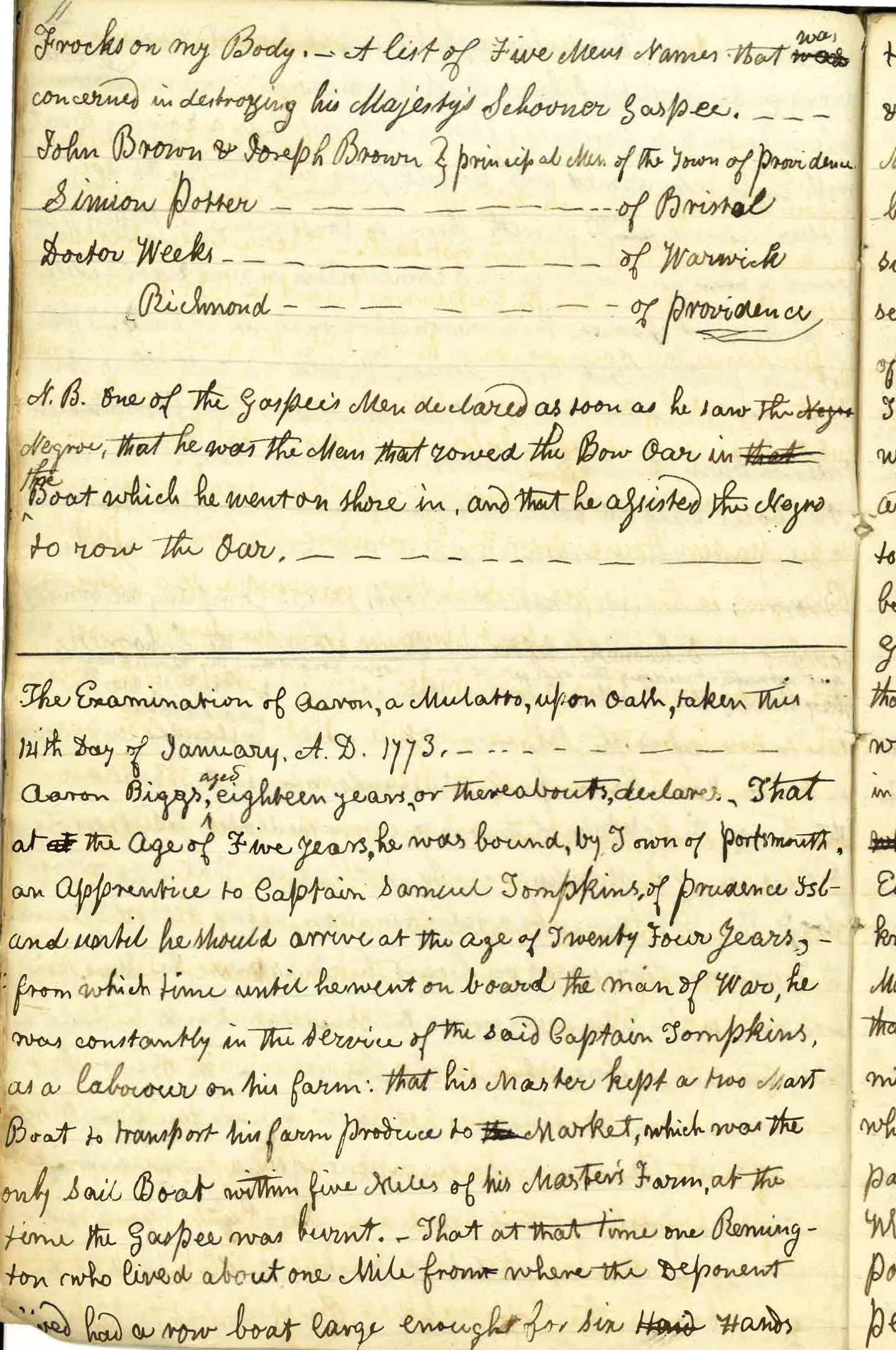

Copy of the testimony of Aaron Briggs

Aaron Briggs gave this statement to the crew of the ship Beaver, and it was sent to Governor Wanton as evidence against John Brown and other prominent merchants. This is a hand-written copy made from the first page of his testimony.

Aaron Briggs: Willing Participant or Weary Prisoner?

Sean Gray, Rhode Island Historical Society Intern, Student at Providence College

Fed up with paying taxes to the British, the American colonists revolted and won their freedom and independence. While that simplistic understanding of the Revolution is not wrong, it ignores how the conflict between Britain and her colonies had different meanings for different people. While wealthy white Americans complained about how Britain was turning them into slaves with new taxes and laws in the early 1770s, these white Americans often held Black people in slavery at the same time. Enslaved Black people, in turn, had their own desire for freedom, but in order to get it, they often had to take extreme measures.

The destruction of the Gaspee and the investigation that followed illustrate the complex and often competing interests of Black and white Americans in the American Revolution. Soon after the Gaspee was destroyed, Rhode Island Governor Joseph Wanton issued a proclamation demanding information about the attack, and he offered one hundred pounds to anyone who came forward. Despite such a promising reward, no Rhode Islanders came forward with any information for almost a month. The investigation into the attack had seemed to reach a dead end.

That changed in early July, when a multiracial young man named Aaron Briggs, born to a Black father and a Narragansett mother, fled his home on Prudence Island in Narragansett Bay to the British ship Beaver stationed nearby. He confessed that he had participated in the Gaspee raid. Historians have argued about Briggs: who he was, whether he was an indentured servant or enslaved, and why he fled to the Beaver. None of these things are certain because there are few surviving documents about Briggs, which is typical for a man of his station. When he fled, Briggs was not a free man, and studying his escape can help us understand how the American Revolution meant different things to different people.

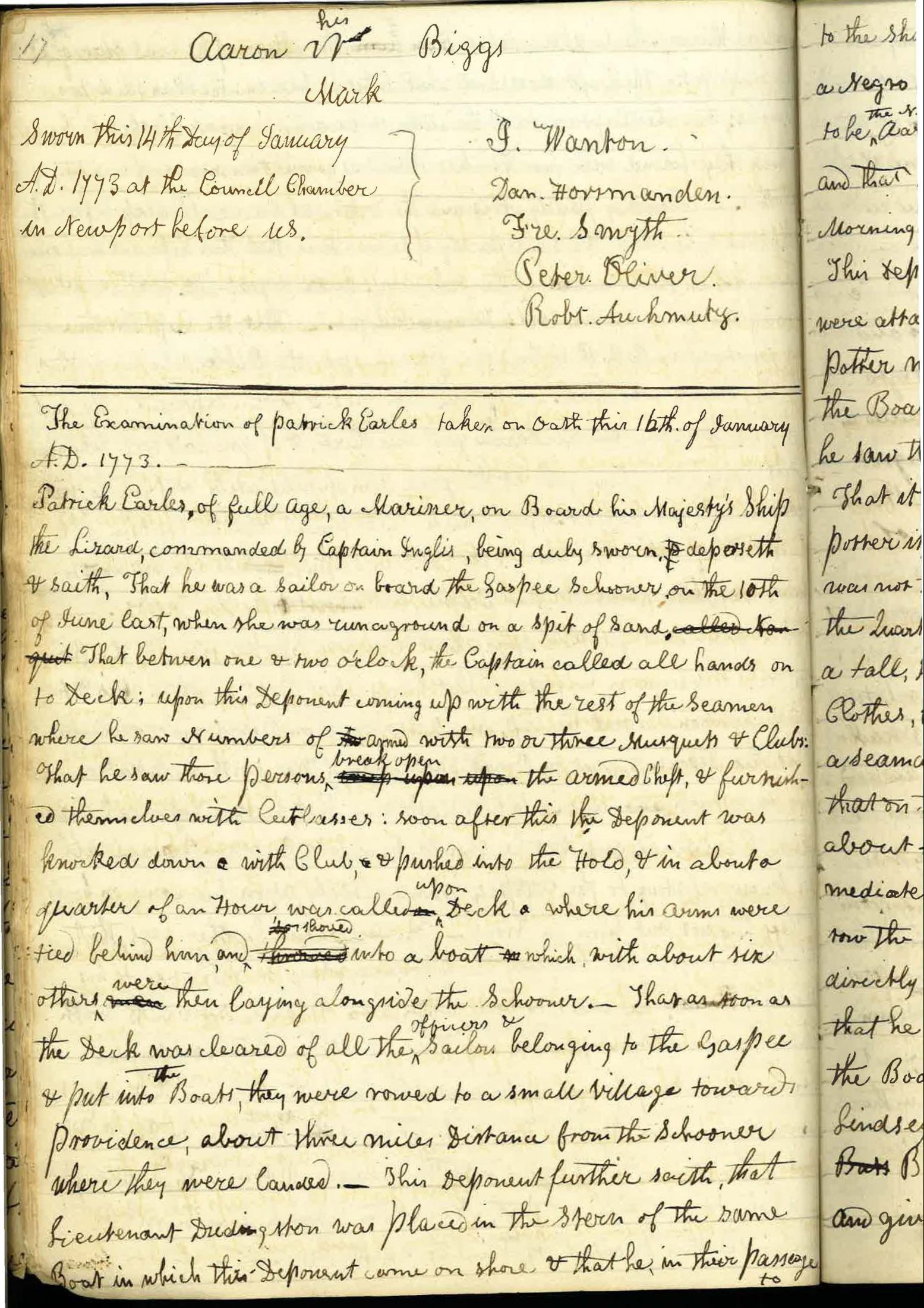

At the age of five, Briggs was abandoned by his parents and left to the care of the government. Samuel Thompkins, a farmer from Prudence Island, eventually took charge of him, and Thompkins held Briggs as either an indentured servant or in enslavement. Briggs lived and worked on Prudence Island until July 1772, when he fled to the Beaver.1Charles Rappleye, Sons of Providence: The Brown Brothers, the Slave Trade, and the American Revolution. New York: Simon and Schuster. 2006. p. 116

In his testimony to the crew of the Beaver, [transcribed version of the testimony here] Briggs made three important claims about the Gaspee’s destruction. First, he said that Simeon Potter of Bristol, a slaveholder, impressed him into service while Briggs was rowing near Prudence Island, his home less than ten miles from the site of the attack, on the night of June 9. Second, Briggs said that he saw John Brown shoot William Dudingston, almost killing the lieutenant. Finally, Briggs closed his testimony with the names of five prominent Rhode Islanders who he claimed planned the attack: John Brown, Joseph Brown, Simeon Potter, a “Dr. Weeks of Newport,” and a “Richmond of Providence.”

Admiral John Montagu, Lieutenant Dudingston’s superior stationed in Boston, was thrilled to hear Briggs’ story. Up to this point, the only witnesses who had come forward were Gaspee crew members, and Briggs’ story matched up well with theirs. More importantly, as a local, Briggs identified specific men involved with the raid—something the crew of the Gaspee could not do. After a month without progress, Montagu hoped that Briggs’ testimony could jumpstart the investigation. In a letter on July 8th with Briggs’ statement enclosed, Montagu ordered Governor Wanton to arrest John Brown and Simeon Potter for their leadership in the raid.2Admiral Montagu to Joseph Wanton, July 8, 1772, in Colonial Records of Rhode Island, ed. John Bartlett (1862), 93 In order to maintain peace within the colony, however, Wanton knew that he could not arrest the powerful Brown and Potter. He quickly set out to investigate Briggs’ story.

Only days after receiving Montagu’s letter, Wanton deposed four men whose testimonies directly contradicted Briggs’ story. Two of the four men, Samuel Thompkins and Samuel Thurston, were farmers on Briggs’ home of Prudence Island. The other two, Somerset and Jack, were their indentured servants, and both shared a room with Briggs. Joseph Wanton took their statements on July 11. [A transcription of the testimony can be found here]. Somerset and Jack claimed that there was no way Aaron Briggs could have been involved in the burning of the Gaspee, because they had shared a bed with him that same evening. Moreover, they claimed that before his escape to the Beaver in July, Briggs had not left Prudence Island for months. Finally, Somerset and Jack said that since the events of June 9, Briggs had not mentioned the Gaspee affair or his involvement. Thurston and Thompkins both agreed with their servants, and each added that the boat Briggs claimed to row that night was actually broken at the time. The four men suspected that Briggs had merely heard the story of the Gaspee’s destruction and, thinking that service as a witness could lead to freedom, fled to the Beaver and lied to the crew.

These four testimonies, however, do not necessarily reflect the truth of the story. Thompkins and Thurston were likely eager to get Briggs home and back to work, and discrediting his testimony could make that happen faster. Somerset and Jack, as their servants, could have been coerced into making the statements that they did. These two men, along with Briggs, were not entirely free—Thompkins and Thurston could hold them accountable for their words, and the threat of punishment and violence certainly loomed over their heads as they spoke to Wanton. While these relationships seem strange today, many men and women in the eighteenth century were not legally free: some were enslaved, permanently bound to servitude, and others were indentured servants who were held in servitude for a number of years. These “unfree” legal statuses were common across the colonies, and many people lived under the hand of others.

After hearing these testimonies, Governor Wanton wanted to question Briggs himself, but the crew of the Beaver refused to hand him over. Fearing for Briggs’ safety after he had implicated some of Rhode Island’s most powerful men in the Gaspee affair, the British held him aboard the boat for months. He was their best witness, and they did not want to take any unnecessary risks with his life.

Six months later, on January 14, 1773, Briggs finally testified in front of Wanton, as well as the rest of the commission investigating the destruction of the Gaspee.3Read about the commission in our essay Governor Joseph Wanton and the Controversial Commission [link] There, Briggs restated much of his first testimony. When he spoke about his time aboard the Beaver, however, it seemed as if the captain of the ship forced Briggs to make up his story. Briggs described being chained up and threatened with beatings, only to be saved at the last second once a Beaver crewman claimed to recognize him from the raid. Patrick Earle, formerly a sailor on the Gaspee, said that he and Briggs had rowed together on June 9, as the Gaspee was evacuated. Earle testified before the commission immediately after Briggs’ testimony. He corroborated much of Briggs’ story from July. Earle said that he sat next to Briggs as the Gaspee was being evacuated. He then encountered Briggs again in July when Briggs came to the Beaver. Afterward, one of Wanton’s investigators observed that it was likely too dark for Earle to recognize anyone from the night of the burning. Moreover, the possibility that the Beaver’s captain forced Briggs to make up his story seriously affected Briggs’ credibility. The commission continued to question witnesses for another two weeks, and then adjourned until the summer.

In the commission’s final report, released in June of 1773, the group concluded that Briggs’ testimony was “made in consequence of illegal threats from Capt. Linzee [of the Beaver] of hanging him.” The commission believed that Captain Linzee had forced Briggs to make the story up in order to help the investigations. In a private letter, one of the investigators even believed that Patrick Earle had prepared Briggs to testify, coaching him about proper answers to questions from the commissioners.4Steven Park. The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee: An attack on crown rule before the American Revolution. Westholme Publishing: Yardley, PA. 2016. p.128 Both the life-threatening circumstances Briggs faced on the Beaver and the contradictory depositions of Samuel Thompkins, Somerset, and Jack made Briggs’ story unbelievable to the commission. Additionally, the only people Briggs implicated were well-known throughout the colony, and rumors about their involvement had spread long before Briggs fled to the Beaver. Having lost their last credible witness, the Gaspee commission concluded their investigation without any arrests.

Little is known about Aaron Briggs’ life after the commission disbanded. Since he was abandoned as a child, he likely had no family to return to. He might have returned to Prudence Island to face whatever consequences Thompkins and Thurston might dole out. Yet that would have been incredibly dangerous, given how many Rhode Islanders he angered with his testimony. The Gaspee Days Committee, a modern-day local group dedicated to studying the Gaspee raid, has tried to trace his life through the Revolutionary War and beyond, but much of their work is speculative. Others have theorized that Briggs was allowed to join the British Navy since he was no longer safe in Rhode Island. None of this can be said with certainty, however.5After much research, including the Gaspee Day Archives Website and literature surrounding the Gaspee Affair and Briggs’ life, like Stephen Park’s work, it is not clear what happened to Briggs. Since there’s no data to prove what happened to him sufficiently, I conclude that any ideas about his life after the Gaspee are merely speculative.

Still today, disagreements remain about whether or not Aaron Briggs was actually involved in the destruction of the Gaspee. On their official website, the Gaspee Days Committee lists Aaron Briggs as “one who took part, willingly or unwillingly, in the attack.” Many historians tend to disagree. They often cite the depositions of Thompkins, Somerset, and Jack, the final report of the Commission, and the private letters of the commissioners as evidence that Briggs fabricated his story under pressure from Captain Linzee and the crew of the Beaver. Nevertheless, we should not forget that Governor Wanton wanted to disprove Briggs’ story in order to maintain peace in the colony. Moreover, the commissioners may have viewed his story differently because he was a runaway Black man.

We might never know if Briggs was involved in the raid, but an arguably more important question remains: why did Briggs flee to the Beaver in the first place? He may have heard about how other enslaved Black men, like Crispus Attucks, a victim in the Boston Massacre, fled from their birthplaces in order to be free. Briggs might also have seen the number of Black mariners, or as one historian has dubbed them, “Black Jacks,” at seaports across Rhode Island and considered the seas his best option to get as far away from Prudence Island as possible.

What is clear is that Briggs’ story complicates our understanding of the destruction of the Gaspee. For some, like Governor Wanton or Lieutenant Dudingston, it was a conflict over colonial rights and independence. Yet for Aaron Briggs, an unfree multiracial teenager, the Gaspee’s destruction had far more real consequences: it served as a potential pathway to liberation for him. What do you think? Was Aaron Briggs looking for freedom in his flight to the Beaver, or did he really participate in the burning of the Gaspee?

Terms:

Proclamation: a public announcement regarding an important matter

Multiracial: a person who has parents of more than one race

Indentured Servant: an unpaid laborer who receives freedom in exchange for a set number of years of service

Impress: to force someone to serve in the military against their will

Depose: to question a witness

Coerce: to force someone to do something by threats or violence

Implicate: to say that someone is involved in a crime

Commission: a group of people tasked with investigating an important event

Corroborate: to support or confirm someone else’s testimony

Credibility: being a trustworthy source of information

Adjourn: to end a meeting with a plan to meet again in the future

Testify: to serve as a witness in a court

Speculative: based on incomplete information; a theory

Questions:

Why was the British Admiral Montagu excited about Briggs’ testimony? Why was RI Governor Wanton so ready to disprove it?

Why was Briggs not safe in Rhode Island after fleeing to the Beaver?

Overall, was Aaron Briggs a credible witness? Why or why not?

- 1Charles Rappleye, Sons of Providence: The Brown Brothers, the Slave Trade, and the American Revolution. New York: Simon and Schuster. 2006. p. 116

- 2Admiral Montagu to Joseph Wanton, July 8, 1772, in Colonial Records of Rhode Island, ed. John Bartlett (1862), 93

- 3Read about the commission in our essay Governor Joseph Wanton and the Controversial Commission [link]

- 4Steven Park. The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee: An attack on crown rule before the American Revolution. Westholme Publishing: Yardley, PA. 2016. p.128

- 5After much research, including the Gaspee Day Archives Website and literature surrounding the Gaspee Affair and Briggs’ life, like Stephen Park’s work, it is not clear what happened to Briggs. Since there’s no data to prove what happened to him sufficiently, I conclude that any ideas about his life after the Gaspee are merely speculative.