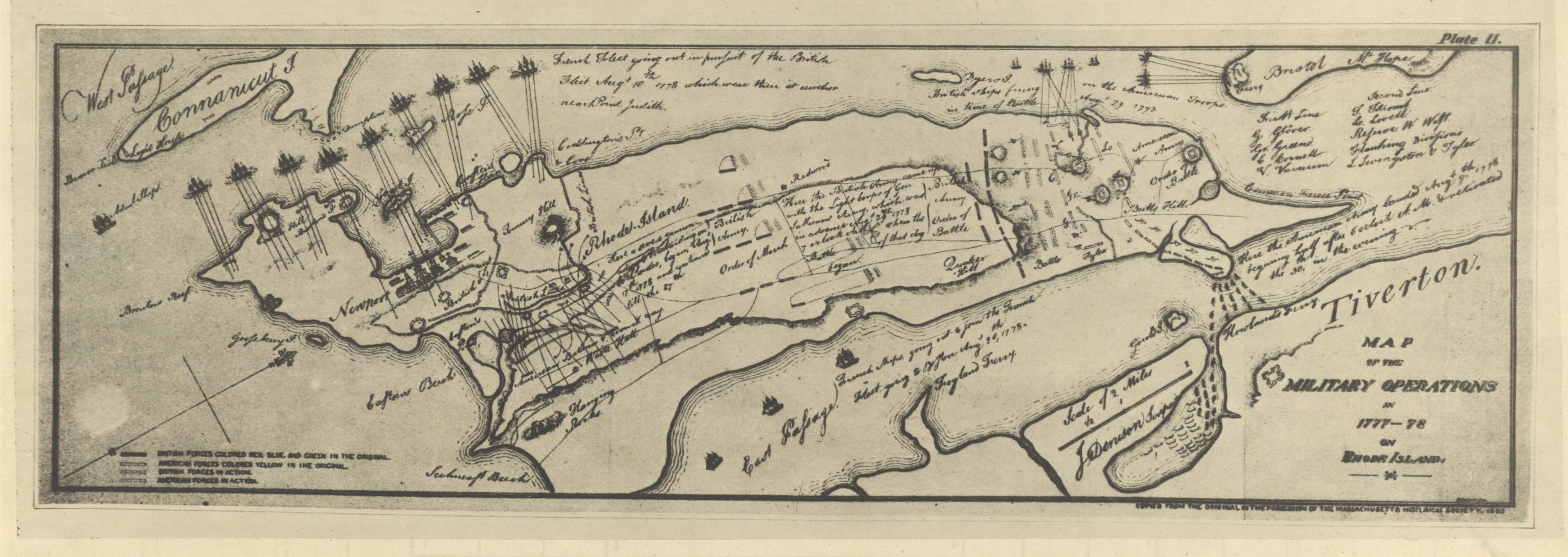

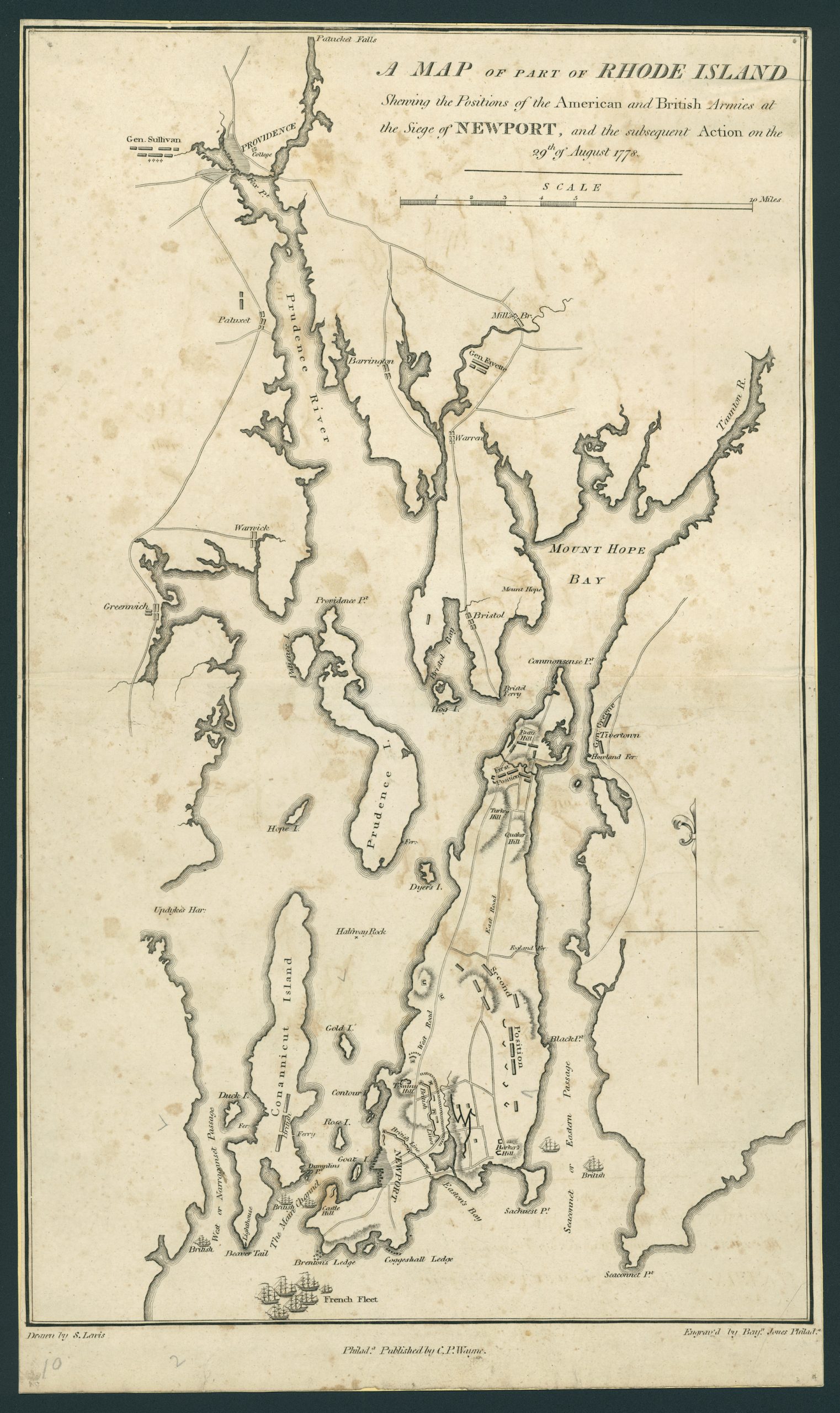

Map of the Siege of Newport

Learn about the change in power from Newport to Providence following the war

Greene was named commander, and the regiment trained for six months at East Greenwich. They faced their first battle on Aquidneck Island during the long-anticipated effort to take back Newport from the British. An earlier attempt had been abandoned, but by the summer of 1778, troops had received the call to gather at Rhode Island.13Greenman, Jeremiah Diary of a Common Soldier in the American Revolution 1775-1783 DeKalb, Northern Illinois University Press 1978, 126

The invasion to expel the British was hampered by poor preparation and miscommunication between American Generals and their new allies from France, who had sent a fleet to aid in the attack. A contingent force had been landed on the island but stranded from support by a heavy gale that blew for two days through the encampments and whipped the sea into a fury, damaging sails and rigging on the French vessels and causing their retreat to Boston.

The Rhode Island troops who had taken control of an abandoned British redoubt were evacuated during the battle of August 29th. The 1st Rhode Island regiment was positioned in a valley between Durfee and Butt Hill, the last defensive position of the Army, and repelled assaults from Hessians three times during the afternoon; protecting the troops being ferried across to Tiverton.14Christian M. McBurney The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation of the Revolutionary War Yadley, Westholme Publishing 2011, 170-203

The British would eventually depart Newport in October 1779, and the French would assist in protecting the island for the remainder of the war. While Rhode Island citizens could breathe a sigh of relief, the young men of Rhode Island were still engaged in the cause of liberty. The 1st Rhode Island regiment suffered major losses in May 1781 while encamped in New York but went on to contribute support for troops at Yorktown, Virginia. The 2nd Rhode Island regiment took part in battles at Monmouth, New Jersey and Springfield, Connecticut between 1778-1780. The 1st and 2nd regiments were consolidated in January 1781 as an integrated unit of the Continental Line until they were disbanded at Saratoga, New York in January 1783.

The young men who risked all for revolution returned to a Rhode Island that quickly became embroiled in the battle over paying the debts of war, and as a result, many waited years for their promised pay and pensions. Still, they proudly displayed their uniforms and weapons at parades and ceremonies in the years that followed and bore the pride of knowing that when they passed, the newspapers and monuments to their memory would forever identify them as “a soldier of the revolution.”

Terms:

Schooners – sailing ships with front and rear sails on two or more masts

Loyalist – a person loyal to the British government as opposed to being a patriot of the idea of a new, separate country

Mustering – enlisting into military service

Scow – flat-bottomed sailboat

Privateering Ship – a ship owned privately but commissioned by a government to attack and raid others in times of war

Hessians – German troops fighting on the side of the British

- 1Florence Parker Simister, The Fire’s Center: Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era 1760-1792, Providence, Rhode Island Historical Society 1979, 13-16

- 2Stephen Hopkins The Rights of the Colonies Reexamined Providence, William Goddard 1765

- 3Rhode Island Colonial Records 1770-1776 Vol. 7, 55-189

- 4Based upon a study at Valley Forge in 1777. See The Young and the Restless… [link]

- 5Rhode Island Colonial Records 1770-1776 Vol. 7, 262-263

- 6William G. McLoughlin. Rhode Island: A History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. 1986: 93; Florence Parker Simister The Fire’s Center 82

- 7For more information, see History.com article [link]

- 8Edward Field Revolutionary Defenses in Rhode Island Providence, Preston & Rounds 1896, 56-59, 84

- 9Alexander Boyd Hawes. Off Soundings: Aspects of the Maritime History of Rhode Island. Bethesda: Posterity Press, Inc., 1999

- 10Simister, The Fire’s Center 102-105

- 11Samuel Smith, Memoirs of Samuel Smith A Soldier of the Revolution 1776-1786 New York, Bushnel 1860, 8-9

- 12Robert A. Geake Fired A Gun at the Rising of the Sun: The Diary of Noah Robinson of Attleborough, Massachusetts during the Revolutionary War Providence, RI Footprints Press 2018 pp. 25, 45, 115. See also Benjamin Cowell, Spirit of ’76 in Rhode Island, Boston, 1850 p. 163

- 13Greenman, Jeremiah Diary of a Common Soldier in the American Revolution 1775-1783 DeKalb, Northern Illinois University Press 1978, 126

- 14Christian M. McBurney The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation of the Revolutionary War Yadley, Westholme Publishing 2011, 170-203