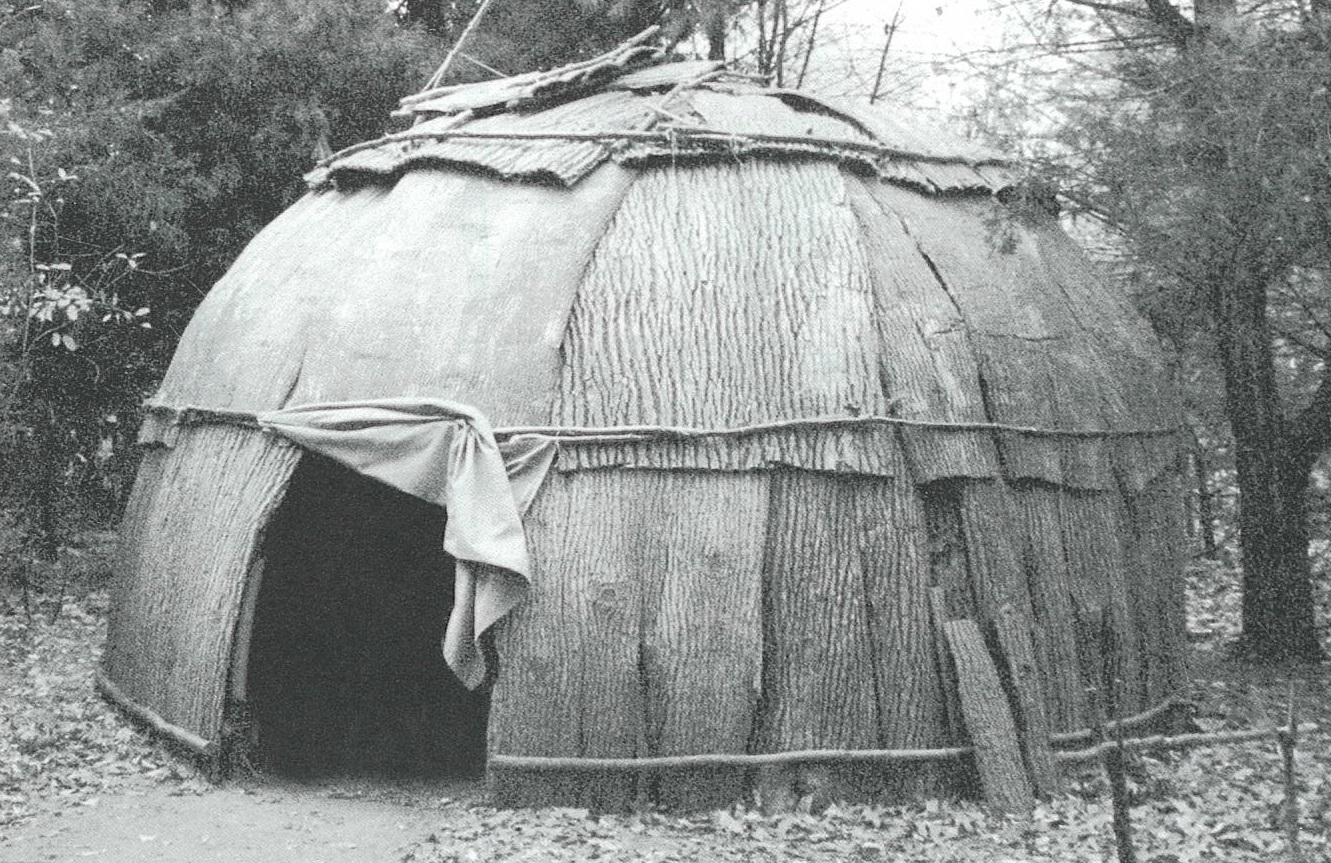

Wetu

This wetu was constructed by an Indigenous man in the mid-2000s for the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology’s educational programs in Bristol, RI. Visitors to the Museum learned about the lifeways of the people of the past. (The property in Bristol is no longer open to the public). Some of today’s Indigenous people have learned traditional techniques or methods for building and making tools and clothing that their ancestors did. In some cases, artists make traditional materials to educate other members of their group or those outside of their group about their cultural traditions, such as the wetu pictured here. In other cases, artists make traditional materials or modify traditional techniques to create aesthetic and meaningful art pieces such as a painting or decorative clay pot.

Indigenous Homes

By Pınar Durgun, Visiting Assistant Professor, Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, Brown University

The archaeological record suggests that the early Native American population in New England lived in different parts of the region for different purposes at different times of the year, mostly in scattered villages. There is not much evidence for large permanent settlements in this area, except at one site called RI 110, which is located northeast of Point Judith Pond. Here, archaeologists discovered evidence for about 20 structures that could have been “houses” that dated to before the arrival of the Europeans. These structures varied in shape and size, and the interior of the largest was 70 square meters. This large structure most likely served a communal function where people would gather for different purposes like ceremonies or meetings. Archaeologists estimate that approximately 60 people lived in this community, but the population could have been as high as 100 or 150. The community likely existed sometime between the 12th and 15th centuries. 1Derek Gomes, “Human Burial Site Found at Salt Pond,” The Independent, January 25, 2013. [link]2 “Late Woodland settlement and subsistence in southern New England revisited: The Evidence from Coastal Rhode Island” by Joseph N. Waller, Jr. North American Archaeologist 21/2: 139-153, 2000.

The lack of similar large, long-term settlements in other parts of Rhode Island could be due to what has survived in the archaeological record, not because Native New Englanders didn’t live that way. For example, some archaeological sites are not deeply buried and are close to the topsoil. This makes them vulnerable to later plowing, erosion, construction, and other modern human activities that would destroy the evidence at these sites.

Even if a site has been well preserved, an archaeological site never represents the full picture of how people lived because only the things left by people’s activities are what remains for archaeologists to piece together. Many organic remains that were a big part of Native Peoples’ lives such as foods, drinks, animal fur, woven mats, blankets, fishing nets, baskets, plants and wood, will decay, disintegrate, or disappear after hundreds of years, especially when they are in wet and humid areas like Rhode Island is. What remains are objects made of inorganic materials like stone, pottery, and metals. Therefore, some elements of ancient lives are harder to reconstruct or understand than others.

Ancient New England peoples were inclined to frequently move their dwellings from place to place, which makes it harder for archaeologists to locate the sites. For some groups, the size and shape of dwellings would change, depending on population density and the time of year. In southern New England, ordinarily, a family lived in its own separate dwelling in the summer. Two or more families might combine to occupy a larger structure in the winter, each having their own fire and quarters. 3Indian New England 1524-1674: A Compendium of Eyewitness Accounts of Native American Life, Edited by Ronald Dale Karr, 1999. 4 “‘Towns They Have None’: Diverse Subsistence and Settlement Strategies in Native New England”, Elizabeth Chilton, in Northeast Subsistence-Settlement Change: A.D. 700–1300 by John P. Hart and Christina B. Rieth. New York State Museum, 2002.

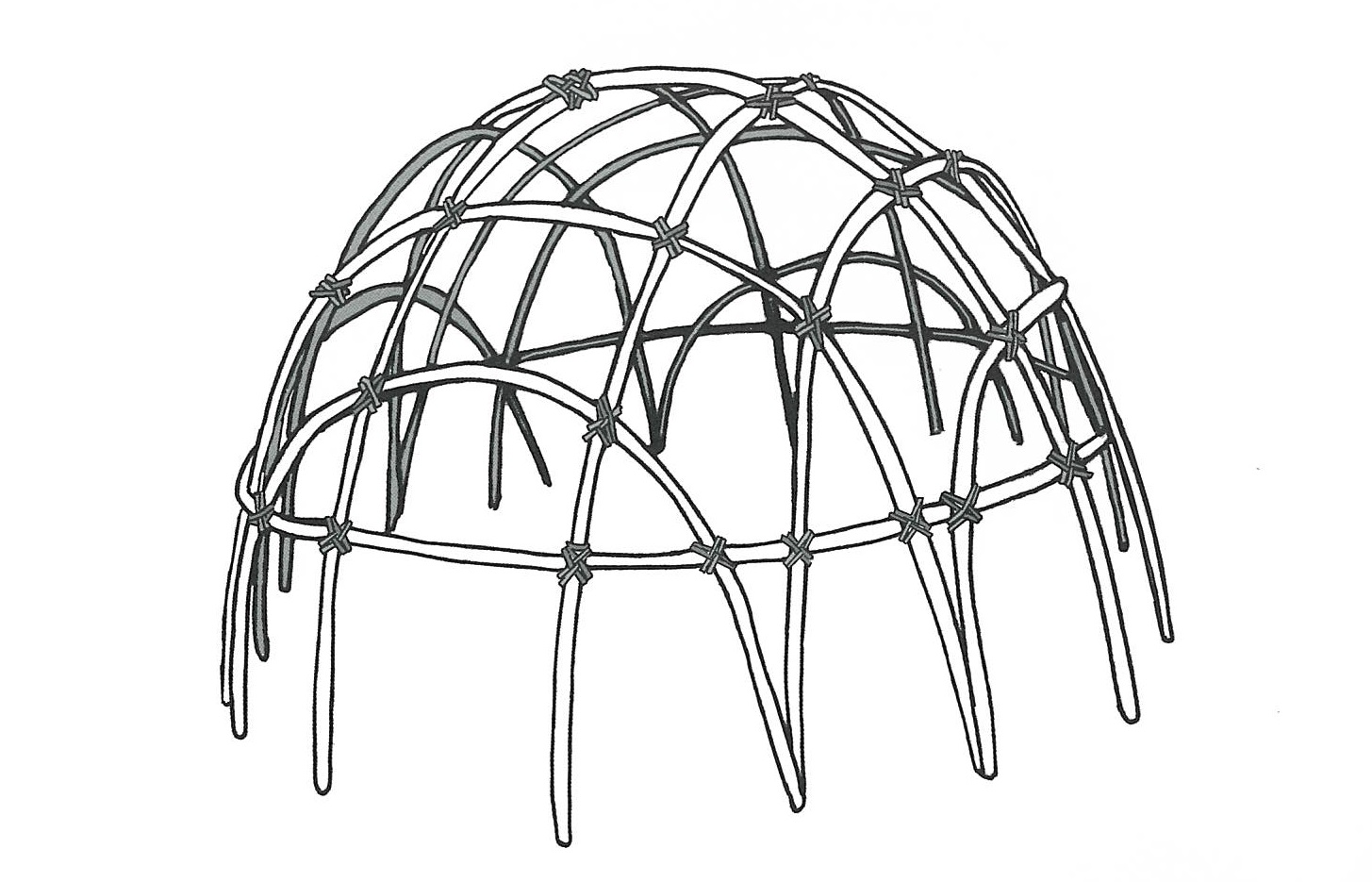

The New England Native home, the wetu , was relatively easy to construct. They had vertical sides and were either round or oblong. They were built with small poles fixed in the ground, bent and fastened together with cord. The base pole structure would be covered with reeds, bark, or mats. A smoke-hole would be left at the top to allow the smoke from the inside fire to vent up and out. Today, you can see a reconstruction of a Native New England house at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum, Harvard University’s Peabody Museum, or at the Native village at Plimoth Plantation.

Archaeologists can tell where people cooked their food by looking at charcoal remains, or where they set up their wetus by looking at the discolored circles in the soil left after the home’s wooden poles decomposed. They might find shells and animal bones nearby and infer that the people ate those animals like deer, turkey, clams, oysters, and scallops. Sometimes shells and bones were made into objects such as tools for hunting, sewing, preparing food, or made into jewelry. So far, archaeologists have not recovered a full wetu, but they have found sites like the Joyner site at Jamestown with various human activities, and traces of the circular postholes that indicate there once was a settlement. 5Native American Archaeology in Rhode Island, RI Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission, 2002: 53.

The Narragansett, Niantic, and Wampanoag peoples were still making and living in wetus when the Europeans first came to Rhode Island. Many of their descendants still make wetus today to remember the traditional technology of their ancestors, to continue to teach that technical knowledge to their children, and to teach non-Native Americans about how they lived in the past. Because the technology of making houses and other tools is still being done today, archaeologists can use that knowledge to help them understand the fragmented evidence they find in ancient sites.

Terms:

Preserved: materials that are in, or close to, their original state.

Organic: materials made from animal or plant such as bone tools, fur blankets, and reed mats, that will more likely not preserve well, or at all, over time depending on the conditions or climate. Organic materials may last longer if buried in sand in the dry desert, or if encased in ice, but not in wet, acidic soil like we have in Rhode Island.

Inorganic: materials made that are not made from plant or animal such as clay, stone, and metal that will more likely stay preserved over time.

Wetu: the Narragansett word for “house.” Some references refer to this home structure as a wigwam. Note: scholars often italicize words that come from languages other than English.

Questions:

What kinds of evidence do archaeologists find at sites? What do those kinds of evidence tell us about how people lived in the past?

What are organic materials? What happens to them over time?

How do today’s Native Americans help archaeologists understand what they find at ancient archaeological sites?

- 1Derek Gomes, “Human Burial Site Found at Salt Pond,” The Independent, January 25, 2013. [link]

- 2“Late Woodland settlement and subsistence in southern New England revisited: The Evidence from Coastal Rhode Island” by Joseph N. Waller, Jr. North American Archaeologist 21/2: 139-153, 2000.

- 3Indian New England 1524-1674: A Compendium of Eyewitness Accounts of Native American Life, Edited by Ronald Dale Karr, 1999.

- 4“‘Towns They Have None’: Diverse Subsistence and Settlement Strategies in Native New England”, Elizabeth Chilton, in Northeast Subsistence-Settlement Change: A.D. 700–1300 by John P. Hart and Christina B. Rieth. New York State Museum, 2002.

- 5Native American Archaeology in Rhode Island, RI Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission, 2002: 53.