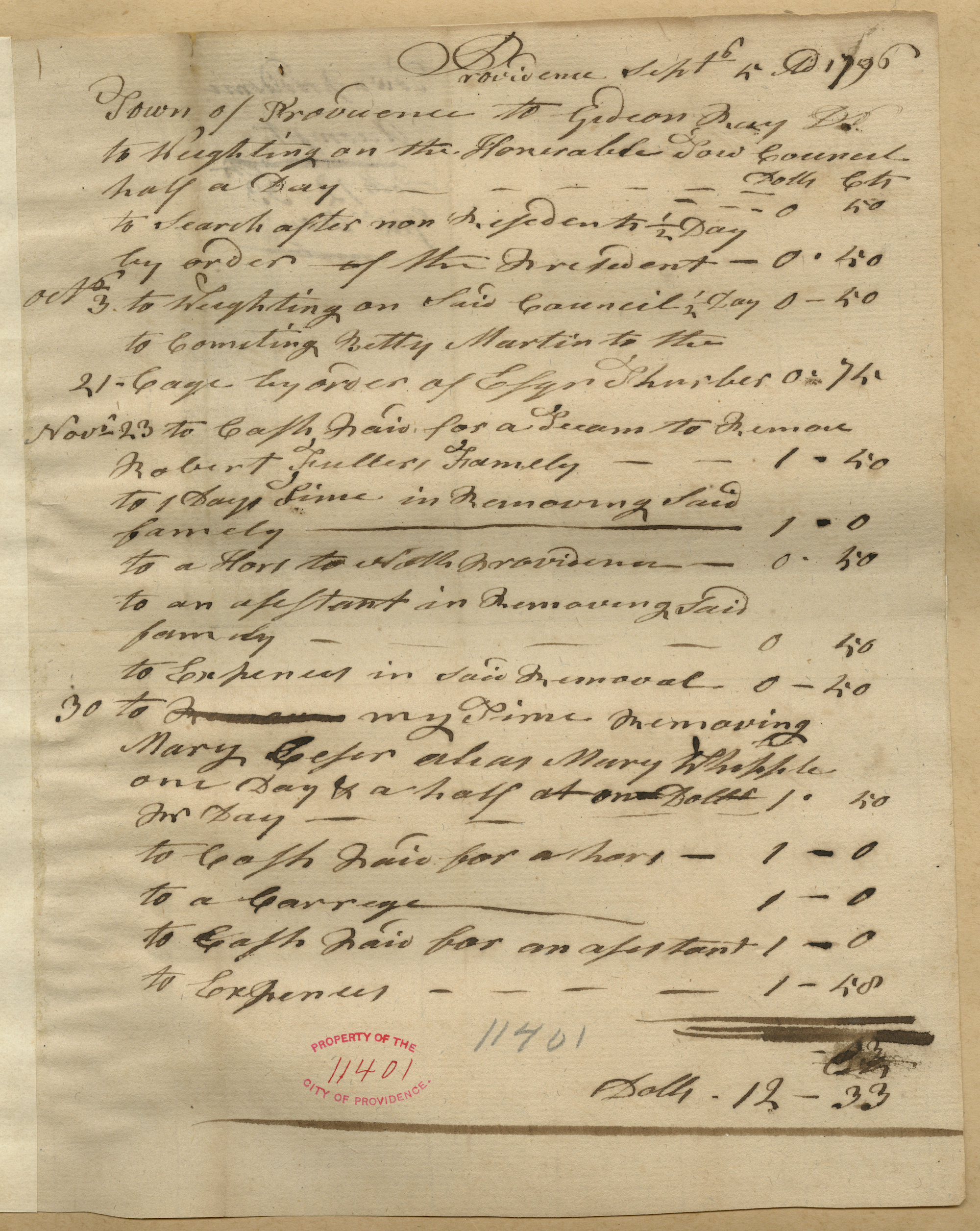

Payments for the Removal of Non-Citizens

This 1796 manuscript shows a list of payments by the Providence Town Council to individuals for their work removing individuals and families from the town, or “warning out.”

[Click here to see a full transcription of the document]

Citizenship in Providence, RI: the long road to rights

Essay by Traci Picard, public historian

Citizenship is a foundational civil right. It confers status upon an individual. It tells us, and everyone else in our community, that we “belong” in a place, both legally and socially. It also gives us access to the other civil rights conferred upon us, both federal rights, which come from the country we live in, and state rights, which come from the state we live in. And it confers these rights upon the next generation. Since Rhode Island was founded initially as a colony of England, many of our early laws were derived directly from British laws.1Winson, Gail I., “Researching the Laws of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations” (2003). Roger Williams University School of Law Faculty Papers. Paper 1. [link]

Before the concept of citizenship was created, there was settlement, which determined who had the right to settle in a town and to be a legal inhabitant. The 1662 Poor Relief Act described the process of acquiring settlement rights, saying, “if the person or persons shall not return to the place aforesaid when his or their work is finished or shall fall sick or impotent whilst he or they are in the said work it shall not bee accounted a Settlement.”2“Charles II, 1662: An Act for the better Releife of the Poore of this Kingdom.,” in Statutes of the Realm: Volume 5, 1628-80, ed. John Raithby (s.l: Great Britain Record Commission, 1819), 401-405. British History Online, accessed July 10, 2020 [link] In other words, workers who traveled were welcome to enter a town to work, but they were not the financial responsibility of the town if something bad happened, and they would eventually need to move on. The policy acknowledged the town’s need for workers, while also did not welcome them to settle in the community as residents.

How was a person able to legally settle in Rhode Island? Property ownership was a major factor in determining citizenship. White men who owned any property were given the “right of settlement” in the town. Through this, they received the ability to vote, to hold office and to help shape the policies that governed their town and colony. Over time, the policies of each location evolved from this foundation. These policies were adopted through town councils and enforced by the prominent property owners who made judgments in the town’s court, often to their own advantage.

One of these policies was determining who did not belong in their town. Citing their concern over paying for the care of poor residents, the prominent property owners acted as lawmakers to craft policies that blocked unwanted residents from legally settling. They set out requirements for residency and decided who was “deserving” of relief in the form of food, shelter, or money from the town. Relief was available only to those deemed deserving by the town councils and came with expectations regarding behavior, work and family structure. The town leaders were most likely to welcome in people who had family or business connections to those already settled. They also favored workers with skills in high demand and migrants with significant financial resources. The stated reasoning for these rules was the cost of providing poor relief. Yet, it was not applied equally to the residents of the town.

“The first line of relief for the poor was the family,” says historian William P. Quigley, “and the statute provided a three-generation, mutual, and legally enforceable obligation to care for family members in need.”3Quigley, William P., Reluctant Charity: Poor Laws in the Original Thirteen States (June 19, 1997). 31 U. Rich. L. Rev. 111 (1997); Loyola University New Orleans College of Law Research Paper If a family was unable to support their injured, ill, or struggling member fully, the town contributed money or goods to their care. Hospitals were only utilized for extreme cases, and most care happened in private homes. This worked for many families. Yet, there were several key reasons why some were unable to use this system. Slavery and the structure of White supremacy tore apart Black families through laws, economic practices, and violence. In the late 1700s, many enslaved people became free due to veteran status4Following the American Revolution, African American men who served in the Rhode Island First Regiment and other segregated, all-black units were made free in exchange for their military service, an explosion of moral and religious arguments concerning the inhumanity of slavery and bondage, and the 1784 Gradual Emancipation Act.5An Act for the gradual abolition of slavery, 1784. Rhode Island State Archives. Accessed July 1, 2020 [link] In addition, hundreds of the enslaved use the opportunity of war to flee.6Manisha Sinha. The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition. Yale University Press. 2017 But freedom from enslavement did not mean freedom from restrictions on social and geographic mobility. Historian Christy Clark Pujara tells us, “The actions of white citizens and administrators directly contributed to the poverty of newly freed people.” 7Clark-Pujara, Christy Mikel. Slavery, emancipation and Black freedom in Rhode Island, 1652-1842. PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) thesis, University of Iowa, 2009

Many of the same inequitable rules that were created to support and justify slavery, as well as social norms that blocked access to education and upheld segregation, affected free Black people. Although free, they faced a history of being legally categorized as “property” during enslavement, and this category denied legal personhood and created great inequity. Poverty, illness, and forced migration disrupted the families of free Black people, Indigenous people, and poor White people, too. Rhode Island’s earliest settlements were also major seaports, where many worked as sailors and even more worked in the wider maritime industry, building and repairing boats, provisioning ships, and providing services to the seafaring population.8Martha S. Putney. Black Sailors: Afro-American Merchant Seamen and Whalemen Prior to the Civil War. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 1987 This industry attracted working-class men, both Black and White, who had few alternatives. It was a dangerous life and required them to be away from home for long stretches of time. Without an intact family as a safety net, those in need often had to create alternative networks to survive. These networks provided a community for marginalized people, but they faced the constant threat of disruption. Often located in neighborhoods on the edges of the town or city, we can look at places like Providence’s Snowtown, Hardscrabble, and Stamper’s neighborhoods as sites of resilience, survival, and cultural creativity. They were also sites of ongoing social battles.

One of the regular disruptions to these communities was the system of “warning out”. Warning out was a system of determining who could legally settle in a town. Any person could be called before the Town Council to be examined and questioned about their residency status. Often, they were called to testify due to a complaint from a “respectable” resident of the town. This complaint might say that the person was seen in “bad company,” had a child out of wedlock, encouraged enslaved or indentured women to rebel against the system, or conducted themselves too loudly. These complaints help us to understand the restrictive nature of life for the poor, especially poor people of color (African Americans, Indigenous) in the early 19th century. The examined person would be questioned thoroughly, and sometimes invasively, by a panel of White men. After the Revolutionary War, Rhode Island cities and towns levied high taxes to make up for considerable war costs. Rhode Islanders, particularly those who were formerly enslaved, found themselves in dire financial strains due to the heavy taxes. “At a time when many of the middling sort could visualize themselves falling into ruin from three thick layers of taxation [town, state, and federal levels], they were not inclined to be generous to those already in poverty.”9Ruth Wallace Herndon. Unwelcome Americans: Living on the Margin in Early New England. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2001. p2 This meant that cities and towns did not want to take on the burden of aiding those in need and instead used this system of warning out to prevent having to take responsibility for them.

Records show us that society was highly stratified at that time, and women gained status through familial or marriage linkages with men. Many of the records of these examinations have survived and can give us insight into the lives of the inhabitants denied legal settlement:

Mary Ceasar, for example, was a Black woman who lived in Providence. She was called in front of the Council for examination “for being reported to this council as a person of bad fame” in 1801. She was born to Sarah Olney and Ceaser (full name unknown) in Smithfield, RI, and came to Providence in 1792. She “kept house and lived in a tenement of Governor Fenner’s where she sells cakes,” and although she did not sell liquor in the house, “her company frequently sends abroad for liquor which they drink at her house.” She “keeps [lives with] with Anthony Brown[ing],” but they were not considered legally married by the Council. This woman, who was living in a home owned by the Governor for seven years and selling cakes to support herself, was rejected from living in Providence, her home of nine years. She was judged by the council to “belong to” the town of Smithfield, where she was born. They examined her partner Anthony, who had bought his freedom from enslaver Wilkinson Brownell of South Kingston. Anthony worked as a laborer and a peddler in Providence for eight years but was rejected from becoming a legal inhabitant and sent back to South Kingstown, the home of his former enslaver.10Record 8:75, Providence City Archives. Providence Town Council. “Providence Town Council Records Book,” 1801. 1789-1801 [8:75]. Providence City Archives

Luthania Bates, “alias Lealand,” was first examined by the Providence Town Council in 1792. Presumably White, she was born to Jesse Lealand and an unnamed mother in Johnston. Mr. Lealand then purchased property in Attleboro, MA. Luthania was married there to property owner Reuben Bates, whom she divorced in 1791. Divorce was unusual at that time, and her actions signaled to the Town Council that she did not feel the need to adhere to traditions or conventions. The Town Council rejected her from being an inhabitant of Providence and ordered her back to Attleboro. In 1801, Luthania was examined in Providence again. She was living in the North end of Providence near Charles St., and was the subject of a complaint from Amos Atwell. He told the council that Luthania “entices away the female help of many of the good Citizens of this Town and harbours them to the great injury of themselves and their employers, whereby the peace and good Order of the Inhabitants thereof is in a great measure interrupted and destroyed.” In a society where women faced very rigid expectations and rules, it was unusual to see a woman offer alternatives to these rules. Female obedience was important to maintaining order. In one sentence, we can see how Luthania was challenging the intersecting systems of patriarchy, race, and class all at the same time. She was rejected from Providence again.11Record 8:28, Providence City Archives. Providence Town Council. “Providence Town Council Records Book,” 1801. 1789-1801 [8:28]. Providence City Archives

Phillis Wanton was a Black woman born in Attleboro, MA. She was enslaved by a man named Mr. Saunderson, who decided to return to England and “gave” Phillis to John Merritt, who then died. Merrit’s family sold her to Boston brickmaker John Field, who then sold her to a Mr. Peck. Around the time of The Blockade of 1775, Peck told Phillis to leave “to seek and provide for herself.” The Blockade was part of the Boston Port Act, which blocked off the port of Boston and shut down commerce coming in or out.12Fremont-Barnes, Gregory, ed. The Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies: 1760-1815. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007 This disrupted the businesses and lives of many who lived in the Boston area and caused some people to leave the area due to fears and tensions that soon led to the Revolutionary War. Amidst this difficult political climate, she fled Boston to Providence, and ended up living in the home of Moses Brown, by that time an abolitionist. She married a man named Jack Wanton, who was born in Africa and lived in Newport. Jack had been manumitted by John Wanton in 1791. Phillis was called before the Providence Town Council in October of 1800, and she stated that her husband was “at times insane.” Two of her children, Squire and Mariane, were “bound out” in Foster and the youngest, Vina, lived with Phillis. Although Phillis clearly wanted to live in Providence, the Town Council rejected her at least two separate times from making her home there and ordered her removed to Newport. The Council reports that Newport is the family’s legal settlement, although we can see that it is only so because Jack Wanton was enslaved there for 15 years. Phillis Wanton’s experience is illustrative of the ways that White men exerted power over the lives of Black women, controlling where they could live and moving them from place to place with no concern for what this meant to the women themselves.13Record 7:549, Providence City Archives. Providence Town Council. “Providence Town Council Records Book,” 1800. 1789-1801 [7:549]. Providence City Archives

Based on current research, it appears the practice of warning out had ended by the 20th century. Towns turned into cities, grew exponentially through an increase in industrialization and immigration, and strict control over who belonged was no longer as feasible. Asylums, poorhouses, and workhouses also emerged as an alternative to removing unwanted inhabitants. Those who could not provide for themselves were institutionalized rather than being removed. In most cases, people committed to such places were required to perform work in exchange for their room and board. “Transients did not have legal inhabitant status,” says Ruth Wallis Herndon, “but they provided essential labor for those who did.”14Herndon, Ruth Wallis. Unwelcome Americans Living on the Margin in Early New England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010

The effects of this system continued even after the end of the warning-out system. Providence resident Thomas Howland was denied a United States passport as late as 1857, and the US Customs official in charge told him, “Passports are not issued to persons of African extraction. Such persons are not deemed citizens of the United States.”15Hammerstrom, Kristen. “Faith & Freedom Friday: Thomas Howland.” A Lively Experiment, February 2, 2018. [link] On a federal scale, concurrent with this statement, was the Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford. Enslaved Missouri man Dred Scott sued his enslaver for freedom, and it went all the way to the highest court, where a complex situation of competing ideas played out. It was ruled in 1857 that Black persons did not have equal rights under the Constitution because they were not legally citizens of the United States.16Finkelman, Paul. Dred Scott v. Sandford: a Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2017 This story points us toward how the foundational civil right of citizenship grants the rights that Americans are promised today. When we better understand how citizenship has been applied in the past, we can see the challenges faced by marginalized residents throughout history and the ways that the concept of citizenship was used to punish or reward people for adhering to an ideal deemed “respectable” by prominent, property-owning White men.

Terms:

Citizenship: legal recognition that a person belongs to a town, county, state, or nation and has certain rights because of that status

Settlement: a term referring to a person’s legal place of residence. Certain rights are given to those deemed a resident of a place

Gradual Emancipation Act of 1784: according to this act, children born to enslaved people would not remain enslaved and masters could manumit healthy enslaved people between the ages of 21 and 40 without assuming financial responsibility. It was meant to slowly phase out slavery.

Inequitable / Inequity: an unequal distribution of power, resources, or rights

Personhood: a term referring to the status of being a legal person with a set of rights

Forced migration: being forced to move from one place to another against one’s will, usually under threat of violence

Maritime: related to the sea

Marginalized: a person or group with less access to power, decision-making and influence. That person or group may also be forced into homes and jobs that are less desirable or more dangerous

Stratified: a hierarchical system where social and economic differences between classes are significant

Patriarchy: a form of government or a society in which men are given more power than women

Manumit: legally releasing an enslaved person from the condition of slavery and giving up all claims to their time, labor and confinement

Bound out: entering a contract where one person agrees to work for another for a set amount of time in exchange for something like room and board or job training. Also called indentured servitude. Children could be bound out by their parents if they could not afford to take care of them

Transient: a person who has no permanent address and may move from place to place

Questions:

Why do you think the Town Council consisted of property-owning white men? What do you think it meant for them to hold all of the power over the citizenship of others?

Many quotes in this essay discuss the link between laboring (working) in a place and living in a place. Why do you think Town Councils allowed certain people to work in their town but not live there? What are they gaining through that decision?

Where do we see tension around citizenship between citizens and governments today? Do you see similarities between these modern issues and the historic ones highlighted in this essay?

- 1Winson, Gail I., “Researching the Laws of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations” (2003). Roger Williams University School of Law Faculty Papers. Paper 1. [link]

- 2“Charles II, 1662: An Act for the better Releife of the Poore of this Kingdom.,” in Statutes of the Realm: Volume 5, 1628-80, ed. John Raithby (s.l: Great Britain Record Commission, 1819), 401-405. British History Online, accessed July 10, 2020 [link]

- 3Quigley, William P., Reluctant Charity: Poor Laws in the Original Thirteen States (June 19, 1997). 31 U. Rich. L. Rev. 111 (1997); Loyola University New Orleans College of Law Research Paper

- 4Following the American Revolution, African American men who served in the Rhode Island First Regiment and other segregated, all-black units were made free in exchange for their military service

- 5An Act for the gradual abolition of slavery, 1784. Rhode Island State Archives. Accessed July 1, 2020 [link]

- 6Manisha Sinha. The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition. Yale University Press. 2017

- 7Clark-Pujara, Christy Mikel. Slavery, emancipation and Black freedom in Rhode Island, 1652-1842. PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) thesis, University of Iowa, 2009

- 8Martha S. Putney. Black Sailors: Afro-American Merchant Seamen and Whalemen Prior to the Civil War. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 1987

- 9Ruth Wallace Herndon. Unwelcome Americans: Living on the Margin in Early New England. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2001. p2

- 10Record 8:75, Providence City Archives. Providence Town Council. “Providence Town Council Records Book,” 1801. 1789-1801 [8:75]. Providence City Archives

- 11Record 8:28, Providence City Archives. Providence Town Council. “Providence Town Council Records Book,” 1801. 1789-1801 [8:28]. Providence City Archives

- 12Fremont-Barnes, Gregory, ed. The Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies: 1760-1815. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007

- 13Record 7:549, Providence City Archives. Providence Town Council. “Providence Town Council Records Book,” 1800. 1789-1801 [7:549]. Providence City Archives

- 14Herndon, Ruth Wallis. Unwelcome Americans Living on the Margin in Early New England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010

- 15Hammerstrom, Kristen. “Faith & Freedom Friday: Thomas Howland.” A Lively Experiment, February 2, 2018. [link]

- 16Finkelman, Paul. Dred Scott v. Sandford: a Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2017