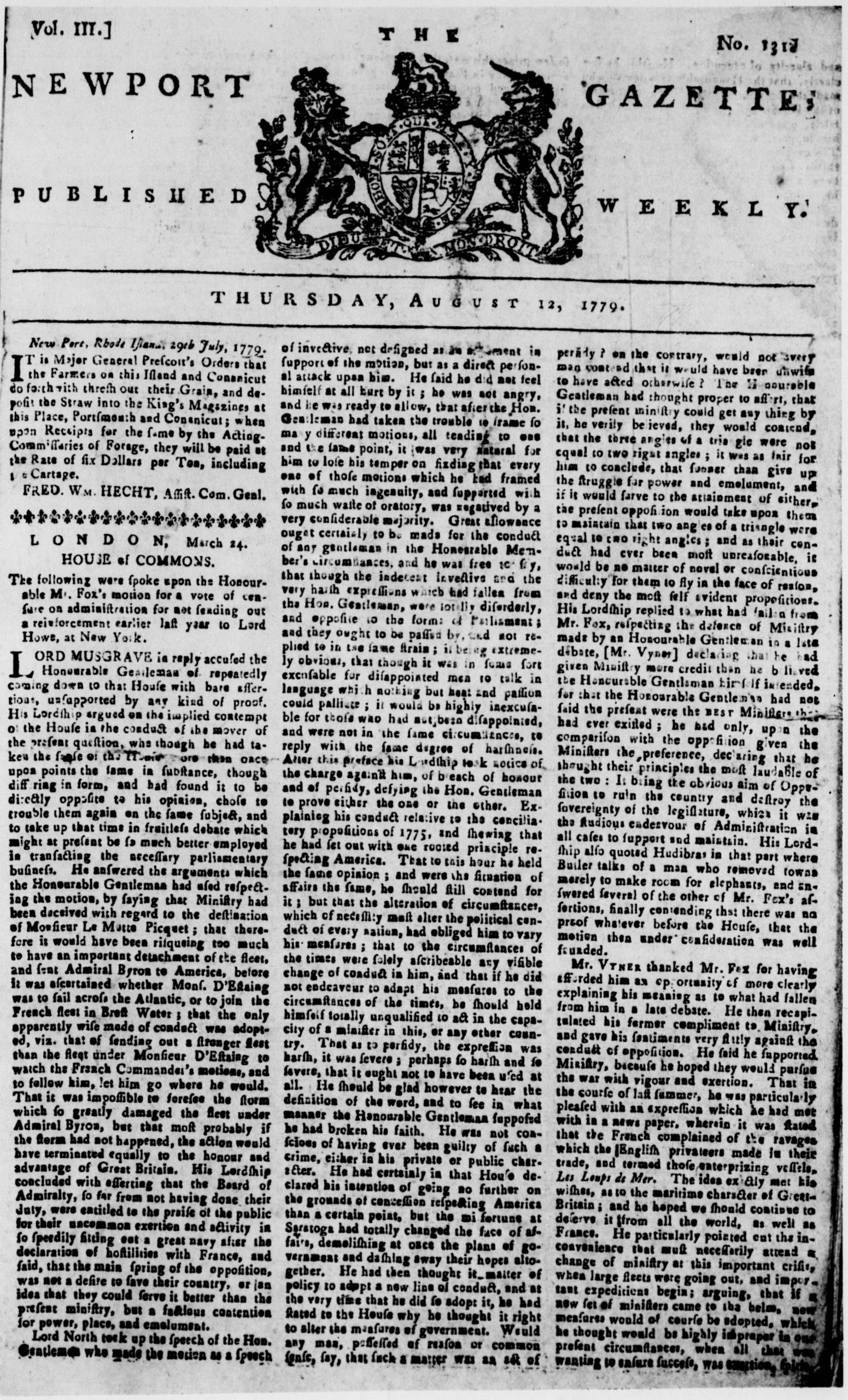

Newport Gazette – Loyalist Newspaper

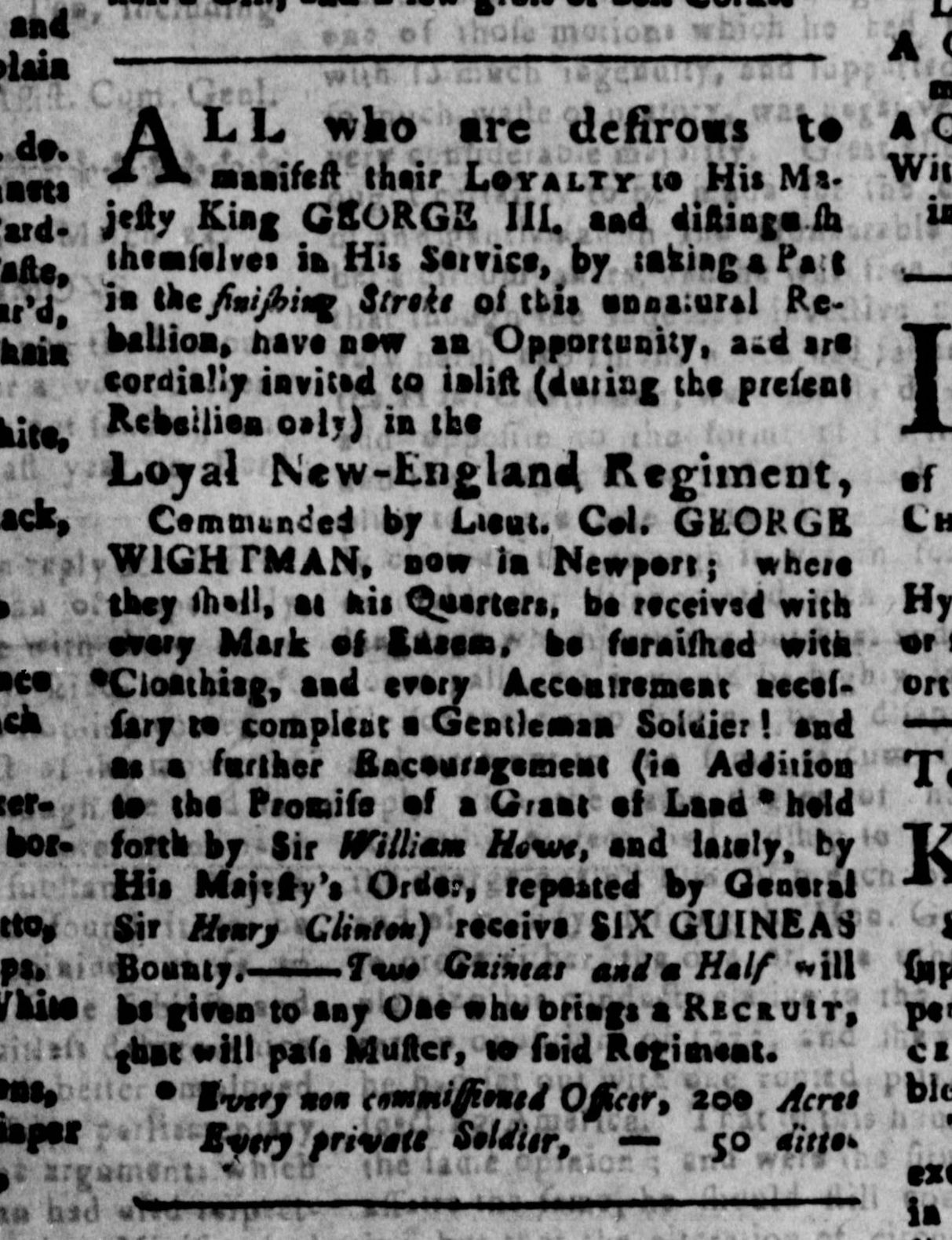

This Tory newspaper ran weekly and was established on January 16, 1777, by John A. Howe of New York while the British occupied Newport during the American Revolutionary War. It was printed on the hand press just previously used to print the Newport Mercury.

The pro-revolution Newport Mercury was suspended with the issue of Dec. 2, 1776 (no. 954 instead of 955), and as the British forces advanced on Newport, printer Solomon Southwick buried his press and types (see Newport Mercury, June 12, 1858) and fled to Rehoboth, Mass. Six days later, on Dec. 8, 1776, the British occupied Newport. The press was discovered and used to print pro-British news in the Newport Gazette.

The last known issue is that of Oct. 6, 1779, vol. 3, no. 139, which, according to Clarence S. Brigham, “must have been nearly the last number, as the British evacuated Newport, Oct. 25,1779. “

Loyalism in Rhode Island

Essay by Sarah Heavren, Education Intern, Providence College

Although there were many Patriots in Rhode Island who supported the Revolutionary War, there were also several Loyalists, or Tories, who sided with the British. Examining attitudes towards Loyalists and the consequences of loyalism both during and after the war offers insight into the ideological divisions within the colonies. Before and during the Revolutionary War, Patriots ridiculed and verbally targeted Loyalists using newspapers and prevented them from gaining political power.

Conflicts between Patriots and loyalists began long before the Revolutionary War started. Several men, who were openly loyal to the monarchy in England, tried to revoke the Rhode Island charter because Rhode Islanders were not willing to pay taxes for their sugar or paper imports. The Loyalists in Rhode Island were a distinct group of people, usually “conservative merchants who were more fearful of armed rebellion and its attendant destruction of trade and constitutional authority than they were of Parliament’s encroachments.” In other words, these Loyalists would have rather preserved their merchant businesses and been under the British Parliament’s rule than take part in a rebellion and develop an independent constitution. In the years and months leading up to the war, some Rhode Islanders remained loyal to the crown because of their reluctance to change, as well as a fear of general disruption instilled by the Patriots’ push for liberty.1Joel A. Cohen, “Rhode Island Loyalism and the American Revolution.” Rhode Island History Journal. v.27, no. 4. October 1968: 97

Many newspapers printed anti-Loyalist sentiments and used harsh language to describe the Tories. One article from 1774 stated, “What pity it is such vermin should not be return’d back to the land of poverty and bondage ahence [from which] they were sent!”2“Mr. Southwick,” The Newport Mercury, November 21, 1774, sec. News/Opinion, 3 Patriots often viewed Loyalists as conspirators trying to keep the American people unaware of their political dependency to Great Britain. Loyalists were also labelled as “foreigners” and “home bred enemies.”3“Mr. Southwick,” 3 Such names were a means of defining Loyalists as inferior and unwelcomed as well as marking them as the enemy. Patriots used newspapers and unkind descriptions to speak against the Loyalists while gaining momentum and support for the Revolution. One newspaper article includes a Patriot’s opinion of Loyalists, in which he described them as “creatures” and claimed that they would “rob, and plunder the inhabitants of these colonies of all their property and then abuse, insult, and murder them, for complaining.”4“To the Printers of the Massachusetts Gazette,” The Newport Mercury, September 26, 1774, sec. News/Opinion, 3 This Patriot writer created a portrayal of Loyalists as a way of encouraging other colonists to side with his views. Claims that depicted Loyalists as murderers were seldom (if ever) based on factual material. In actuality, Rhode Island Loyalists would rarely voice their opinions and political views and avoided violence5Cohen, p.113 As the newspaper article shows, Tories had a reason to fear repercussions for their loyalty to the king.

In 1775, about seventy prominent citizens of Rhode Island signed a document as a means of pledging their loyalty to Great Britain. Their loyalism was primarily motivated by the hope of preserving peace instead of expressing their allegiance to the king. However, many signers sided with the Patriots once they realized war was inevitable. Other Loyalists who remained firmly dedicated to Great Britain were targeted for their views. Jonathan Simpson, who had a hardware store in Providence, had the windows and doors of his store tarred and feathered because of his British loyalties. Within a day after this incident, he fled the city.6Cohen, p.98 Another Tory, Judge Stephen Arnold, also faced the wrath of the Patriots. Residing in East Greenwich, Arnold faced an accusation for holding views that contradicted those of American liberty. A mob hung an effigy of him as a means to make other Loyalists fear similar treatment if they continued siding with the British. These are examples of some of the repercussions for either being a Loyalist or helping a Loyalist in any way.7Cohen, p.99

While the Rhode Island Patriots were happy that Loyalists like Jonathan Simpson left the colony, they did not want Loyalists who fled other colonies to come to Rhode Island, either. For example, a group of Newport Patriots requested that Bostonians ensure that when they remove “any of those vermin, those pests to society, the Tories” that they do not send “any of them to come to plague the town of Newport, where there are already too many outlandish Tories.”8“Advertisement,” The Newport Mercury, April 22, 1776, sec. Advertisement, 2 Some Loyalists had already fled to Newport to avoid being hung or starved in Boston. In turn, Newport Patriots placed threats on the Loyalists as a way of driving them out of the colony.

Because of their unpopularity and smaller number, the Loyalists had very little political say in their local government.9Cohen, pp.100-101 An article in The Newport Mercury asserted that Tories were not allowed to hold any office because they were at the same level as “double tongued monsters.” The Patriots wanted to exclude the Loyalists from having the same political opportunities that they enjoyed because they feared that the Loyalists could not be trusted and would bend to the will of the British government.10“The Following Is a Copy of a Notification Found Stuck up at the Brick-Market in This Town,” The Newport Mercury, January 10, 1774, sec. News/Opinion, 3 Additionally, Patriots wanted to prevent Loyalists from having the ability to sway an election to prevent government officials from enacting Loyalist ideas. The Patriots were particularly defensive of their political freedoms and were unwilling to tolerate any Loyalist threats to their way of government.

In addition to publishing their attitudes towards Loyalists in newspapers, Patriots also used politics to keep Loyalists in check. The instigation of the loyalty oath, or the Test Act, stated that “all males above sixteen who were suspected of holding principles inimical [in opposition] to the American cause were to declare their loyalty and willingness to aid in the colonies’ defense. If anyone refused the oath he then had to relinquish his arms and ammunition to the colony.”11Cohen, p.101 However, the colony would pay the accused for his arms and the Test Act did not apply to Quakers, who pledged nonviolence for religious reasons. An addition was soon made to the Test Act, preventing any male over the age of twenty-one (excepting Quakers) from testifying in court, voting at town meetings, or having a position in military or civil service without pledging the oath.12Cohen, pp.101-102 Patriots used legislation to expose Loyalists and to limit their political liberties if they refused to support their cause.

Because the number of vocal Loyalists in Rhode Island was few, the conflict between the Patriots and the Loyalists was not as intense as in other colonies. Tories usually only became a problem if they spoke up about their views.13Cohen, p.103 However, as noted above, opinion articles printed in newspapers by Patriots and Patriots standing in local governments provided means for Patriots to express their views against Loyalists, keep the Loyalists in line, and limit their influence. Many Tories faced verbal and physical abuse, public ridiculing, and political constraint. As the popular will solidified along Patriot lines, Loyalists were viewed as enemies of the colony, despite being citizens of the colony, just like the Patriots.

Terms:

Loyalist: American colonists who sided with Great Britain during the Revolutionary War and opposed the colonies’ independence

Tory: another name for loyalist in the context of the American Revolution

Patriot: American colonists who opposed British rule in the colonies and wanted independence from Great Britain

Revoke: to make a statement or declaration invalid

Charter: a decree written by a governing power that lists the rights of an organization, such as a colony

Effigy (to hang in effigy): creating and hanging a dummy or likeness of a person, usually one who holds a position of authority, as a way of ridiculing the person. The practice was common prior to and during the American Revolution

Questions

Do you see any similarities between the way newspapers spread opinions and the way that the modern media reports on political topics?

One interesting area that historians study is the rhetoric that was used during the Revolutionary War. Rhetoric refers to writing or speaking persuasively and involves studying the type of language people use. Do you think many of the claims that the Patriots made about the Loyalists in newspapers were factual and valid or do you think they were meant to persuade other Patriots to agree with the authors’ opinions?

Another potentially interesting question: Patriots required men over a certain age to take loyalty oaths. Why do you think women weren’t required to take oaths? Do you think women had their own political loyalties? How do you think they would have expressed those views?

If you were a loyalist, would you have stayed in Rhode Island during the war or fled to another country like England? Why or why not?

- 1Joel A. Cohen, “Rhode Island Loyalism and the American Revolution.” Rhode Island History Journal. v.27, no. 4. October 1968: 97

- 2“Mr. Southwick,” The Newport Mercury, November 21, 1774, sec. News/Opinion, 3

- 3“Mr. Southwick,” 3

- 4“To the Printers of the Massachusetts Gazette,” The Newport Mercury, September 26, 1774, sec. News/Opinion, 3

- 5Cohen, p.113

- 6Cohen, p.98

- 7Cohen, p.99

- 8“Advertisement,” The Newport Mercury, April 22, 1776, sec. Advertisement, 2

- 9Cohen, pp.100-101

- 10“The Following Is a Copy of a Notification Found Stuck up at the Brick-Market in This Town,” The Newport Mercury, January 10, 1774, sec. News/Opinion, 3

- 11Cohen, p.101

- 12Cohen, pp.101-102

- 13Cohen, p.103