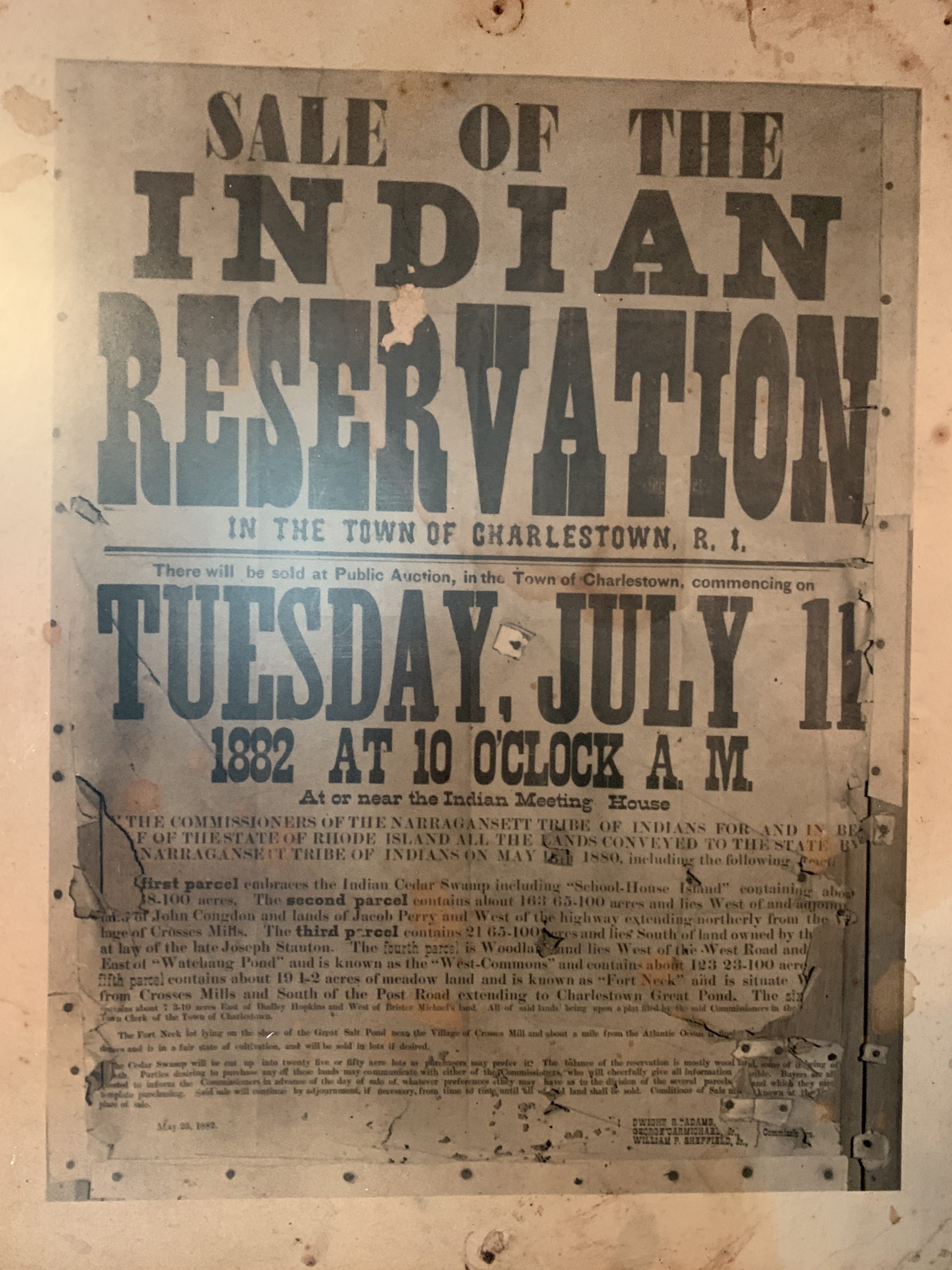

Broadside for the Sale of the Indian Reservation

This broadside from the collections of the Tomaquag Museum advertises the sale of the Narragansett Indian reservation that took place on July 11, 1882 following the detribalization of the Narragansett people.

Detribalization to Federal Recognition: A political, social, economic defining of Identity

Essay by Lorén Spears, MsEd., Narragansett, Executive Director of Tomaquag Museum

Who decides identity? A person? A people? The United States government? The State of Rhode Island? This is a complex issue for the Indigenous Peoples of this land now called the United States of America. The Narragansett Indian Tribal Nation is the only federally recognized tribe in Rhode Island. The Narragansett were here for thousands of years prior to colonization and conquest and have survived 400 years since the Mayflower landed. It suffered detribalization and then succeeded in gaining Federal Acknowledgement and Recognition.

What is a tribal nation? It is a kinship relationship of people connected through birth, marriage, adoption, and familial ties such as parents, children, siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, grandchildren, in-laws, and so on. Kinship relationships are connected by clan, village, tribe, and nation. The Narragansett had a vast kinship network that tied the community together with leadership from each family, clan, and village to represent the tribe or nation within its governmental structure. “In our tribal nation, historically, we had sachems or sub-chiefs as well as a supreme sachem who lead in a format that was more like a democracy whereby the people had a strong voice on the decisions for the community.”1Williams, Roger. “Chapter 22” in A Key into the Language of America, edited by Dawn Dove, Dorothy Herman Papp, Sandra Robinson, Lorén Spears, and Kathleen Bragdon, The Tomaquag Museum ed., 119. Westholme Publishing, 2019. This included Sauncksqua, or female leaders or chiefs, as well as Ataùskawawwáuog, or Councilors. All of these roles continue into the 21st century, but the ways in which they are achieved are different than long ago.

Many things led to detribalization. The first fifty years of English colonial settlement (~1620-1670) led to the dispossession of land holdings of the Narragansett and Niantic peoples. Rather than holding lands throughout the geographic area of what became the State of Rhode Island, Indigenous land holdings were reduced to the area of what is now Washington County. King Phillip’s War led to the shift of power in the region. Genocide, displacement, enslavement, and forced assimilation was an ongoing struggle for the First Peoples. You can learn more about this history in this module’s main essay.

Throughout our state’s history, federal, state, and local governments employed tactics meant to erase, eradicate, or “de-Indianize” the Indigenous population. For example, on official documents such as birth certificates, military records, school records, and marriage licenses, those creating the records would identify a person as “colored”, “mulatto”, “mustee,” or “black” rather than “Indian” even if earlier records of the same person identified them as such. The idea of needing to prove a required blood quantum was a policy adopted by the United States government through the Indian Reorganization Act of 19342See “Will current blood quantum membership requirements make American Indians extinct?” from the National Museum of the American Indian for more information. [link] and also informally used to fulfill the Dawes Act of 1887, also known as the Allotment Act, in which individual Indian people were given an allotment of the lands held communally. Individuals were enrolled by the Office of Indian Affairs (now Bureau of Indian Affairs), a department of the U.S. government, based on their blood quantum. The notion of blood quantum erased Native ways of knowing kinship relationships of family, clan, and community. The policy also reduced the number of people who were recognized as being “Indian,” and thus reduced Indian populations. This reduced the number of people allowed to receive allotted land or caused the dissolution of Indian titles to land, sometimes within a generation or two. The goal of this policy was to cause a complete eradication of the Indigenous population, although it was not achieved. The sentiment “There is no good Indian, but a dead Indian” is a much-remembered quote attributed to General Phillip Sheridan, though he denied having said as much. Whether the quote was ever said or not, the sentiment remained part of United States lore, practice, and policy. It points to the above notions of eradicating the Indigenous population over time.3For more information see Blood Quantum Native American: Definition, Facts & Laws [link] as well as All My Relations Podcast episodes 10 & 11. [link]

Another strategy used to dissolve tribal nations was through propaganda or enforcing the myth of the “vanishing Indian.” Throughout the country, myths memorializing the First Peoples and mourning the last of their kind were promoted. For example, author Theodora Kroeber wrote Ishi in Two Worlds: a Biography of the Last Wild Indian in North America in 1861, and James Fenimore Cooper wrote The Last of the Mohicans, a fictional novel, in 1826. As the country modernized, promoting the stereotype of the “vanishing Indian” became the main way for European Americans to deny an identity as Americans and thus deny civil and land rights to Indigenous peoples while creating a new “American” identity that they could claim for themselves. We are not just dispossessed of our land and way of life, but also denied our identity as “Indian” in the modern world.4Jean M.O’Brien, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence. University of Minnesota Press. 2010

The State of Rhode Island detribalized the Narragansett between 1880 and 1883, the same time period as the Allotment or Dawes Act was implemented out west. Detribalization is the forced abolition of a tribal community or nation through legal action by the colonizing government, resulting in the loss of tribal identity, allegiance, customs, land, and land rights. It was another means to dispossess the Narragansett Tribal Nation of their land, inherent rights to use of the land and its resources, and to force Narragansett people to assimilate into the White majority Rhode Island and United States culture. Assimilation included Christianization, modernization, westernization, and systematic dismantling of the Indigenous community’s language and cultural, ecological, historical, and land-based knowledge for not only the Narragansett but for tribal nations across America. Thus, this added to the “disappearing Indian” mythology. Through detribalization, members of the Narragansett Nation officially became citizens of the state of Rhode Island and the United States. According to a Memorandum from the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs regarding federal acknowledgment dated July 29, 1983, the State paid $5000 in total to the 324 people on the detribalization list. The 927 acres of land held in common or communally by the Tribe at this time was removed from the tribe, except the 2 1/2 acres surrounding the Indian Church.

Representatives from Narragansett families signed the detribalization rolls to be put on this list, and the list would later include their family members, such as parents, children, and grandparents. Many people did not want to sign the detribalization rolls and sent their children to do so. “The first list are people who were paid for the reservation in Charlestown, the only remaining land, with exception of the church, of the Narragansett Tribe of Indians. They were wards of the State and after the sale, were made citizens of R. I. and U. S. They were Indians then. What are they now?”5Narragansett Dawn , April 1936, p282-284. [link]

Many protested. Some families refused to sign. Others fled north and then joined other Indian Americans in Brothertown, Wisconsin, to protect and preserve cultural lifeways.6See the main essay of this module for more information about the movement to Brothertown. [link] Not all Narragansett people were signed onto the rolls, nor were they all documented. Not being represented on the rolls at that time continues to have lasting effects on the Narragansett community today. Narragansett people who cannot link themselves to the people on these rolls are not considered citizens of the Narragansett Indian Tribal Nation, however this does not mean they are not Native American or Narragansett. This is a complexity related to federal recognition policies.

“In 1880, the reservation was bought by the state and the Indians made citizens of the state. Then a law was passed that the Narragansetts could no longer teach their children the Indian tongue or rituals. They were to be citizens and live as everyone else did. Still, they had their school and church. The children attended the Indian school, which was one of the first schools in Rhode Island. It was located on the shore of School House Pond.”7Princess Red Wing. Indians of Southern New England in Reflections of Charlestown 1876-1976, A memorial to the Bicentennial celebration of the United States of America. p128-146; quote p130. 1977

Individual Native landowners received titles or deeds for their land. Lands that were once tribal lands not subjected to property taxes now became taxable under individual ownership.

Another strategy in land dispossession was the application of what is now known as the Dawes Allotment Act of 1887, mentioned earlier.8See the Britannica entry on the Dawes General Allotment Act for more information. [link]

Though this particular strategy did not directly impact Rhode Island since the Narragansett were already detribalized when it was enforced, it demonstrated the continuation of the loss of Indigenous lands throughout the United States during this time period. Passed at a time when White American settlers expanded into the western parts of the United States, this Act put large tracts of land into the possession of “heads of household” in the case of families. Single adult males received a smaller tract of land. It then made “Indians” United States citizens and required them to follow federal, state, and local laws. The Act also allowed for remaining lands not allocated to be sold to the public at large. This was an aggressive strategy of land dispossession that later led many Natives to relocate to urban areas. Termination policies, which ended the federal government’s recognition of the sovereignty of tribes, spanned many years and led to further erasure of the Indian population. The Dawes Act was not used in Rhode Island because detribalization had already taken place and removed us from our lands. The effects in other parts of the country were nevertheless the same.

Things changed in 1934 when the Narragansett, along with many other tribal nations, were able to take advantage of the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). This Act passed by Congress was also known as the Indian New Deal and attempted to reverse earlier policies that denied Native Americans collective rights, as mentioned above. The aim of the Act was to strengthen tribes, reduce land dispossession, re-establish self-government, sovereignty, self-determination, and economic self-sufficiency. The Act also counteracted effects of assimilation and led to Native peoples being able to practice cultural norms and values. In essence, the act gave tribes more control of their destiny.9For more information, visit the National Archives. [link]

The Narragansett Tribe incorporated under the IRA, and Princess Red Wing designed the seal. It is the symbol most recognized for the tribe today. Princess Red Wing stated, “Under the Wheeler-Howard Bill (IRA) stating Indian tribes must be organized to be recognized, the Narragansetts called a meeting.” … “We planned to get a state Charter. Several of the tribal members appeared at the state house in Providence and met Governor Theodore Francis Green who gave the group a charter which we all signed.” A state charter would be part of the process of correcting wrongs of detribalization by the state.10Charlestown Bicentennial Book Committee. Reflections of Charlestown 1876-1976, A memorial to the Bicentennial celebration of the United States of America. Charlestown Bicentennial Book Committee. 1976

The IRA led to a time of renewed activity within the tribal community and the formation of many organizations and groups including the Sons and Daughters of the First Americans, the Women’s Society, and the Algonquin Council and Eastern Federation of American Indians. There were also less formal athletic clubs, historical societies, and youth and church groups.

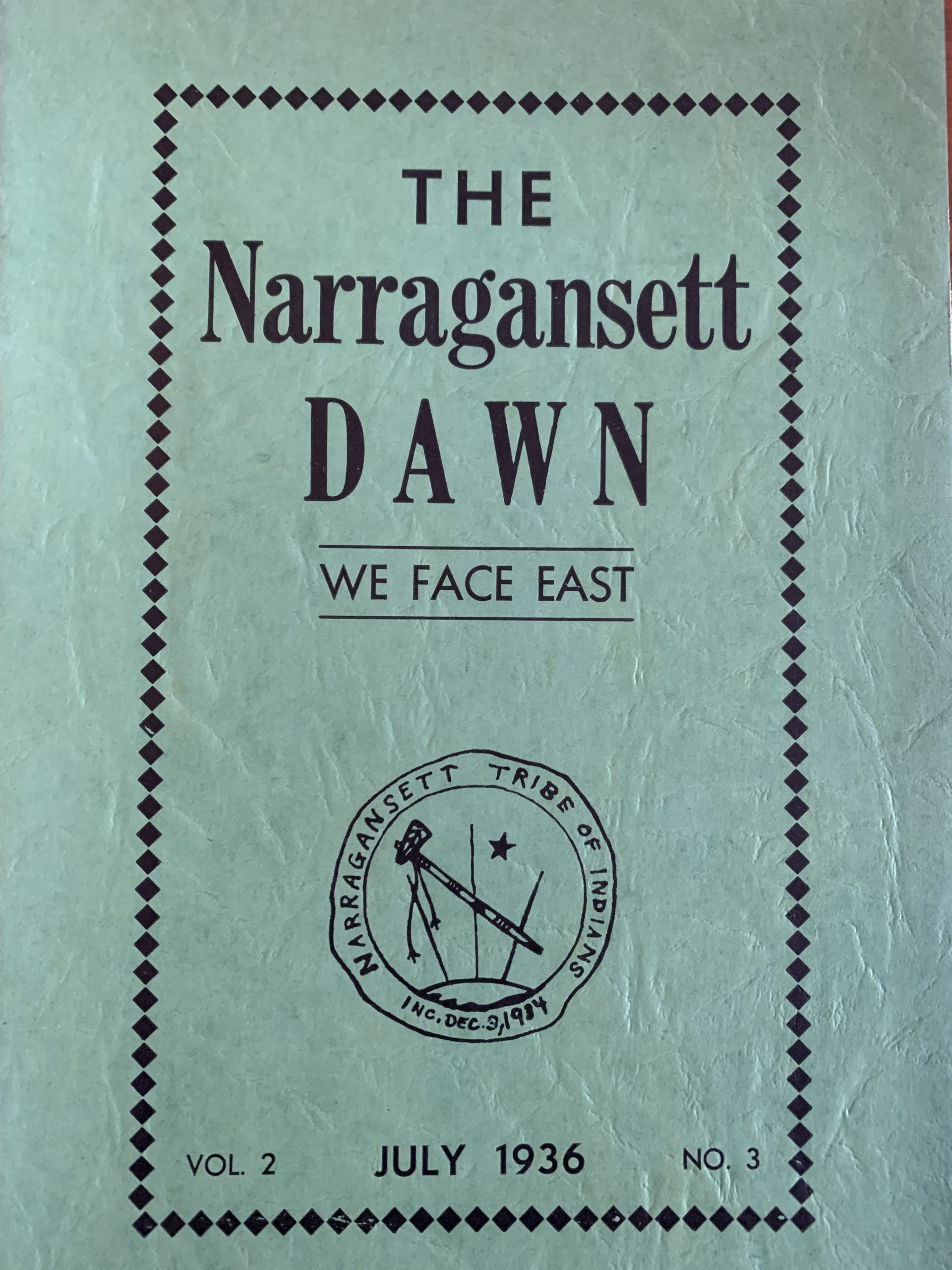

Tribal leadership continued ceremonies, developed new leaders, and took political actions such as marches, letter campaigns, and protests. They utilized their education to provide opportunities for their tribal community. The Narragansett Dawn, a news periodical, was created by a team of those with cultural knowledge, the first of its kind in this area. Princess Red Wing was the editor, and it included many contributing writers. Other tribal members wrote to document our history and culture, including Ella Brown Thomas (Seketau) who published Love Poems and Songs of the Narragansett. Walter Peek and Thomas Sanders published a book on American Indian Literature, and Princess Red Wing wrote a booklet, Indian Communications, which can now be found in the Tomaquag Museum archives.

Despite the IRA, termination policies continued and, in the 1950s, were used to remove the trust status between the United States federal government and tribal nations which protected communally held lands and gave federal resources to tribes. It was also used to force final assimilative policies on tribal citizens through urban relocation. The Bureau of Indian Affairs supported Native Americans who voluntarily relocated with housing and employment. However, many suffered greatly once they relocated to urban centers like New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, as they struggled with low-paying jobs, unemployment, poverty, homesickness, homelessness, discrimination, loss of community, identity, hopelessness, and loss of kinship support systems. They often went back to the reservation but were now disconnected from the way of life there. Today, we think of this as another form of identity erasure. It was a strategy used nationwide. The urbanization of Rhode Island impacted the tribal community as they tried to survive detribalization, displacement, urbanization, and educational assimilation.

The Narragansett Tribe continued its annual August Meeting, now called a Pow Wow, next to the Indian Church. Church services also continued. Along with the re-establishment of the political structure of the tribal government with Chief and Council, the tribe continued its kinship relationships throughout the hundred years of detribalization. We were still here and had continuation of familial ties. We were still socially, economically, politically, and culturally connected as a community. Our community was providing for itself through family businesses that included masonry, carpentry, and fishing, to name a few. We were also passing down our traditional arts, cultural knowledge, language, and lifeways. It is important to remember the notion of “we were still here” given that earlier scholars wrote about Native Americans as if they were vanishing, as noted earlier in this essay. The IRA had to be reinforced with subsequent legislation such as the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act and the 1978 Indian Religious Freedom Act. To this day, we still fight for the enforcement of these rights.

On July 29, 1982, the Department of Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs acknowledged the Narragansett Tribe as a federally recognized tribe with a nation-to-nation relationship with the United States and, as such, was entitled to all the privileges and immunities of all other federally recognized tribal nations. It took approximately one hundred years to right the wrong of forced detribalization by the state of Rhode Island. Federal recognition is an important part of self-determination, self-governance, and community wellness. Federal recognition helped us to create programs that support our community with educational opportunities, including a daycare center, youth programs, higher education and adult vocational training, a health center, police department, social services, ICWA child and family services, an historic preservation office, natural resources department, recreation areas, and the support for tribal government. The community continues to pass down cultural knowledge, history, arts, ecological, medicinal, and spiritual knowledge and practices. Though we would do so with or without federal recognition, federal recognition acknowledges the Narragansett as a nation.

Terms:

Colonization: the act of settling and gaining control over an area and the peoples that already occupy that area

Conquest: taking control over a place and subjugating the people in that place by force, usually through military force

Detribalization: remove a whole community from their social and political/governmental structure

Federal Acknowledgement / Recognition: the United States government recognizes an Indian tribe to exist as a sovereign nation. The United States government has a nation to nation relationship with federally recognized Indian tribes. There are exists Native American groups that are not recognized by the United States government.

Dispossession: taking away land, property, or other possessions

Genocide: the killing or decimation of a population of people usually belonging to a particular ethnic group or nation

Assimilation: becoming a part of a society. Taking in the customs, language, and norms of a society or country within which one lives but did not grow up

Blood quantum: defining someone’s identity based on the percentage Indian blood determined by genealogy or speculative measurement (which was estimated by researchers). In this case, Native Americans have to prove they have a certain percentage of Native American heritage to be able to claim certain rights under the government. This percentage has changed based on governmental policy

Propaganda: information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote or publicize a particular political cause or point of view

Christianization: converting a community to Christianity

Modernization: in this case, making Indigenous communities follow English customs that were considered modern at the time, such as in dress, food, clothing, language, and house structure

Westernization: similar to modernization, making Indigenous communities follow “western,” or Western European, customs and traditions

Termination policies: ending the relationship between the United States government and certain Native American tribes and nations, which resulted in loss of certain rights and sovereign status

Sovereignty: the ability for a community to control and maintain its own government. Federally recognized tribes are sovereign nations and have relationships with the United States government, much like states do

Trust: a “trust” relationship allows each nation, as a domestic sovereign, the right to self-determination, self-regulation, economic development, and self-governance

Pow Wow: a Native American tribal gathering originating from traditional thanksgiving ceremonies; they include ceremony, drumming, dance, traditional & contemporary foods, and traditional & contemporary arts vendors

Indian Child Welfare Act: this act gave tribal governments jurisdiction over the placement and welfare of Native American children in foster and adoptive homes. This act is to ensure Native American children on a reservation are not removed from their reservation, their community, and their culture

Indian Religious Freedom Act: this act gives Native American groups access to sacred sites, the right to use and possess sacred objects, and the right to worship through traditional ceremonies

Questions:

Why is gaining federal recognition important for a Native American group or nation? What rights does recognition help the Native community gain?

Why did the federal government need to pass acts to ensure Native Americans could claim certain rights? What rights were taken away from Indigenous peoples early on in the colonial period and during the early formation of the United States?

In what ways does the early loss of certain civil rights for Indigenous groups in this country still affect communities today? How can something that happened so long ago still have after affects to this day?

- 1Williams, Roger. “Chapter 22” in A Key into the Language of America, edited by Dawn Dove, Dorothy Herman Papp, Sandra Robinson, Lorén Spears, and Kathleen Bragdon, The Tomaquag Museum ed., 119. Westholme Publishing, 2019.

- 2See “Will current blood quantum membership requirements make American Indians extinct?” from the National Museum of the American Indian for more information. [link]

- 3

- 4Jean M.O’Brien, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence. University of Minnesota Press. 2010

- 5Narragansett Dawn , April 1936, p282-284. [link]

- 6See the main essay of this module for more information about the movement to Brothertown. [link]

- 7Princess Red Wing. Indians of Southern New England in Reflections of Charlestown 1876-1976, A memorial to the Bicentennial celebration of the United States of America. p128-146; quote p130. 1977

- 8See the Britannica entry on the Dawes General Allotment Act for more information. [link]

- 9For more information, visit the National Archives. [link]

- 10Charlestown Bicentennial Book Committee. Reflections of Charlestown 1876-1976, A memorial to the Bicentennial celebration of the United States of America. Charlestown Bicentennial Book Committee. 1976