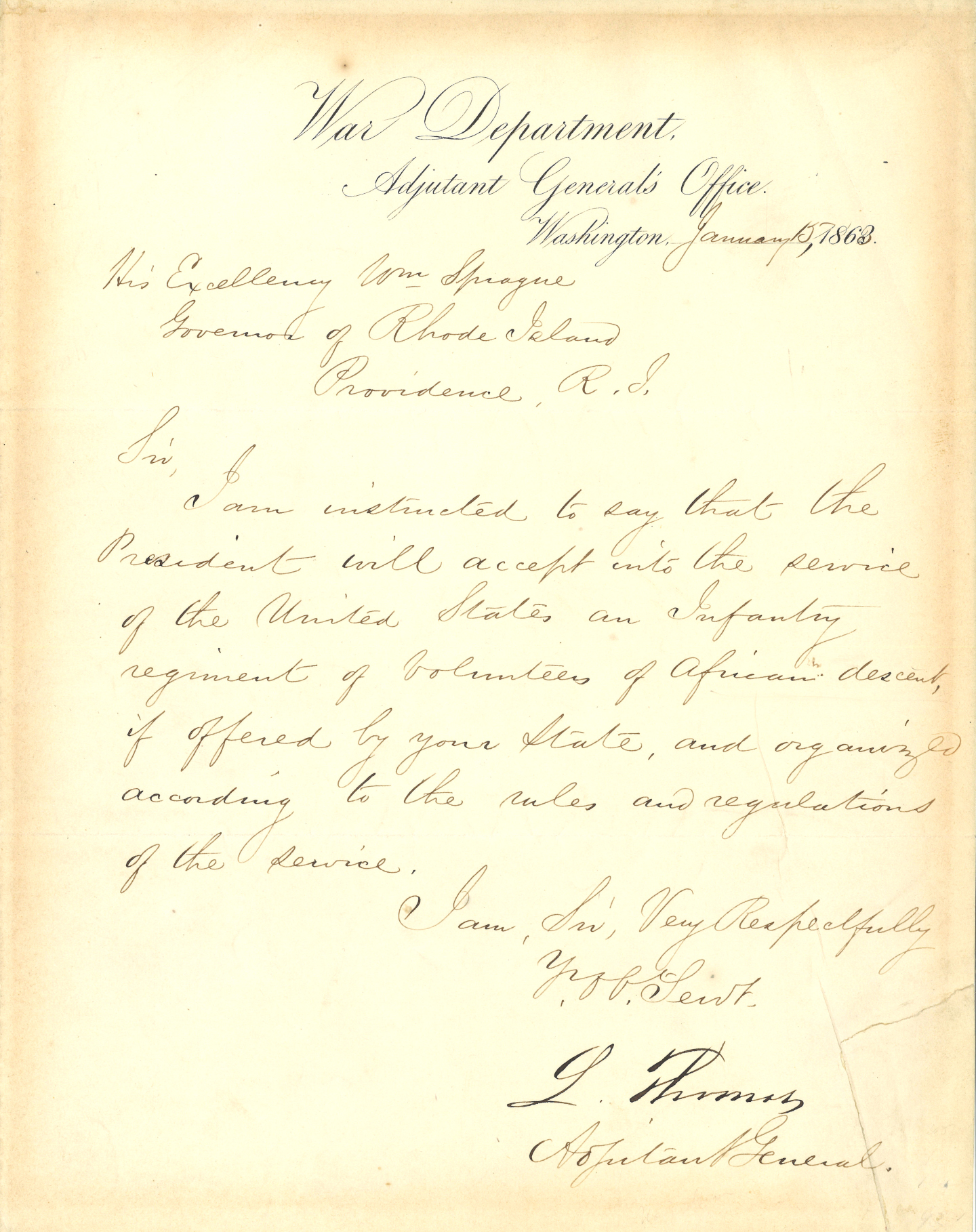

Letter to Governor William Sprague to Accept Volunteers of African Descent

Written just two weeks after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, this letter was sent to Governor William Sprague (1830–1915) from Lorenzo Thomas, Adjutant General, inviting Rhode Island to contribute “an infantry regiment of volunteers of African descent.” Hundreds of Black men from Rhode Island volunteered to form the 14th Heavy Artillery regiment.

Acquired from an online auction with the generous support of the Varnum Continentals.

The 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery Unit (Colored): Serving With Distinction In the Face of Resistance

Essay by Jackson Piantedosi, Rhode Island Historical Society Education Intern, student at Providence College

African Americans played important roles in freeing themselves and other Black people during the Civil War. Early in the war, many enslaved black people escaped from Southern plantations and headed into Union lines, a movement that only accelerated after President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863. The Union then recruited Black volunteers for the military. By the war’s end, almost 180,000 Black soldiers had served in the Army and an additional 19,000 in the Navy. Over 40,000 men died—three-quarters of them from disease.1According to Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments that Redeemed America (by Douglas Egerton, NY: Basic Books, 2016), 178,975 African Americans fought for the U.S. (North); of them, 140,313 were Black Southerners recruited either in loyal slave states or from the Confederacy; 2,751 died in action, and 65,427 died of disease or went missing

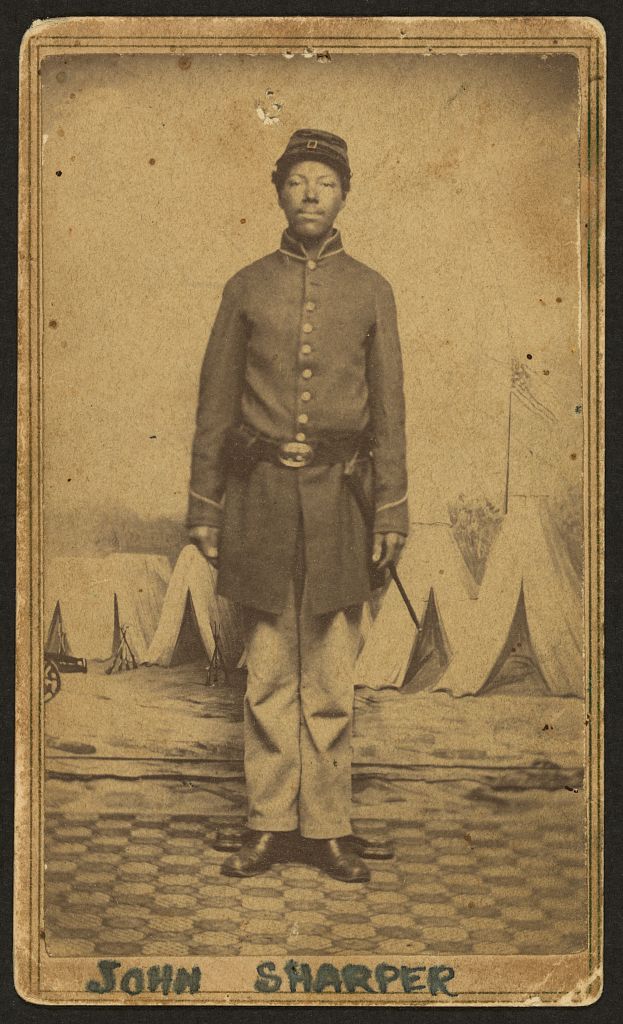

Black soldiers first saw combat in July 1863, shortly after the battles of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, when the 54th Massachusetts suffered heavy casualties in the assault on Fort Wagner. Because of racial prejudice, all officers of Black regiments were White, but as the war went on, Black soldiers increasingly won respect for their courage.2Sixteen African Americans received the Medal of Honor It took special courage for Black soldiers to serve because Confederate officers often refused to treat captured African Americans as prisoners of war and instead executed them as escaped slaves. Even White officers of the Black units were executed because they were deemed traitors.3General Orders, No. 111. Proclamation by the Confederate President. Richmond [Va.], December 24, 1862. Electronic Document. Accessed on November 14, 2020 [link]; James G. Hollandsworth, Jr. “The Execution of White Officers from Black Unites by Confederate Forces during the Civil War.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Autumn, 1994), pp. 475-489

In January of 1863, Governor William Sprague IV received a letter from authorities in Washington to “…accept into the service of the United States an Infantry regiment of volunteers of African descent, if offered by your state, and organized according to the rules and regulations of the service.”4Letter from Lorenzo Thomas to Governor William Sprague (RI) Washington, DC: 15 January 1863. Rhode Island Historical Society Collections This followed the instatement of the Emancipation Proclamation that went into force on January 1. It wasn’t until a May order from the United States War Department creating the Bureau of Colored Troops designated Black regiments as United States Colored Troops. In June, Rhode Island’s then-Governor James Smith began to form a “colored” Heavy Artillery Company. The 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored)5The regimental designation changed throughout the War. It became the 8th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment in April of 1864, and finally 11th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery in May 1864 was mustered on August 28, 1863. Its men joined more than 25,000 Black artillerymen who served in the Union armies.6Cunningham, Roger D. “Black Artillerymen from the Civil War through World War I.” Army History, no. 58 (2003): 4-19. [link]; Frank Gryzb. “The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) During the Civil War.” Small State Big History. March 5, 2020. [link] The Rhode Island unit was the only Black artillery regiment raised north of the Mason-Dixon line. As was set by the national policy, all of the 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) unit’s commanding officers were White.

Black men enlisted rapidly, and the company quickly grew to the size of a full regiment of twelve companies. With emancipation now a central goal of the Union cause, African Americans supported the war enthusiastically. Many Whites, however, did not hold the regiment in high regard, including the future captain of companies H and L, Joshua Melancthon Addeman, who wrote in his memoirs, “In common with many others I did not at the outset look with a particular favor upon the scheme.”7Addeman, Joshua M. Reminiscences of Two Years with the Colored Troops. Hardpress Publishing, 2012 The regiment reported for training at Camp Smith, which was named after Governor James Smith of Rhode Island “in recognition of the untiring efforts of the governor in raising and equipping the regiment,” at the Dexter Training Ground in Providence. As the regiment grew, they moved to Dutch Island in Narragansett Bay.8Chenery, William H. The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) in the War to Preserve the Union, 1861-1865. University Publications of America, 1991; Frank Gryzb. “The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) During the Civil War.” Small State Big History. March 5, 2020. [link]

Early in 1864, the regiment was transported, via the steamer Daniel Webster, to its post outside of New Orleans. It was not an easy trip, plagued by tight quarters and a lack of drinking water. Phanuel E. Bishop, a captain of the 14th Rhode Island, wrote in his diary about the conditions of the voyage to New Orleans, “There is quite a swell on the sea, and many are paying their debts to Old Neptune, god of the deep. In other words, some are seasick.”9Bishop, Phanuel. Diary of Phanuel E. Bishop., MSS 9001-B, Box 7, Rhode Island Historical Society Despite the difficult conditions, the regiment arrived in New Orleans, having only lost two men on the voyage.

The regiment was deployed, like most Black units, to man the larger caliber guns defending coastal and field fortifications near cities.10Cunningham, Roger D. “Black Artillerymen from the Civil War through World War I.” Army History, no. 58 (2003): 4-19. [link] While their duty was ordinary, the quality of their service, however, was often distinguished. Their service in Union-occupied New Orleans, and later at Fort Esperanza in Texas, served as an example to all Union regiments and eventually received high praise from Governor Smith himself.

In a letter to Smith, Major Joseph J. Comstock, Jr. proudly reported the condition of his regiment, detailing its exceptional discipline and energy. In one example, “The assembly was sounded, and in five minutes the whole battalion, four hundred strong, was in line, and I have never found a regiment, even on a Sunday morning inspection, in a more perfect condition… excellence is the proper term to apply to its conditions.”11Comstock, Joseph. Letter to Governor James Smith of Rhode Island. 27 January 1864, in Comstock Family Papers, MSS 169, Box 7, Rhode Island Historical Society Despite the sweltering heat, the swampy land, and the constant risk of dehydration and disease, the 14th Rhode Island was “an example to the troops of whatever state.” Less than a month later, Governor Smith’s response reached the regiment, and it is clear he was proud of the regiment’s condition. He writes, “The 14th Regiment will, I am confident, fully sustain the position you have given to the 1st battalion.” The correspondence was shared with the officers of the regiment, as evidenced by Governor Smith’s letter appearing word-for-word in the diary of captain Phanuel E. Bishop. Despite the praise from the highest office in the state of Rhode Island, the men of the regiment frequently experienced discrimination and racism from the citizens they were there to protect.

Captain Addeman explained this hostility in his memoirs, describing, “the scowling looks of white spectators,” and especially noted the derogatory names the troops were called by onlookers.12Addeman, Joshua M. Reminiscences of Two Years with the Colored Troops. Hardpress Publishing, 2012 Often, Confederate prisoners were treated better than the Rhode Island soldiers, and Captain Addeman noted “their comparatively comfortable living quarters and abundant supplies,” which, he said, “afforded a vivid contrast to the treatment received by our boys.”13Addeman, Joshua M. Reminiscences of Two Years with the Colored Troops. Hardpress Publishing, 2012

On August 5, 1864, a detachment of the regiment underwent a surprise attack from a Confederate party. Three soldiers, Privates Samuel O. Jefferson, Anthony King, and Samuel Mason, were captured and then executed the following day. They were the only men from the 14th Rhode Island who were killed by Confederate soldiers. Most who had died did so from disease. Poor conditions and scant medical supplies led to dysentery, malaria, measles, swamp fever, typhoid fever, smallpox, and consumption. Of all of Rhode Island’s regiments and batteries, the 14th Regiment sustained the highest number of deaths.14Frank Gryzb. “The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) During the Civil War.” Small State Big History. March 5, 2020. [link]

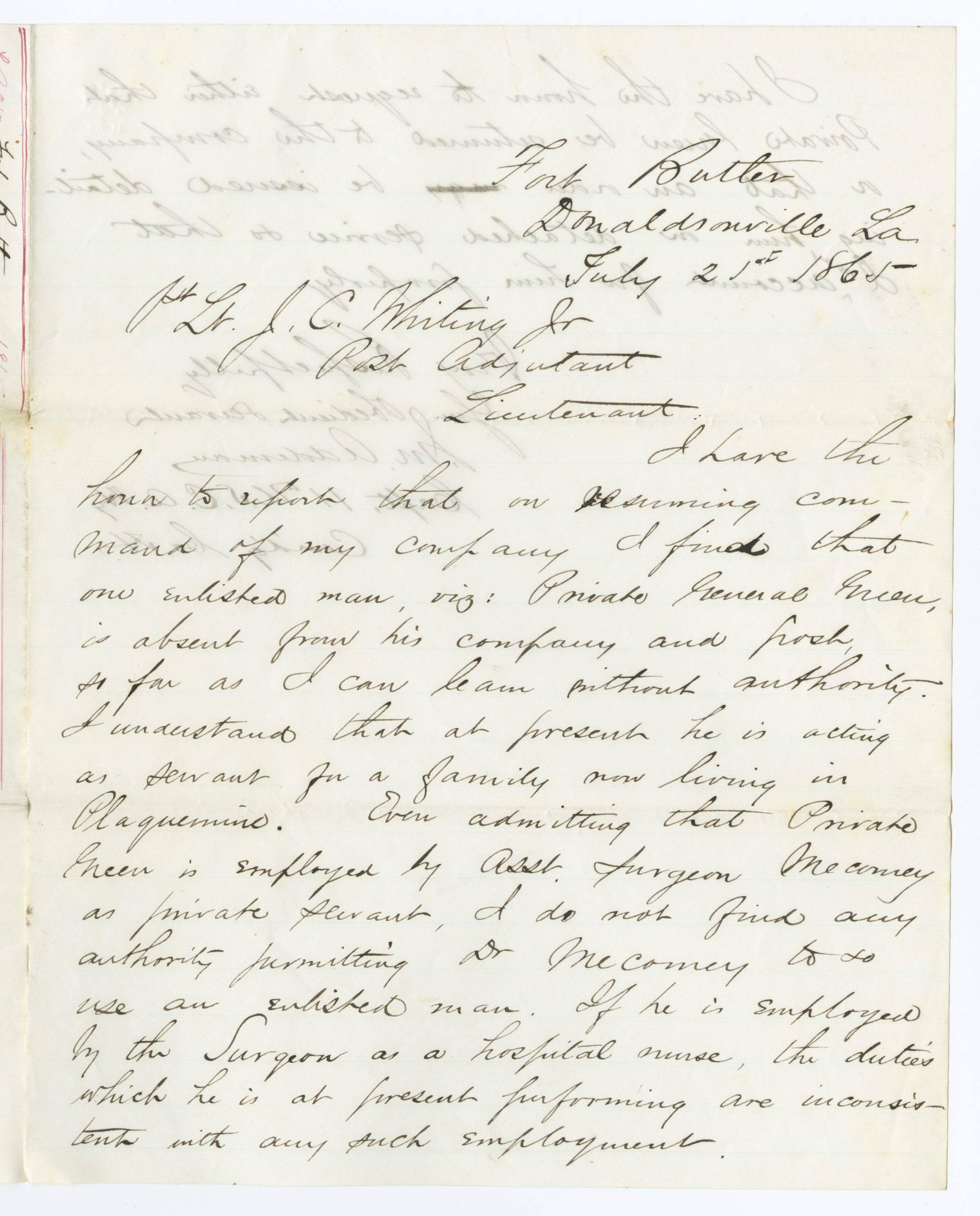

Even after the war ended, discrimination continued. On July 21, 1865, three months after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Addeman observed that one of his soldiers was being used as a servant without his authorization “for a family now living in Plaquemine.” Apparently, the head of the family was a surgeon who claimed Private Green was being used as a nurse.15Addeman, Joshua. Letter to Lt. J. C. Whiting Jr., 21 July 1865, in Joshua Melancthon Addeman Papers, MSS 252, Box 7, Rhode Island Historical Society Addeman suspected he was being used as a household servant: “If he is employed by the Surgeon as a hospital nurse, the duties which he is at present performing are inconsistent with any such employment.”

With the war over, and the freedom of African Americans now guaranteed by the Constitution, the 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) was no longer needed and was mustered out of service on October 2nd, 1865, in New Orleans.16Their designation had been changed to the 11th United States Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment by the time they were mustered out Upon their return to Providence, the regiment was greeted with “a dress parade [that] took place in the presence of His Excellency Gov. James Y. Smith and staff, and an immense course of spectators.”17Chenery, William H. The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) in the War to Preserve the Union, 1861-1865. University Publications of America, 1991

Since then, however, history has largely forgotten the contributions and sacrifices made by the men of the 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored). The unit did not participate in any famous battles, like the Massachusetts 54th, which was featured in the 1989 film “Glory.” William Harvey Carney the first African American to receive the Medal of Honor, was a member of the Massachusetts 54th.

The 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored), however, proved to be an exemplary regiment, carrying out essential duties consistently and responsibly. The brave men who comprised it should be remembered as, in the words of one historian, “noble souls” who risked “their lives for the preservation of this republic, the blessings of which we and our descendants now fully enjoy.”18Chenery, William H. The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) in the War to Preserve the Union, 1861-1865. University Publications of America, 1991

Terms:

Mustered: bringing together troops for military service

Mason-Dixon Line: the generally accepted boundary between the North and the South, running along the southern border of Pennsylvania

Questions:

Why do you think some people were initially resistant to the idea of a colored unit, as Captain Addeman explains?

Despite the fact that Blacks were not allowed to serve alongside Whites, why do you think that all of the 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored)’s commanding officers were White?

- 1According to Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments that Redeemed America (by Douglas Egerton, NY: Basic Books, 2016), 178,975 African Americans fought for the U.S. (North); of them, 140,313 were Black Southerners recruited either in loyal slave states or from the Confederacy; 2,751 died in action, and 65,427 died of disease or went missing

- 2Sixteen African Americans received the Medal of Honor

- 3General Orders, No. 111. Proclamation by the Confederate President. Richmond [Va.], December 24, 1862. Electronic Document. Accessed on November 14, 2020 [link]; James G. Hollandsworth, Jr. “The Execution of White Officers from Black Unites by Confederate Forces during the Civil War.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Autumn, 1994), pp. 475-489

- 4Letter from Lorenzo Thomas to Governor William Sprague (RI) Washington, DC: 15 January 1863. Rhode Island Historical Society Collections

- 5The regimental designation changed throughout the War. It became the 8th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment in April of 1864, and finally 11th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery in May 1864

- 6

- 7Addeman, Joshua M. Reminiscences of Two Years with the Colored Troops. Hardpress Publishing, 2012

- 8Chenery, William H. The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) in the War to Preserve the Union, 1861-1865. University Publications of America, 1991; Frank Gryzb. “The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) During the Civil War.” Small State Big History. March 5, 2020. [link]

- 9Bishop, Phanuel. Diary of Phanuel E. Bishop., MSS 9001-B, Box 7, Rhode Island Historical Society

- 10Cunningham, Roger D. “Black Artillerymen from the Civil War through World War I.” Army History, no. 58 (2003): 4-19. [link]

- 11Comstock, Joseph. Letter to Governor James Smith of Rhode Island. 27 January 1864, in Comstock Family Papers, MSS 169, Box 7, Rhode Island Historical Society

- 12Addeman, Joshua M. Reminiscences of Two Years with the Colored Troops. Hardpress Publishing, 2012

- 13Addeman, Joshua M. Reminiscences of Two Years with the Colored Troops. Hardpress Publishing, 2012

- 14Frank Gryzb. “The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) During the Civil War.” Small State Big History. March 5, 2020. [link]

- 15Addeman, Joshua. Letter to Lt. J. C. Whiting Jr., 21 July 1865, in Joshua Melancthon Addeman Papers, MSS 252, Box 7, Rhode Island Historical Society

- 16Their designation had been changed to the 11th United States Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment by the time they were mustered out

- 17Chenery, William H. The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) in the War to Preserve the Union, 1861-1865. University Publications of America, 1991

- 18Chenery, William H. The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) in the War to Preserve the Union, 1861-1865. University Publications of America, 1991